(This article was first published on July 15, 2019. We are reposting this as the public weighs in on the bills filed restoring death penalty.)

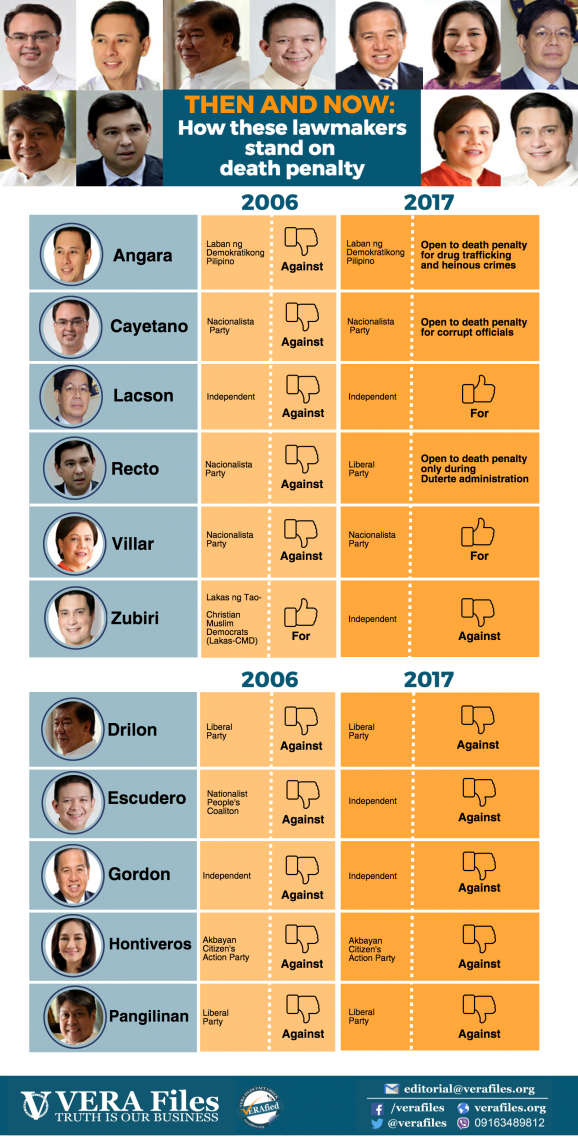

A week after assuming office, neophyte senators Christopher “Bong” Go and Ronald “Bato” dela Rosa proposed the reinstatement of the death penalty through Senate Bills (SB) 207 and 226, respectively. Two incumbent senators refiled what they had proposed before: Ping Lacson sent in SB 27, Manny Pacquiao SB 189.

Before filing SB226, Dela Rosa verbally expressed his desire to have criminals guilty of drug trafficking executed in public by firing squad with live media coverage. He assumed that it will be a deterrent:

”Yung gawing public na maging katakot-takot sa mga tao na gumawa, para hindi pamarisan.

(To make it publicly gruesome to the people who committed it so others will be deterred from committing the same crime.) ”

The bill that he filed, though, specifies no measure on how convicts should be executed or whether the execution should be made public at all. He said he changed his mind on the matter after hearing out a plea from one of his daughters.

A week later, when pressed by broadcast journalist Karen Davila for proof that the death penalty deters crime, Senator dela Rosa brushed aside the issue by saying that nothing will get done if proof is always demanded. The import of his proposed legislation lies in his own personal experience as former head of the Bureau of Corrections, and not in some scientific research. He claimed a convicted Chinese drug lord advised him that the only way to stop the drug trade is to execute those who are involved in drug trafficking.

So, this is now how we conduct policy making and legislation. A situation not far removed when kings handed down laws and executions were, by design, a carnival of horror— half a millennium ago. If the history of capital punishment in the Philippines is any indication, its imposition has always proven to be a regressive step, both in dealing with criminality and in assigning value to human dignity.

The theater of the macabre

Based on the accounts of 16th- and 17th-century Spanish priest chroniclers like Francisco de Santa Ines, Juan Francisco de San Antonio, Joan de Plaçençia, and Francisco Colin, indigenous Philippine society practiced the death penalty. The condemned can be tied to a post and speared or whipped to death, hanged, or simply stabbed by the offended party as authorized by the village chief. The accounts were unclear, if not silent, if other people in the community were made witness to such executions. But distinct in imposing death as punishment in early Philippine societies was the chance given to the culprit to negotiate his or her way out of it. One can settle the penalty of death by either paying in gold or making one’s self a slave to the offended party.

Only with the founding of the Spanish colonial regime in the 16th century did executions start to approximate what Dela Rosa and fellow pro-death penalty legislators may have in mind on why and how the death penalty should be imposed.

In 1588, Estevan de Marquina, notary public of Manila, wrote in his report that Agustin de Legazpi and Martin Panga, leaders of a conspiracy of an uprising against the Spaniards, “being convicted by witnesses, were condemned to be dragged and hanged; their heads were to be cut off and exposed on the gibbet in iron cages, as an example and warning against the said crime.”

Basi Revolt painting by Esteban Villanueva, c. 1807; photograph by Lianne777 . Wikipedia

Two hundred years later, the Spanish colonial authority still relied on the theater of the macabre to stamp the power of the king on the bodies of colonial subjects. And the Filipinos seemed to keep on failing to learn the lesson of the gallows and of mutilated corpses not to revolt against Spain. In 1807, leaders of the Basi Revolt in Piddig, Ilocos Norte, were hanged; their heads were then cut off, put inside cages, and displayed in public places.

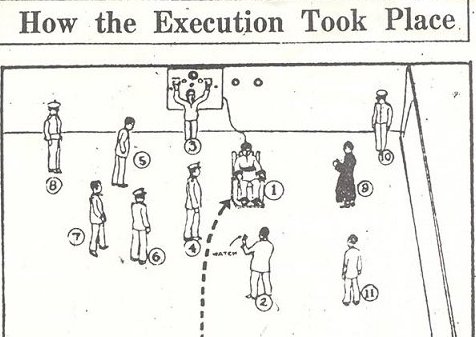

In a span of two centuries, the key changes introduced in imposing the death penalty were in the methods of execution: firing squad and garrote. Death by musketry was reserved for those tried in a military tribunal, often for treason, rebellion, and sedition–crimes against the king and the state. In 1841, for example, Apolinario de la Cruz, a leader of a revolt in Southern Luzon, was executed by a firing squad and his body was dismembered and exhibited in public.

In the 19th century, Madrid repeatedly ordered that hanging be done away with. The first order to have reached Manila came out in 1812. Instead of strict observance, however, the first half of the 19th century saw the application of all three methods of execution. Jose Montero y Vidal recorded that an April 24, 1832 decree of the King of Spain (received May 13, 1832 in Manila) ordered that hanging be abolished and replaced by the garrote. The shift in method of execution was a response to the spread of Enlightenment thought in the royal courts of Europe. Hanging and its attendant acts of mutilation were considered unspeakable acts of barbarity, which has no place in societies ever on their forward march towards civilization.

Garrote

Public garroting; top photo from Joseph Earle Stevens’ Yesterdays in the Philippines (1899), lower photo from History and Description of the Picturesque Philippines by Adjutant Ebenezer Hannaford (1900)

Orders from Madrid notwithstanding, hanging held sway in the Philippines. The garrote had to wait its turn. What remained was the bloody spectacle of executions. In an 1819 account, John White, an English traveler in Manila, described the hanging that he witnessed as a “diabolical scene.”

“The hangman was habited in a red jacket and trowsers, with a cap of the same colour upon his head . . . I know not; but never did I see such a demoniacal vis-age as was presented by this miscreant; and when the trembling culprit was delivered over to his hand, he pounced eagerly upon his victim, while his countenance was suffused with a grim and ghastly smile, which reminded us of Dante’s devils. He immediately ascended the ladder, dragging his prey after him till they had nearly reached the top; he then placed the rope around the neck of the malefactor, with many antic gestures and grimaces, highly gratifying

and amusing to the mob. To signify to the poor fellow under his fangs that he wished to whisper to his ear, to push him off the ladder, and to hump astride his neck with his heels drumming with violence upon his stomach, was but the work of an instant. We could then perceive a rope fast to each leg of the sufferer, which was pulled with violence by people under the gallows; and an additional rope, or, to use a sea term, a preventer, was round his neck, and secured to the gallows, to act in case of accident to the one by which the body was suspended.”

Yet, instead of conveying fear to the Manileños, “it was a tragic comedy” for them. The “mass of spectators . . . view the whole scene with feeling not far remote, I fear, from that kind of satisfaction which a child feels at a raree show.”

Dismembering the bodies of convicts seemed to have stopped with the introduction of the garrote. It was only after the 1887 Spanish Penal Code took effect that the use of the garrote in executions was seriously enforced. In 1890, a royal decree reiterated that the firing squad was only for those tried under the Code of Military Justice. But all executions remained public. Article 103 of the 1887 Spanish Penal Code even specified that “the corpse of the person executed shall remain exposed in the gallows for four hours.”

The 1887 Spanish Penal Code remained in effect until 1932, when the current Revised Penal Code was introduced. What the American colonizers did upon their conquest in 1898 was introduce amendments to the 1887 Spanish Penal Code to fit the imposition of the death penalty to their own regime. On December 18, 1906, the Philippine Commission Act (PCA) 1577 ordered that all executions must be done inside the Bilibid Prison in Manila. This step forward was coupled with a regressive step. Enacted on September 2, 1902, PCA 451 brought back hanging as a mode of execution. PCA 1577 was also not applicable in Muslim Mindanao.

Execution of insurgents. Photo from Major G. J. Younghusband’s The Philippines and Round About (1900)

Hanging, the use of firing squad, and public execution—brutal remnants of monarchic and imperial penal regimes—will be revisited and reapplied in the 20th century by regimes seeking vengeance and ever conscious of appearing tough on crime. Right after the end of World War II, 17 Japanese soldiers were hanged in the New Bilibid Prison in Muntinlupa. Generals Tomoyuki Yamashita and Masaharu Homma, erstwhile leaders of the Japanese forces in the Philippines sentenced to death by American military tribunals for their supposed war crimes, met their fates differently inside a prison camp in Los Baños, Laguna. Yamashita was hanged; Homma was executed by a firing squad. In possible consideration of Homma’s tenuous involvement in the crimes with which he was charged, the military tribunal was said to have afforded him the honor of a soldier’s death.

Lim Seng

The execution by firing squad of convicted drug Lim Seng . Screengrab from the documentary Batas Militar.

Twenty-seven years after Homma’s death by musketry, another death squad was formed and ordered by a military tribunal to carry out an execution. But this time, it was not a matter of honor. The January 15, 1973, execution of Lim Seng for drug charges was a high point in propaganda for Ferdinand Marcos’ dictatorial regime. It was meant to put an end to the illegal drugs trade during that era. Though Lim was originally tried and sentenced to life imprisonment in a civilian court, Marcos decreed that his case be tried in a military tribunal. His execution was witnessed by thousands in the early morning hours in Fort Bonifacio. It was also an on-camera execution, making possible its broadcast in television and repeated showing in cinemas.

And nearly 45 years later, the recording of said execution finally made its way into social media, again for everyone to see.

Marcos propagandists take pride that under his martial law regime, “He did not implement a Death Penalty to a Filipino during and after Martial Law.” One can read that in a huge poster in Marcos’s World Peace Center in Batac. Lim was Chinese after all. But what of Epifanio Pujinio, Salvador Egang, Gaudencio Mongado, Belesande Salar, Jilly Segador, Causiano Enot, Nicolas Layson, Cesar Ragub, Cesar Fuguso, Leonardo Dosal, Juan Galicia, and Marcelo San Jose? Their pictures hang in the New Bilibid Prison in Muntinlupa, in the gallery of convicts executed by electric chair from July 31, 1973 until October 21, 1974.

Even historian Alfred McCoy bought the Marcos lie before offering this critique:

“Lim Seng would become the only criminal legally executed in the 14 years of martial law. But there would be thousands of extrajudicial killings of labor leaders, student activists, and ordinary citizens, their bodies mangled by torture and dumped for display to induce terror.”

Isn’t this where we are again today? (To be continued)

(Joel F. Ariate Jr. is a university researcher at the Third World Studies Center, College of Social Sciences and Philosophy, University of the Philippines Diliman.)