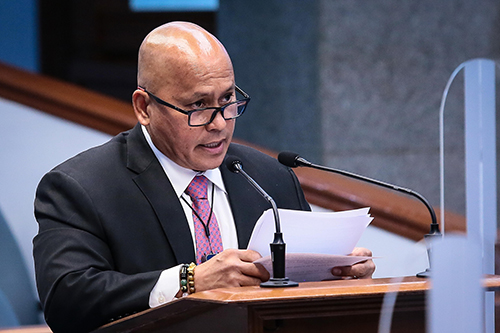

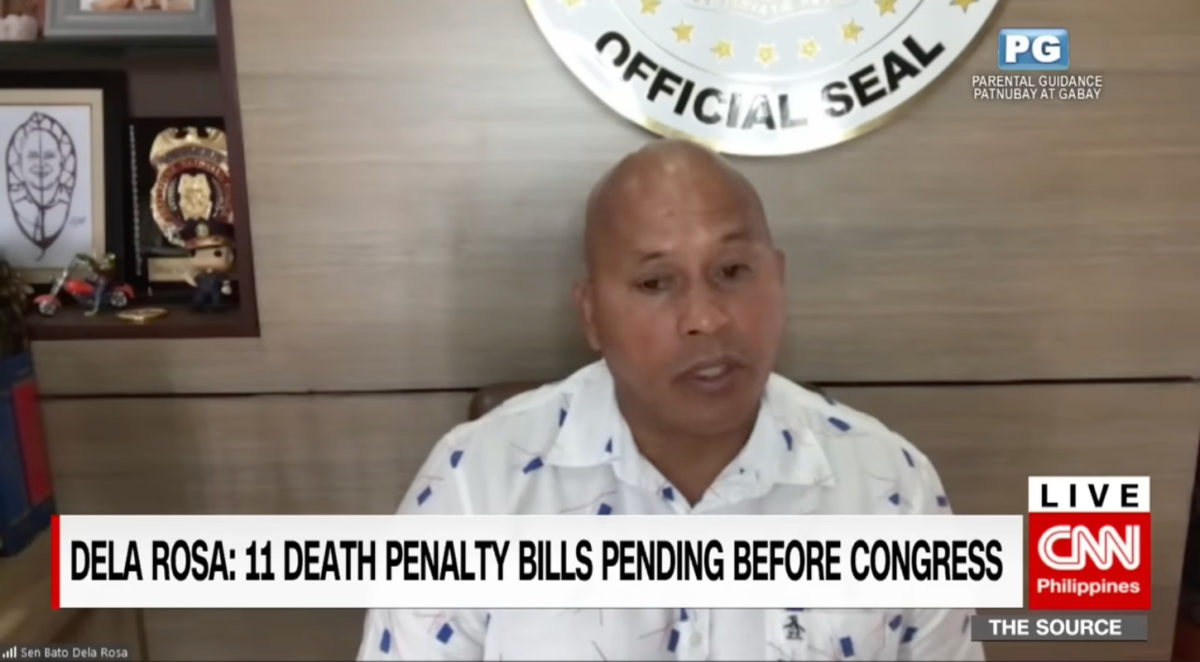

Sen. Ronald “Bato” Dela Rosa misled fellow lawmakers and the public when he cherrypicked the findings of a 2017 Inquirer report to bolster his stance for the revival of capital punishment in the country.

STATEMENT

During the Senate plenary session on July 29, Dela Rosa, former police and corrections chief, claimed that since Republic Act 7659, which restored the death penalty, was repealed in 2006, the country:

“…witnessed the horrors of [the] increasing trend of crime rate, particularly those that involved drug trafficking.”

He then said:

“According to a news article published (on) January 29, 2017, the Philippines saw a decrease in crime rate when the death penalty was imposed for heinous crimes in 1993. Crime rate decreased from 145.7 in 1993 to 98 in 1998.”

Source: Senate of the Philippines, Senate Session No. 2 (July 29, 2020), July 29, 2020, watch from 55:10 to 55:17 and from 55:19 to 55:41

FACT

While Dela Rosa did not specify the “news article” to which he was referring, a Google Advanced Search using the keywords “crime rate,” “death penalty,” “decrease,” and the time period he mentioned led to an Inquirer.net report published on Jan. 29, 2017 titled “Looking at the numbers behind death penalty.”

The report, indeed, said the country’s crime rate decreased by almost 50 percentage points, from 145.7 percent in 1993 to 98 percent in 1998. However, Dela Rosa conveniently left out other important findings in the story.

Immediately after mentioning the crime rate decrease from 1993 to 1998, the Inquirer report said:

“In 1999, however, when six of the seven executions under the Estrada administration happened, the crime rate rose to 111 [percent].”

Source: Inquirer.net, Looking at the numbers behind death penalty, Jan. 29, 2017

This is consistent with the crime data published by the Philippine Statistics Authority (PSA), based on official police records, which show that the crime rate in the country fluctuated from 1993 to 2006.

The statistical yearbooks published by the agency across this period contained minor inconsistencies. Thusly, VERA Files accessed the latest available figures for each year.

Based on PSA’s 2005 statistical yearbook, the crime rate of 145.7 per 100,000 population in 1993 gradually sunk to 97.8 percent in 1998, but again increased to 110.5 percent the following year.

The figures continued to see-saw up to 2006, based on data from PSA’s 2008 (from 2000 to 2004) and 2014 (from 2005 to 2006) statistical yearbooks.

Dela Rosa’s claim that the country “witnessed the horrors of [the] increasing trend of crime rate” after 2006 was also misleading.

Crime rate went down by around 14.02 percentage points the year after the death penalty was repealed, from 82.57 percent in 2006 to 68.55 percent in 2007, then slightly up again at 74.75 percent in 2008.

It ballooned to over 550 percent the following year. However, PSA yearbooks starting 2010 note that crime data from 2009 onward “cannot be compared to data from previous years” due to a new method of crime reporting that altered data parameters.

In 2009, the Philippine National Police (PNP) adopted the National Crime Reporting System (NCRS), which requires all PNP units to report crime incidents to the national headquarters for “centralized recording,” according to PSA.

Since then, PNP has depended on the Unit Crime Periodic Report, a blotter-based system of reporting, as its basis for recording crime data to “promote consistency in recording crime incidence.”

In a 2012 news report, then PNP deputy director general Alan Purisima told The Philippine Daily Inquirer that:

“Before [2009], the crime volume in the country was probably one of the lowest (in the world) because we were not reporting the crimes correctly as they happened.”

These findings were also mentioned in the 2017 news report Dela Rosa cited in his speech.

VERA Files has requested for updated crime data from PNP, but has yet to receive a response.

BACKSTORY

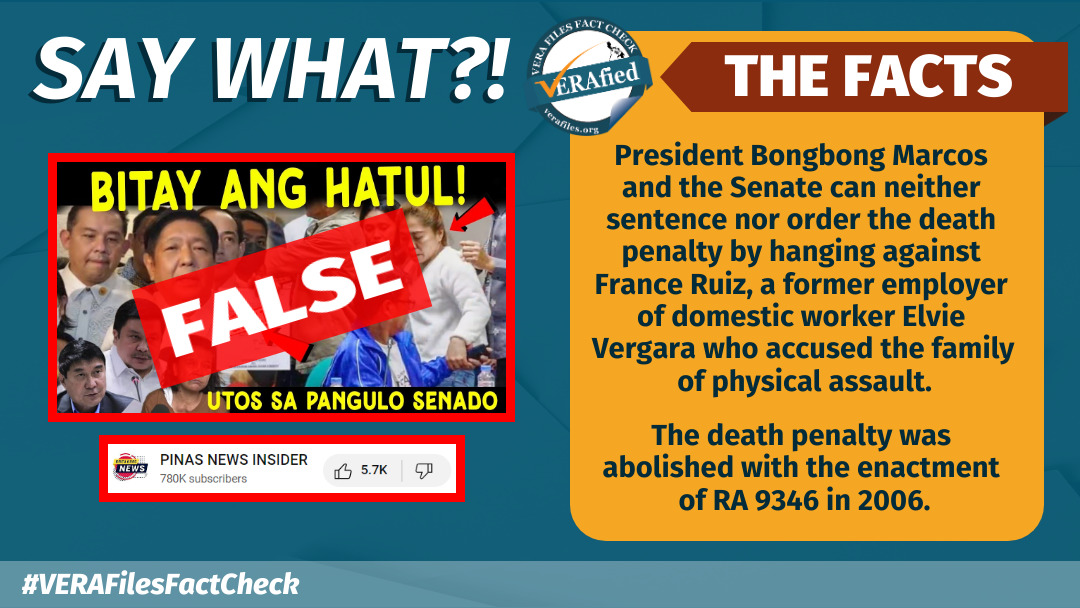

Enacted in 1993, the death penalty was abolished over a decade later in 2006 through RA 9346, signed by then president Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo.

Following the repeal, the Philippines became a party to the Second Optional Protocol, a side agreement to the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), which was signed and ratified on Dec. 19, 1966, and Oct. 23, 1986, respectively. The Second Optional Protocol explicitly forbids signatory states from conducting executions within their respective jurisdictions.

Article 6 of the ICCPR also specifies that the “sentence of death may be imposed only for the most serious crimes” in countries which have not abolished the death penalty.

The 2007 report of the UN Special Rapporteur on extrajudicial, summary, or arbitrary executions Philip Alston stated that the UN Commission on Human Rights and UN Human Rights Committee determined “drug trafficking” and “corruption,” among other offenses, as falling outside the scope of the “most serious crimes” for which the death penalty may be imposed.

In his fifth State of the Nation Address on July 27, President Rodrigo Duterte repeated his call for the “swift passage of a law reviving the death penalty by lethal injection,” specifically on crimes under the Comprehensive Dangerous Drugs Act, claiming it will not only help “deter criminality” but also “save our children” from illegal drugs.

At least 11 bills are pending in the Senate, including Senate Bill 226 authored by Dela Rosa, and 13 in the House of Representatives seeking to revive the death penalty.

Sources

Senate of the Philippines, Senate Session No. 2 (July 29, 2020), July 29, 2020

INQUIRER.net, Looking at the numbers behind death penalty, Jan. 29, 2017

Crime statistics

- Philippine Statistics Authority, 2005 Philippine Statistical Yearbook, Select Table 17.3 under “Chapter 17: PUBLIC ORDER, SAFETY, and JUSTICE”, Accessed July 31, 2020

- Philippine Statistics Authority, 2008 Philippine Statistical Yearbook, Select Table 17.3 under “Chapter 17: PUBLIC ORDER, SAFETY, and JUSTICE”, Accessed July 31, 2020

- Philippine Statistics Authority, 2014 Philippine Statistical Yearbook, Select Table 17.3 under “Chapter 17: PUBLIC ORDER, SAFETY, and JUSTICE”, Accessed July 31, 2020

- Philippine Statistics Authority, 2018 Philippine Statistical Yearbook, Select Table 17.3 under “Chapter 17: PUBLIC ORDER, SAFETY, and JUSTICE”, Accessed July 31, 2020

- Philippine Statistics Authority, 2010 Philippine Statistical Yearbook p. 576, Accessed July 31, 2020

Philippine National Police, UNIT CRIME PERIODIC REPORT, April 22, 2009

Philippine Daily Inquirer, PNP: Rise in crime due to reporting system, not failure of cops, Nov. 12, 2012

Official Gazette, Republic Act No. 9346, June 24, 2006

Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, Second Optional Protocol to the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, aiming at the abolition of the death penalty, Dec. 15, 1989

United Nations Treaty Collection, International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, Dec. 16, 1966

United Nations Office of the High Commissioner on Human Rights, International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, Dec. 16, 1966

United Nations Office of the High Commissioner on Human Rights, Report of the Special Rapporteur on Extrajudicial, Summary or Arbitrary Executions, UN Doc. A/HRC/4/20, March 2007

RTVMalacanang, President Rodrigo Duterte’s 5th State of the Nation Address (SONA) 7/27/2020, July 27, 2020

Senate of the Philippines, Senate Bill 226

(Guided by the code of principles of the International Fact-Checking Network at Poynter, VERA Files tracks the false claims, flip-flops, misleading statements of public officials and figures, and debunks them with factual evidence. Find out more about this initiative and our methodology.)