(First of two parts)

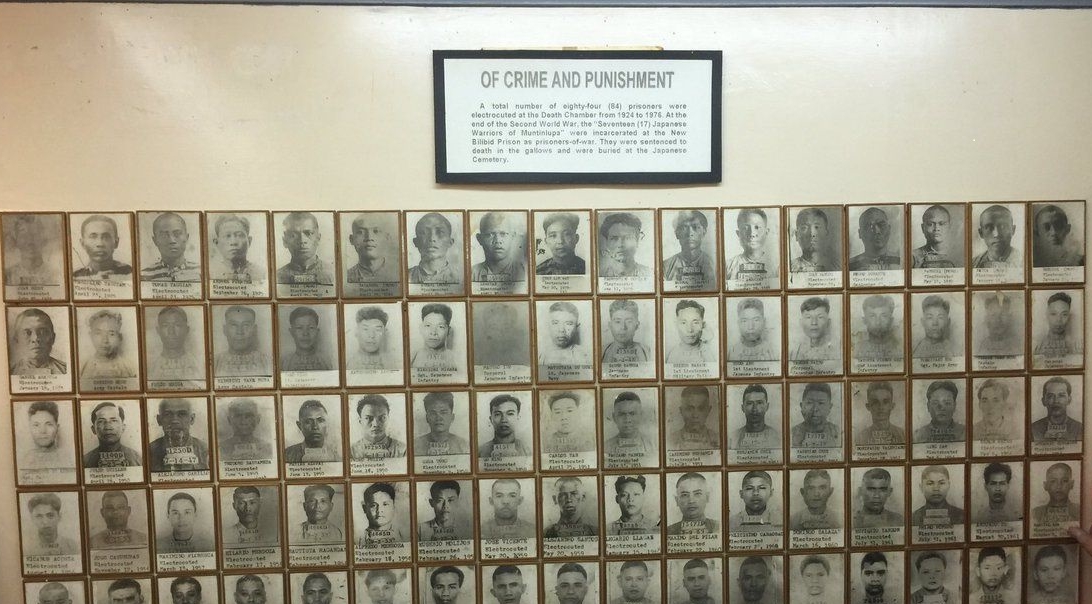

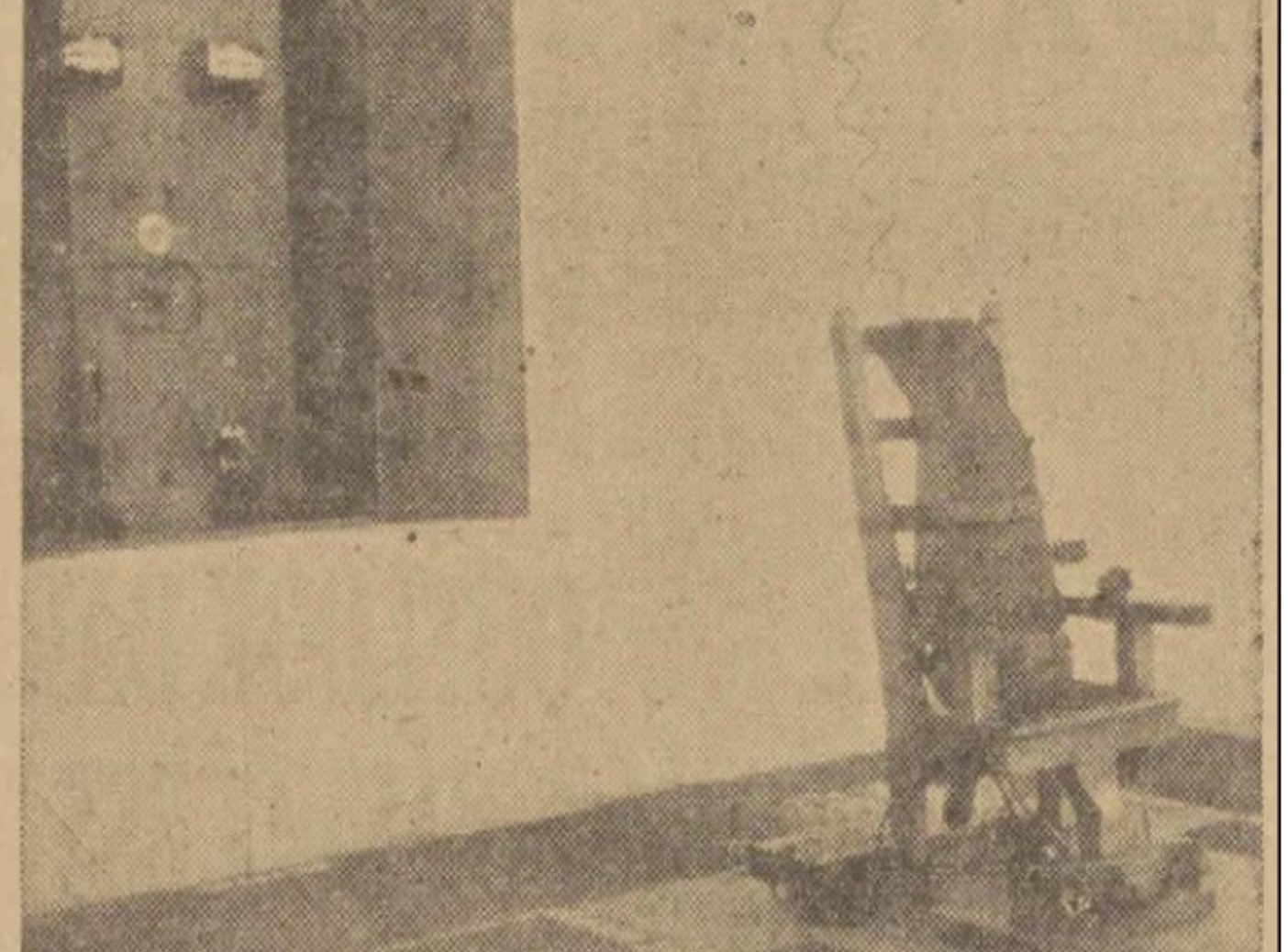

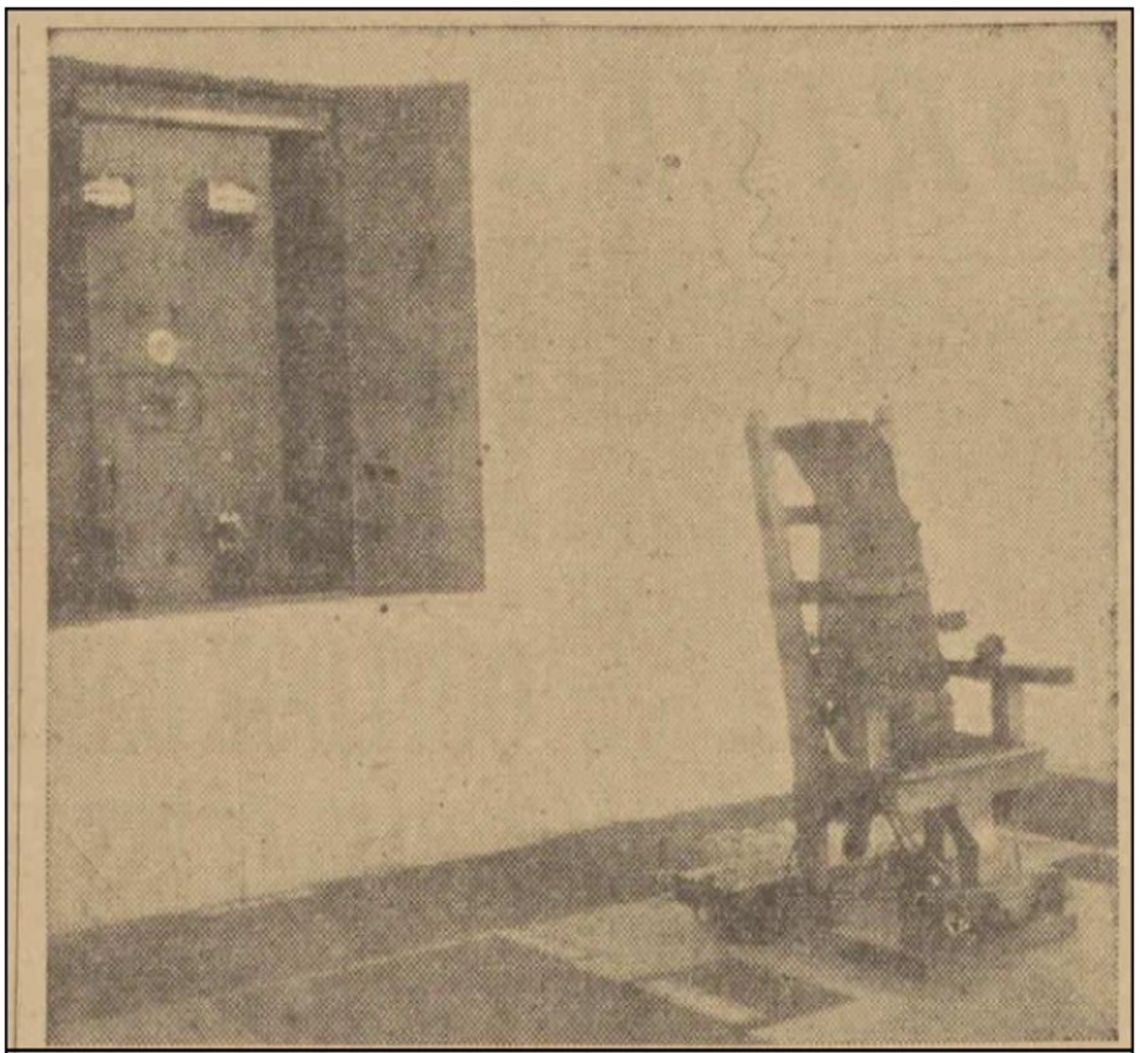

The electric chair in the Bilibid Prison in Manila was unused during Quezon’s presidency. Photo from Tribune, July 12, 1939.

A few minutes into his fourth State of the Nation Address (SONA) last

July 22, 2019, President Rodrigo Roa Duterte

asked Congress “to reinstate the death penalty for heinous crimes

related to drugs, as well as plunder.” It was the second SONA in

which Duterte asked Congress to reimpose capital punishment. In 2017,

he asked Congress “to act on all pending legislations to reimpose

the death penalty on heinous crimes.” He linked then the

restoration of the death penalty to his effort “to completely

eradicate the menace of illegal drugs, criminality and corruption.”

This year, Duterte used the 2017 Marawi siege as an example where

terrorism was supposedly fueled by the drug trade, by the “tons of

shabu worth millions and millions of pesos.” In President Duterte’s mind, “drug money killed 175 and wounded [2,101] of my soldiers and policemen in that five-month battle.” And the trade in illegal drugs “will not

be crushed unless we continue to eliminate corruption that allows

this social monster to survive” — hence his call for the

reinstatement of the death penalty only for heinous crimes related to

drugs and plunder.

Duterte is not the first president to have to asked Congress to bring back

the death penalty in two SONAs. Former president Fidel Valdez Ramos,

in his first SONA on July 27, 1992, asked Congress “to restore the

death penalty to cover heinous crimes, which of late have enjoyed a

resurgence — encouraged, no doubt, by the weakness of our

deterrents.” In his second SONA on July 26, 1993, Ramos reiterated:

“Last year, I proposed we restore the death penalty. I ask you to

enact that measure as soon as possible. We must show determination to

prevent any reversions to barbarism.”

Ramos was trying to take advantage of an opening in the 1987 Constitution.

Instead of writing into the Charter an absolute ban, the framers

ended up agreeing on the compromise position that “neither shall

death penalty be imposed, unless, for compelling reasons involving

heinous crimes, the Congress hereafter provides for it.”

On Dec. 13, 1993, Ramos signed into law RA 7569 imposing the death

penalty on certain heinous crimes. The law covered the following

crimes: treason, piracy and mutiny on the high seas or in the

Philippine waters, qualified bribery, parricide, murder with

aggravating circumstances, infanticide, kidnapping and serious

illegal detention, robbery with violence against or intimidation of

persons, destructive arson, rape with special circumstances, plunder,

and various offenses related to illegal drugs.

Thirteen years later, Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo abolished what Ramos desired,

signing into law on June 24, 2006 Republic Act 9346 that prohibits

the imposition of death penalty in the country. Prior to the

abolition of capital punishment, seven were executed through lethal

injection — three for rape, three for robbery with homicide, and

one for rape with homicide. All seven were executed during the

presidency of Joseph Ejercito Estrada.

The last execution was undertaken on January 4, 2000. In response to the

call of the Catholic Church to show mercy and compassion as it

celebrates its Jubilee Year, Estrada declared a moratorium on all

executions on March 24, 2000. A series of mass commutations followed.

On December 10, 2000, while facing an impeachment trial in the

Senate, Estrada ordered the commutation of death sentences of around

1,300 death row inmates. On December 26, 2000, and on January 4,

2001, he again ordered mass commutations that affected around 200

death convicts.

It is reasonable to interpret Estrada’s actions as calculated moves to

get the Catholic church on his side as he fought for his political

survival. It is also possible that he was trying to make things right

for the one life he lost to lethal injection. As reported by Seth

Mydans of the New York Times:

President

Joseph Estrada has remained ambivalent about the death penalty. In

Mr. [Eduardo] Agbayani’s case, when the president received a

final-hour plea for clemency from a prominent bishop, he acted

quickly. He picked up his home telephone and called the prison.

First, he got a busy signal, then a fax line. By the time an aide

called the prison on a hot line from the presidential palace, Mr.

Agbayani was dead.

With the reimposition of the death penalty in 1993, presidents from then

on had to learn to wield their enormous power over the life and death

of a convict. Article 7, Section 19 of the 1987 Constitution provides

that, “except in cases of impeachment, or as otherwise provided in

this Constitution, the President may grant reprieves, commutations

and pardons, and remit fines and forfeitures, after conviction by

final judgment.”

Save for the Philippine Organic Act of 1902 and the 1986 Freedom

Constitution, all other constitutions provided for a chief executive

that can pardon, grant reprieves, or commute sentences. The 1899

Malolos Constitution provided that the president can “pardon

lawbreakers in accordance to the law.” The Jones Law of 1916 vested

the governor-general “with the exclusive power to grant pardons and

reprieves.” The constitutions of 1935, 1943, 1973, and 1987 all

empowered the chief executive to “grant reprieves, commutations and

pardons.”

Will the president save a convict’s life? In the drama of executions,

that remains one of the main questions that observers keenly await an

answer to.

In the 1930s, the answer to whether the chief executive would save a

convict’s life was always yes. That decade can be viewed as the

exact opposite of our times when it comes to the national leadership

and its predisposition toward the death penalty.

When Frank Murphy assumed office as the last American governor general on

July 15, 1933, until the end of his term on Nov. 14, 1935, he

commuted sentences and issued reprieves to make sure that no convict

was executed. Conservative diplomat and historian Lewis E. Gleeck Jr.

described Murphy as having a “repugnance to capital punishment,”

who “set murderers free (in a country where political murders were

common) to murder again or encourage others to murder in the thought

that they could escape punishment.” Gleeck went on to assail Murphy

as “a dewy-eyed sentimentalist and … a knee-jerk liberal.”

Murphy ended his political career as an associate justice of the US

Supreme Court.

However, the use of executive clemency was not the preserve of weak-willed

men, as Gleeck implied. “The late Manuel L. Quezon has always been

associated in the public mind with resolute masculine authority … a

whip-cracking authoritarian with great executive force and drive …

Behind the stern facade was a record of compassion, a religious

sensitivity unmatched perhaps by any of his successors. Quezon …

did not allow any execution to take place under his administration,”

wrote the journalist Jesus V. Merritt in a Philippines Free Press

piece on July 30, 1960.

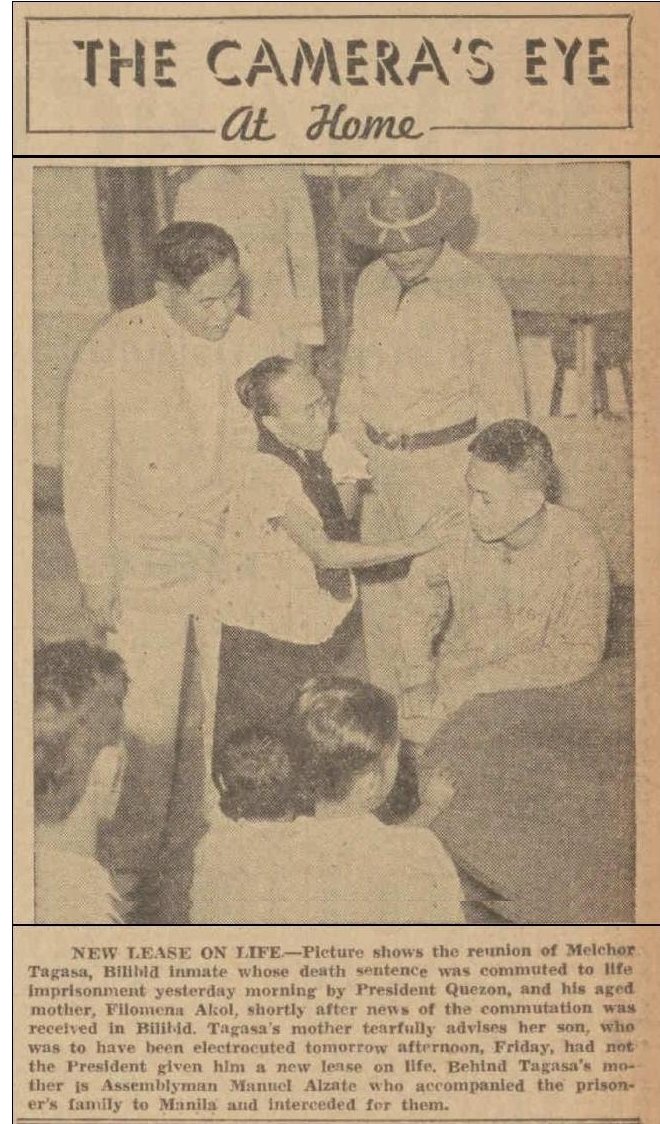

Melchor Tagasa

with his mother Filomena Akol as they were informed of President

Quezon’s commutation of his sentence from death to a life sentence.

Clipping from Tribune, July 27, 1939.

In Quezon’s own account, as quoted by Merritt, his opposition

to the death penalty was, in part, rooted in the story of an

execution: that of Jose Rizal. After he was inaugurated as

Commonwealth president on Nov. 15, 1935, he had this realization:

“I remembered the legend of the mother of Rizal, the great Filipino

martyr and hero, who went up those stairs on her knees to seek

executive clemency from the Spanish Governor General Polavieja, that

would save her son’s life. This story had something to do with my

reluctance to believe that capital punishment should ever be carried

out. As a matter of fact, during my presidency, no man ever went to

the electric chair. At the last moment I always stayed the hand of

the executioner.”

Quezon’s opposition to the death penalty was known even before he became

president. Vicente Y. Sotto (great uncle of the current Senate

president; a journalist, lawyer, and senator from 1946 to 1950), in a

June 9, 1936, open letter in the Tribune, quoted Quezon’s prior

pronouncement on the death penalty to urge him not to waver in his

stance even as he was already president. Sotto quoted Quezon as

saying:

“Killing a man for the mere pleasure of seeing him suffer, just because he has

committed a crime, is barbarous and should not be tolerated by

progressive governments. Only those possessed of reactionary minds

can find any justification in the old Talon law … Society punishes

a criminal not because it delights in the suffering of a man, but

because it wants to be protected against violations of the law. To

kill a man is to eliminate him entirely. It does not reform him, nor

does it serve as a deterrent, since capital punishment has existed

from time immemorial and yet crimes are still being committed.”

Quezon, though, did not campaign for an end to capital punishment. In the

1934 Constitutional Convention, delegate Juan Ortega of Rizal pushed

for the abolition of the death penalty. His co-advocate delegate

Manuel Lim of Manila managed to bring it to the floor of the

convention as part of an amendment to the Bill of Rights. After a

spirited debate, voting viva voce, the convention turned down the Lim

amendment.

Quezon was going against the sentiment of political leaders. Still, this he

said during the 1935 presidential campaign (again, from the Sotto

letter):

“I expect that, should I be elected, I would not find myself in a

situation to sign a death sentence because I believe in life, I

myself enjoy life and love humanity. What the government could do is

to see to it that the people are contented and satisfied to prevent

anybody from thinking of stealing or killing.

Not a single execution happened during Quezon’s presidency, which ended

with his passing on August 1, 1944. (To be continued)

(Joel F. Ariate Jr. is a university researcher at the Third World

Studies Center, College of Social Sciences and Philosophy, University

of the Philippines Diliman.)