FULL text of the House prosecutors’ reply to Chief Justice Renato Corona’s answer to the impeachment complaint transmitted by the House of Representatives to the Senate.

Republic of the Philippines

Congress of the Philippines

Senate

SITTING AS THE IMPEACHMENT COURT

IN THE MATTER OF THE IMPEACHMENT OF RENATO C. CORONA AS CHIEF JUSTICE OF THE SUPREME COURT OF THE PHILIPPINES.

Case No. 002-2011

REPRESENTATIVES NIEL C. TUPAS, JR., Et. Al., (other complainants comprising at least one third (1/3) of the total Members of the House or Representatives as are indicated below.)

x——————————————————-x

ANSWER

[TO VERIFIED COMPLAINT FOR IMPEACHMENT, 12 DECEMBER 2011]

Chief Justice Renato C. Corona, through his undersigned counsel, most respectfully states:

PREFATORY STATEMENT

The sin of Pontius Pilate is not that he exercised his powers, but that he abandoned his judgment, washed his hands and let the angry mob have its way.

1. Impeachment, for Chief Justice Renato C. Corona (“CJ Corona”), came like a thief in the night. Even as he stands before this Tribunal to defend himself, his greatest fear is the danger that lady justice herself must face.

2. In blitzkrieg fashion, 188 Members of the House of Representatives signed the Articles of Impeachment, causing the immediate transmission of the complaint to the Senate. Almost instantly, some Members the of House resigned from the majority coalition, amidst complaints of undue haste in the filing of the Articles of Impeachment. It appears that Members were expected to sign on being offered tangible rewards, even if denied the opportunity to read the Articles of Impeachment and examine the evidence against CJ Corona.

3. The nation remains in a state of bewilderment, stunned to see that the members of the House of Representatives were able to come together on such short notice, to decisively act on a matter that they had no knowledge of the week before! To this day, the public’s proverbial mind is muddled with questions about the fate of the so-called priority bills long covered with mildew and buried in cobwebs. While the swift impeachment action of the House of Representative is nothing short of miraculous, it also has the distinction of being the single most destructive legislative act heretofore seen.

4. A fair assessment of the prevailing political climate will support the contention that the filing of the Articles of Impeachment was the handiwork of the Liberal Party alone. Surely, one cannot ignore the inexplicable readiness of the Members of the House to instantly agree to sign the Articles of Impeachment. Without much effort, one reaches the inevitable conclusion that President Benigno C. Aquino III as, the head of the Liberal Party, must have been “in” on the plan from inception. In contrast, it is unlikely that President Aquino knew nothing of the plans to impeach the Chief Justice.

5. There is little doubt about the desirability of having a friendly, even compliant, Supreme Court as an ally. Any president, Mr. Aquino included, hopes for a Supreme Court that consistently rules in his favor. Ensuring political advantage would amply justify the allegation that President Aquino seeks to subjugate the Supreme Court. More importantly, however, many circumstances and events dating back to the election of President Aquino support the conclusion that it was he who desired to appoint the Chief Justice and who instigated and ordered the filing of impeachment charges to remove Chief Justice Corona.

6. Even before assuming office, President Aquino was predisposed to rejecting the appointment of CJ Corona, viz.:

* * Aquino had said he does not want to take his oath of office before Corona.

At the very least I think his appointment will be questioned at some future time. Those who chose to side with the opinion that the president cannot appoint also excused themselves from nomination. At the end of the day I do not want to start out with any questions upon assumption of office, Aquino said. [1]

7. Indeed, when the time came for President-elect Aquino to take his oath, he opted to do so before Justice Conchita Carpio-Morales. And, though Chief Justice Corona was among the guests at his inauguration, as dictated by protocol, the President snubbed him.

8. On 1 December 2011, at an address before foreign investors, President Aquino – in reference to Dinagat Island Cases and the issuance of a Temporary Restraining Order allowing GMA to exercise her right to travel abroad – called the Supreme Court and its Members “confused” for derailing his administration’s mandate. The most virulent attack from the President came on 5 December 2011, when President Aquino openly attacked CJ Corona at his infamous address during the National Criminal Justice Summit, deriding the appointment of the Chief Justice and calling it a violation of the Constitution. [2] These speeches followed on the heels of the promulgation of the decision in Hacienda Luisita, Incorporated v. Presidential Agrarian Reform Council, et al. ,[3] where the Supreme Court ordered the distribution of the lands of the Hacienda owned by President Aquino’s family, to the farmer beneficiaries. As if on cue, after the President’s speeches, that members of the House of Representatives adopted signed the Articles of Impeachment against CJ Corona.

9. What we have before us, then, is a Complaint born out of the bias against CJ Corona and the predisposition to destroy him by associating him with the unpopular former President Gloria Macapagal Arroyo and by misinterpreting his concurrence to certain Supreme Court decisions as protecting former President Arroyo. What we also have are hidden forces who will be benefited by CJ Corona’s ouster and who are conspiring and causing intrigue behind the scene to ensure his removal and their re-emergence into power to the detriment of the Bench, Bar and the populace. Certainly, such cannot be the backdrop, purpose and consequence of impeachment.

10. The impeachment process – while admittedly political in character – has therefore become a partisan orgy, devoid of any mature deliberation and of lawful purpose whatsoever, especially in a precedent-setting and historic event involving no less than the impeachment of the Chief Justice of the Philippines. When impeachment results from a rushed, partisan and insidious attempt to unseat a sitting Chief Justice, instead of a rational and careful debate on the merits of the Articles of Impeachment, the arbitrariness of such an act comes to the fore, taints the process and amounts to an unveiled threat against the other justices of the Supreme Court.

11. The past events depict an Executive Branch that is unwilling to brook any opposition to its power, particularly in prosecuting high officials of the former Administration. When the Chief Justice took his solemn oath to uphold the law and dispense justice without fear or favor, that oath did not carve an exception with respect to actions of the President of the Philippines. After all, the Rule of Law is not the rule of the President. As landmark jurisprudence puts it, it is the province of the Supreme Court to say that what the law is. When the Supreme Court decides a case, it is a collective decision of the Court. It is not a decision of the Chief Justice alone.

12. The noble purpose of impeachment is to spare the nation from the scourge of an undesirable public official who wields power in disregard of the constitutional order. It is a drastic appeal to restore respect for the sovereignty of the people. Tragically, the Verified Impeachment Complaint is not such a noble impeachment of Chief Justice Corona; facially, it is a challenge to certain orders and decisions of the Supreme Court, misperceived as an effrontery to Executive and Legislative privileges. In reality, however, this impeachment seeks mainly to oust CJ Corona and such number of justices that will not bend to the powerful and popular chief executive.

13. This intemperate demonstration of political might is a fatal assault on the independent exercise of judicial power. Falsely branded as an attempt at checks and balances – and even accountability – we are witnessing a callous corruption of our democracy in this staged impeachment. Never in the history of this nation has the Republican system of Government under the Constitution been threatened in such cavalier fashion. Chief Justice Corona bears the happenstance of leading the Supreme Court in the face of a political crusade that readily sacrifices the Rule of Law to its thirst for popularity.

14. The impeachment of CJ Corona is thus a bold, albeit ill-advised attempt by the Executive Branch (with the help of allies in the House of Representatives) to mold an obedient Supreme Court. The fundamental issue before this hallowed body transcends the person of the Chief Justice. What is at stake then is the independence of the Supreme Court and the Judiciary as a whole. Because the impeachment of Chief Justice Corona is an assault on the independence of the Judiciary, it is nothing less than an attack on the Constitution itself.

15. Our constitutional system – with its bedrock principles of Separation of Powers and Checks and Balances – simply cannot survive without a robust and independent Judiciary. An independent Supreme Court and Judiciary, which is an essential foundation of our democratic system of government, cannot be allowed to dissolve into hollow words from its fragile living reality.

16. The Senate of the Philippines – whose own history of independence has kept the Nation in good stead – is now called upon to protect the Judiciary’s independence under the Constitution and save the Nation from the abyss of unchecked Executive power. In these proceedings, the responsibility of protecting the Judiciary belongs to the Senate. Only through a fair and judicious exercise of its judgment can the Senate restore productive co-existence within the trinity of the Republic’s 3 great branches.

17. Fortunately, the experience of challenges to judicial independence of other democracies may prove enlightening:

No matter how angry and frustrated either of the other branches may be by the action of the Supreme Court, removal of individual members of the Court because of their judicial philosophy is not permissible. The other branches must make use of other powers granted them by the Constitution in their effort to bring the Court to book. [4]

18. In these proceedings, attention will therefore be repeatedly drawn to certain general principles central to a correct resolution of the issues. The most fundamental of these principles is the rule that a man is responsible only for the natural, logical consequences of his acts. Conversely, a man cannot be held responsible for that which is not his doing. The related rule of parity provides that there must be identical consequences for identical acts, and to punish one for his acts, but not another, is to have no law at all.

19. It bears stressing that these general principles are not technical rules of law, but are rules drawn honored by the long experience of usage in civilized society; honored not by force of law, but because of their inherent logic and unquestionable fairness, proving themselves able to render satisfactory resolution in countless situations, again and again. These rules emanate not so much from the exercise of legislative power, but from an inherent sense of justice that each individual understands.

20. These are the principles and rules that favor the case of Chief Justice Corona. Be that as it may, unless this august Senate heeds his pleas for justice and reason and lends its protective intercession against a determined executive, Chief Justice Corona could well be the last defender of judicial independence. After him, there may be nothing left to protect.

21. In this battle for the preservation of our democracy, CJ Corona draws courage and impetus from the words of the eminent constitutionalist, Joaquin G. Bernas, S.J. –

In this critical moment of our constitutional history, my hope is that the justices of the Supreme Court, imperfect though they may be, will not capitulate and that others in the judiciary will not tremble in their boots and yield what is constitutionally theirs to the President. If they do, it would be tragic for our nation. [5]

ADMISSIONS

1. CJ Corona, only insofar as the same are consistent with this Answer, admits the allegations in the Verified Complaint for Impeachment dated 12 December 2011 (“the Complaint”) regarding the identities and circumstances of “The Parties,” his appointment as stated in paragraph 3.1 and qualifies the admission by declaring that he rendered service as an officer of the Offices of the Vice President and President, and not of Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo (GMA).

2. CJ Corona further admits par. 3.5.3 of the Complaint with the qualification that he granted the request for a courtesy call only to Mr. Dante Jimenez of the Volunteers Against Crime and Corruption (VACC). However, Lauro Vizconde appeared with Mr. Jimenez at the appointed time, without prior permission or invitation.

3. With respect to par. 7.6, CJ Corona admits the same but takes exception to the allegation that there is a pre-condition to the temporary restraining order referred to therein.

4. Furthermore, CJ Corona admits paragraphs 1.1, 2.1, 3.2, 3.3.5, 3.3.6, 3.4.6, 3.5.1, 3.5.7, 4.1, 5.1, 5.2, 6.1, and 6.2, only as to the existence of the constitutional provisions, decisions, resolutions, orders and proceedings of the Supreme Court of the Philippines cited in these paragraphs.

DENIALS

1. CJ Corona denies the following:

2. All the paragraphs under “Prefatory Statement,” for being mere conclusions, conjecture or opinions, without basis in fact and law.

3. Certain paragraphs under “General Allegations” —

4. The first and second paragraphs,[6] the truth being that the legality of the appointment of CJ Corona was passed upon and decided by the Supreme Court En Banc in De Castro v. Judicial and Bar Council, et al. and consolidated petitions,[7] the merits of which are not the subject of a review before this Impeachment Court.

5. The third, fourth, fifth, seventh and eighth paragraphs,[8] for being mere opinions or conjectures, without basis in fact and in law.

6. The sixth paragraph,[9] for lack of knowledge and information sufficient to form a belief over the alleged matters, irrelevant to these proceedings.

7. All of the “Grounds for Impeachment,” the “Discussion of the Grounds for Impeachment,” specifically paragraphs 1.2, 1.3, 1.4, 1.5, 1.6, 1.7, 1.8, 1.9, 1.10, 1.11, 1.12, 1.13, 1.14, 1.15, 2.2, 2.3, 2.4, 3.3, 3.3.1, 3.3.2, 3.3.3, 3.3.4, 3.4, 3.4.1, 3.4.2, 3.4.3, 3.4.4, 3.4.5, 3.4.7, 3.4.8, 3.4.9, 3.4.10, 3.5, 3.5.2, 3.5.4, 3.5.5, 3.5.6, 3.5.8, 3.5.9, 3.5.10, 3.5.11, 3.6, 3.6.1, 3.6.2, 3.6.3, 3.6.4, 3.6.5, 4.2, 4.3, 4.4, 5.3, 5.4, 5.5, 5.6, 5.7, 5.8, 5.9, 5.10, 5.11, 5.12, 5.13, 5.14, 5.15, 5.16, 6.3, 6.4, 6.5, 7.1, 7.2, 7.3, 7.4, 7.5, 7.7, 7.8, 7.9, 7.10, 7.11, 8.2, 8.3, and 8.4, the truth being as discussed hereunder.

DISCUSSION OF SPECIFIC DENIALS

AND AFFIRMATIVE DEFENSES

PRELIMINARY OBJECTIONS

1. The Complaint is insufficient in substance and form.

2. The Constitution requires that the House of Representatives shall have the exclusive power to initiate all cases of impeachment. [10] This Complaint was filed pursuant to Section 3(4) of Article XI, which provides:

Sec. 3(4) In case the verified complaint or resolution of impeachment is filed by at least one-third of all the members of the House, the same shall constitute the Articles of Impeachment, and trial by the Senate shall forthwith proceed.

3. The Impeachment Court may not proceed to trial on the basis of this Complaint because it is constitutionally infirm and defective, for failure to comply with the requirement of verification. Attention is called to the Verification of the Complaint which states that each of the signatories “read the contents thereof. ”

4. Undoubtedly, public admissions by members of the House of Representatives declared that there was no opportunity to read the Complaint. They also declared that the majority of signatories signed without reading the Complaint, but reputably in exchange for material considerations.[11] It stands to reason that the House of Representatives had no authority under the Constitution to transmit the Articles of Impeachment for trial before the Senate.

5. Under Section 4, Rule 7 of the Rules of Court, a pleading is verified by an affidavit that the affiant has read the pleading and that the allegations therein are true and correct of his personal knowledge and based on authentic records. In this case, however, the requirement of verification is not a mere procedural rule but a constitutional requirement. In other words, failure to meet the requirement renders the impeachment of CJ Corona unconstitutional.

6. Section 3(4) of Article XI of the Constitution further requires that the verified Complaint is filed by at least one-third of all members of the House. In direct violation of this provision, the Complaint was initiated by President Aquino, and filed by his sub-alterns. Accordingly, the complaint could not be directly transmitted to the Senate.

7. CJ Corona adopts and repleads the Prefatory Statement.

8. It is an extremely rare event when the present House of Representatives instantly musters 188 votes for any matter pending before it, including those described as urgent legislation. [12] Surely, the blitzkrieg adoption of the Complaint was only possible by the indispensable concerted action of the majority coalition, dominated by the Liberal Party[13] headed by President Aquino.

9. In consideration of the available evidence, CJ Corona reserves his right to request for compulsory processes to elicit and adduce evidence on his behalf regarding matters indispensable for the resolution of this case. [14]

ARTICLE I

Alleged Partiality to the GMA Administration

1. CJ Corona denies Article I.

2. CJ Corona specifically denies pars.1.2, 1.3, 1.4, 1.5, 1.6, 1.7, 1.9, 1.10, 1.11, 1.13, 1.14, 1.15, in so far as these allege and insinuate that CJ Corona betrayed public trust when he supposedly showed partiality and subservience to protect or favor his alleged benefactor or patroness, GMA and her family, by shamelessly accepting his midnight appointment as Chief Justice.

3. To begin with, Complainants do not define “betrayal of public trust” as a ground for impeachment. Betrayal of public trust in the impeachment of a responsible constitutional officer is not a catch-all phrase to cover every misdeed committed. As a ground for impeachment, betrayal of public trust must be at the same level of committing treason and bribery or offenses that strike at the very heart of the life of the nation. [15] Betrayal of public trust should be limited to grave violations of the most serious nature, lest impeachable officers fall prey to all sorts of frivolous charges.

4. Further, the nature of the office of constitutionally-tenured government officials, like the Chief Justice, requires that they remain independent and insulated from political pressures. The right to be removed only by impeachment is the Constitution’s strongest guarantee of security of tenure[16] and independence. Otherwise, impeachable officers will be vulnerable to scheming individuals concocting sham impeachment charges to accomplish their selfish agendas.

5. By mentioning the decisions and actions of the Supreme Court in paragraphs 1.2, 1.6, 1,7, 1.11, 1.14, and 1.15, Complainants demonstrate their lack of understanding of the concept of a collegial body like the Supreme Court, where each member has a single vote. Whether he be the Chief Justice or the most junior associate, his vote is of equal weight with that of the others.

6. Unlike the Chief Justice, the President of the Philippines has control “of all the executive departments, bureaus, and offices. ” This means that he has the power to reverse, or “alter or modify or nullify or set aside what a subordinate officer had done in the performance of his duties and to substitute the judgment of the former for that of the latter. ”[17]

7. The authority of the Chief Justice is like that of the Senate President with respect to laws voted for approval. They both cast just one vote, equal to the vote of every member of the body. The Chief Justice has no control over any Justice of the Supreme Court. The decision of the Supreme Court, either by division or en banc, is a result of the deliberative process and voting among the Justices. Each Justice has the prerogative to write and voice his separate or dissenting opinion. A concurrence of the majority, however, is needed to decide any case.

8. It must be emphasized that CJ Corona cannot be held accountable for the outcome of cases before the Supreme Court which acts as a collegial tribunal. This is the essence of the system of justice before the Supreme Court, as mandated by the Constitution. In In Re: Almacen,[18] the Court through Chief Justice Fred Ruiz Castro elucidated on the nature of a collegial court:

Undeniably, the members of the Court are, to a certain degree, aggrieved parties. Any tirade against the Court as a body is necessarily and inextricably as much so against the individual members thereof. But in the exercise of its disciplinary powers, the Court acts as an entity separate and distinct from the individual personalities of its members. Consistently with the intrinsic nature of a collegiate court, the individual members act not as such individuals but only as a duly constituted court. Their distinct individualities are lost in the majesty of their office. So that, in a very real sense, if there be any complainant in the case at bar, it can only be the Court itself, not the individual members thereof—as well as the people themselves whose rights, fortunes and properties, nay, even lives, would be placed at grave hazard should the administration of justice be threatened by the retention in the Bar of men unfit to discharge the solemn responsibilities of membership in the legal fraternity. ” (Emphasis supplied) [See also Bautista vs. Abdulwahid[19] and Santiago vs. Enriquez. [20]]

9. In effect, the Complaint calls upon the Impeachment Court to review certain decisions of the Supreme Court. This cannot be done; it is beyond any reasonable debate. It is an essential feature of the checks and balances in a republican form of government that no other department may pass upon judgments of the Supreme Court. This is the principle of separation of powers. According to Maglasang v. People:[21]

We further note that in filing the “complaint” against the justices of the Court’s Second Division, even the most basic tenet of our government system — the separation of powers between the judiciary, the executive, and the legislative branches has — been lost on Atty. Castellano. We therefore take this occasion to once again remind all and sundry that “the Supreme Court is supreme — the third great department of government entrusted exclusively with the judicial power to adjudicate with finality all justiciable disputes, public and private. No other department or agency may pass upon its judgments or declare them ‘unjust. ‘” Consequently, and owing to the foregoing, not even the President of the Philippines as Chief Executive may pass judgment on any of the Court’s acts. “ (Emphasis and underscoring supplied) [See also In Re: Laureta[22] and In Re: Joaquin T. Borromeo. Ex Rel. Cebu City Chapter of the Integrated Bar of the Philippines]. [23]

10. Complainants allege in par. 1.2 that CJ Corona betrayed public trust when he shamelessly accepted his “midnight appointment” as Chief Justice. As already stated, his was not a midnight appointment prohibited by the Constitution. To repeat, this issue was settled by the Supreme Court in De Castro v. Judicial and Bar Council, et al. :[24]

As can be seen, Article VII is devoted to the Executive Department, and, among others, it lists the powers vested by the Constitution in the President. The presidential power of appointment is dealt with in Sections 14, 15 and 16 of the Article.

Article VIII is dedicated to the Judicial Department and defines the duties and qualifications of Members of the Supreme Court, among others. Section 4(1) and Section 9 of this Article are the provisions specifically providing for the appointment of Supreme Court Justices. In particular, Section 9 states that the appointment of Supreme Court Justices can only be made by the President upon the submission of a list of at least three nominees by the JBC; Section 4(1) of the Article mandates the President to fill the vacancywithin 90 days from the occurrence of the vacancy.

Had the framers intended to extend the prohibition contained in Section 15, Article VII to the appointment of Members of the Supreme Court, they could have explicitly done so. They could not have ignored the meticulous ordering of the provisions. They would have easily and surelywritten the prohibition made explicit in Section 15, Article VII as being equally applicable to the appointment of Members of the Supreme Court in Article VIII itself, most likely in Section 4 (1), Article VIII. That such specification was not done only reveals that the prohibition against the President or Acting President making appointments within two months before the next presidential elections and up to the end of the President’s or Acting President’s term does not refer to the Members of the Supreme Court. (Emphasis supplied)

11. Section 15, Article VII does not apply as well to all other appointments in the Judiciary. One of the reasons underlying the adoption of Section 15 as part of Article VII was to eliminate midnight appointments by an outgoingChief Executive, as contemplated in Aytona v. Castillo. [25] In fact, in In Re: Valenzuela[26] that Complainants invoke, the Court observed that the outgoing President may make appointments to important positions even after the proclamation of the new President, if they are the result of deliberate actions and careful considerations:

As indicated, the Court recognized that there may well be appointments to important positions which have to be made even after the proclamation of the new President. Such appointments, so long as they are “few and so spaced as to afford some assurance of deliberate action and careful consideration of the need for the appointment and the appointee’s qualifications,” can be made by the outgoing President. Accordingly, several appointments made by President Garcia, which were shown to have been well considered, were upheld. [27](Emphasis supplied)

12. Concretely, Complainants ignored the most crucial ruling in In re: Valenzuela, where the Supreme Court – as early as 1998 – already contemplated a situation similar to that of CJ Corona, viz:

To be sure, instances may be conceived of the imperative need for an appointment, during the period of the ban, not only in the executive but also in the Supreme Court. This may be the case should the membership of the Court be so reduced that it will have no quorum or should the voting on a particular important questions requiring expeditious resolution be evenly divided. Such a case, however, is covered by neither Section 15 of Article VII nor Section 4(1) and 9 of Article VIII. (Emphasis supplied)

13. Complainants allege in pars. 1.4, 1.5, 1.6, 1.7, 1.9, 1.10, 1.11, 1.12, 1.13, 1.14 and 1.15 that CJ Corona’s vote in decisions affecting GMA constitute betrayal of public trust. Notably, CJ Corona did not pen those decisions. He only either concurred or dissented in them. Actually, Complainants’ own table[28] shows this. He never flip-flopped or changed his vote in any of the cases mentioned.

14. Complainants cite Newsbreak’s table of Supreme Court cases[29] involving GMA’s administration, its rulings, and the CJ Corona’s votes as proof of his partiality and subservience to her. Newsbreak’s own table shows, however, that CJ Corona’s votes were not consistently pro-GMA. Although he voted for her policies in 78% of the cases, he voted against her in 22% of those cases. This negates any allegation of subservience, partiality and bias against CJ Corona.

15. In their article Judicial Politics in Unstable Democracies: The Case of the Philippine Supreme Court, an Empirical Analysis 1986- 2010, authors Laarni Escresa and Nuno Garoupa tracked 125 decisions of the Supreme Court in politically-salient cases from 1986 to 2010. The article pointed out that Justice Antonio Carpio who served as GMA’s Chief Presidential Legal Adviser cast 19 pro-administration votes as against 11 anti-administration votes or around 66% pro-GMA votes. Justice Arturo Brion, who served as GMA’s Labor Secretary cast 5 pro-administration votes against 8 anti-administration votes or around 33% pro-GMA votes. Actually, CJ Corona in this study cast 8 pro-administration votes against 28 anti-administration votes or around only 29% pro-GMA votes.

16. Contrasted with the alleged statistics from the Newsbreak table adverted to, the data of Escresa and Garoupa reveals that no conclusive evidence exists to support the allegations of Complainants.

17. Complainants also allege in par. 1.6 that CJ Corona thwarted the creation of the Truth Commission in the Biraogo case thus shielding GMA from investigation and prosecution. To be sure, the Justices of the Court tangled with each other in a spirited debate and submitted their concurring and dissenting opinions. [30] Under the circumstances, CJ Corona could neither have directed nor influenced the votes of his colleagues. Complainants insult the intelligence and independence of the other members of the Supreme Court by their illogical claim.

18. CJ Corona denies the allegations in pars. 1.7 and 1.8, that he caused the issuance of the status quo ante order (SQAO) in Dianalan-Lucman v. Executive Secretary, involving President Aquino’s Executive Order No. 2 that placed Dianalan-Lucman in the class of GMA’s midnight appointees. Although the Supreme Court did not enjoin the removal of other appointees, it issued a SQAO in favor of Dianalan-Lucman because of her unique situation. As usual, CJ Corona cast just one vote in the Supreme Court’s unanimous action.

19. Again, CJ Corona denies the allegations in pars. 1.11, 1.12 and 1.13, that he should have recused from Aquino v. Commission on Elections. The Rules of Court specify the grounds for inhibition or recusal. CJ Corona had no reason to inhibit himself from the case. None of the grounds in either the Rules of Court or the Internal Rules of the Supreme Court apply to him in the particular case.

20. Besides, it is not uncommon for Justices to have previously worked as professionals in close association with the President. A number of notable examples are:

| Justices of the Supreme Court | Appointed by President | Position prior to appointment in SC |

| Jose Abad Santos | Quezon | Secretary, DOJ |

| Delfin Jaranilla | Osmena | Secretary, DOJ |

| Jesus G. Barrera | Garcia | Secretary, DOJ |

| Calixto Zaldivar | Macapagal | Asst. Executive Sec then Acting Executive Sec |

| Claudio Teehankee | Marcos | Secretary, DOJ |

| Vicente Abad Santos | Marcos | Secretary, DOJ |

| Enrique Fernando | Marcos | Presidential Legal Counsel |

| Felix V. Makasiar | Marcos | Secretary, DOJ |

| Pedro Yap | Aquino | Commissioner, PCGG |

| Leonardo Quisumbing | Ramos | Secretary, DOLE |

| Antonio Eduardo Nachura | GMA | Presidential Legal Counsel |

21. Incidentally, Justice Antonio Carpio, whom GMA appointed to the Supreme Court, was a partner in the law firm that used to be the retained counsel of her family.

22. None of the above appointees inhibited from the cases involving the policies of the Presidents they previously worked with. Their ties with the appointing power were official. When they took their oaths, they swore to discharge faithfully the duties of their new offices.

23. Long standing is the rule that previous service to the government cannot suffice to cause the inhibition of a justice from hearing cases of the government before the Supreme Court. To compel the Justice to inhibit or recuse amounts to violating his security of tenure and amounts to an attack on the independence of the judiciary. In Vargas v. Rilloraza,[31] the Supreme Court struck down an attempt to forcibly disqualify certain Justices from sitting and voting in government cases for the very reason that they were once employed or held office in the Philipine Government, viz:

But if said section 14 were to be effective, such members of the Court “who held any office or position under the Philippine Executive Commission or under the government called Philippine Republic” would be disqualified from sitting and voting in the instant case, because the accused herein is a person who likewise held an office or position at least under the Philippine Executive Commission. In other words, what the constitution in this respect ordained as a power and a duty to be exercised and fulfilled by said members of the People’s Court Act would prohibit them from exercising and fulfilling. What the constitution directs the section prohibits. A clearer case of repugnancy of fundamental law can hardly be imagined.

For repugnancy to result it is not necessary that there should be an actualremoval of the disqualified Justice from his office for, as above demonstrated, were it not for the challenged section 14 there would have been an uninterrupted continuity in the tenure of the displaced Justice and in his exercise of the powers and fulfillment of the duties appertaining to his office, saving only proper cases or disqualification under Rule 126. What matters here is not only that the Justice affected continue to be a member of the Court and to enjoy the emoluments as well as to exercise the other powers and fulfill the other duties of his office, but that he be left unhampered to exercise all the powers and fulfill all the responsibilities of said office in all cases properly coming before his Court under the constitution, again without prejudice to proper cases of disqualification under Rule 126. Any statute enacted by the legislature which would impede him in this regard, in the words of this Court in In reGuariña, supra, citing Marbury vs. Madison, supra, “simply can not become law. ”

It goes without saying that, whether the matter of disqualification of judicial officers belong to the realm of adjective, or to that of substantive law, whatever modifications, change or innovation the legislature may propose to introduce therein, must not in any way contravene the provisions of the constitution, nor be repugnant to the genius of the governmental system established thereby. The tripartite system, the mutual independence of the three departments — in particular, the independence of the judiciary —, the scheme of checks and balances, are commonplaces in democratic governments like this Republic. No legislation may be allowed which would destroy or tend to destroy any of them.

Under Article VIII, section 2 (4) of the Constitution the Supreme Court may not be deprived of its appellate jurisdiction, among others, over those criminal cases where the penalty may be death or life imprisonment. Pursuant to Article VIII, sections 4, 5, 6, and 9 of the Constitution the jurisdiction of the Supreme Court may only be exercised by the Chief Justice with the consent of the Commission of Appointments, sitting in banc or in division, and in cases like those involving treason they must sit in banc. If according to section 4 of said Article VIII, “the Supreme Court shall be composed” of the Chief Justice and Associate Justices therein referred to, its jurisdiction can only be exercised by it as thus composed. To disqualify any of these constitutional component members of the Court — particularly, as in the instant case, a majority of them — is nothing short of pro tanto depriving the Court itself of its jurisdiction as established by the fundamental law. Disqualification of a judge is a deprivation of his judicial power. (Diehl vs. Crumb, 72 Okl. , 108; 179 Pac. , 44). And if that judge is the one designated by the constitution to exercise the jurisdiction of his court, as is the case with the Justices of this Court, the deprivation of his or their judicial power is equivalent to the deprivation of the judicial power of the court itself. It would seem evident that if the Congress could disqualify members of this Court to take part in the hearing and determination of certain collaboration cases it could extend the disqualification to other cases. The question is not one of degree or reasonableness. It affects the very heart of judicial independence.(Emphasis supplied)

ARTICLE II

Alleged Non-disclosure of Declaration

of Assets, Liabilities, and Networth

1. CJ Corona denies Article II.

2. Complainants allege in pars. 2.2, 2.3, and 2.4 that CJ Corona committed a culpable violation of the Constitution and/or betrayed public trust by failing to disclose his Statement of Assets, Liabilities, and Net Worth (SALN) as the Constitution provides. CJ Corona has no legal duty to disclose his SALN. Complainants have cited none.

3. Actually, what the Constitution provides is that a public officer shall, upon assumption of office and as often as may be required by law, submit a declaration under oath of his assets, liabilities, and net worth. [32]Implementing this policy, R.A. 6713, the Code of Conduct and Ethical Standards for Public Officials and Employees, imposes on public officials the obligation to accomplish and submit declarations under oath of their assets, liabilities, net worth and financial and business interests. [33]

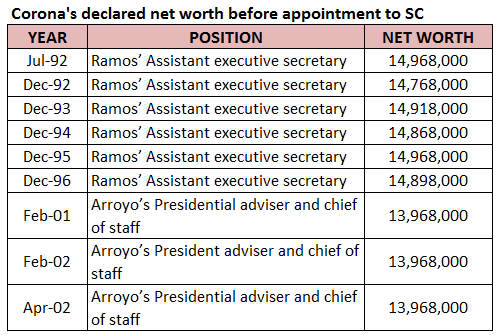

4. Clearly, what the Constitution and the law require is the accomplishment and submission of their SALNs. CJ Corona has faithfully complied with this requirement every year. [34] From that point, it is the Clerk of Court of the Supreme Court who has custody over his declaration of assets, liabilities, and net worth. [35]

5. R.A. 6713 recognizes the public’s right to know the assets, liabilities, net worth and financial and business interests of public officials but subject to limitations provided in Section 8 thereof:

(D) Prohibited acts. – It shall be unlawful for any person to obtain or use any statement filed under this Act for:

a) any purpose contrary to morals or public policy; or

b) any commercial purpose other than by news and communications media for dissemination to the general public.

6. In 1989, Jose Alejandrino, a litigant, requested the Clerk of Court for the SALNs of members of the Supreme Court who took part in the decision that reduced the P2.4 million damages awarded to him by the trial court to only P100,000.00 in a breach of contract case. In an en banc resolution of 2 May 1989, the Supreme Court expressed willingness to have the Clerk of Court furnish copies of the SALNs of the Chief Justice and the Associate Justices to any person upon request, provided there is a legitimate reason for the request, it being in fact unlawful for any person to obtain or use any statement filed under R.A. 6713 for any purpose contrary to morals or public policy, or any commercial purpose other than by news and communications media for dissemination to the general public.

7. Further, the Supreme Court noted that requests for copies of SALNs of justices and judges could endanger, diminish, or destroy their independence and objectivity or expose them to revenge, kidnapping, extortion, blackmail, or other dire fates. For this reason, the Supreme Court resolved in 1989 to lay down the following guidelines for considering requests for the SALNs of justices, judges, and court personnel:

(1) All requests for copies of statements of assets and liabilities shall be filed with the Clerk of Court of the Supreme Court, in the case of any Justice; or with the Court Administrator, in the case of any Judge, and shall state the purpose of the request.

(2) The independence of the Judiciary is constitutionally as important as the right to information which is subject to the limitations provided by law. Under specific circumstances, the need for the fair and just adjudication of litigations may require a court to be wary of deceptive requests for information which shall otherwise be freely available. Where the request is directly or indirectly traced to a litigant, lawyer, or interested party in a case pending before the court, or where the court is reasonably certain that a disputed matter will come before it under circumstances from which it may, also reasonably, be assumed that the request is not made in good faith and for a legitimate purpose, but to fish for information and, with the implicit threat of its disclosure, to influence a decision or to warn the court of the unpleasant consequences of an adverse judgment, the request may be denied. (Emphasis supplied)

(3) Where a decision has just been rendered by a court against the person making the request and the request for information appears to be a “fishing expedition” intended to harass or get back at the Judge, the request may be denied.

(4) In the few areas where there is extortion by rebel elements or where the nature of their work exposes judges to assaults against their personal safety, the request shall not only be denied but should be immediately reported to the military

(5) The reason for the denial shall be given in all cases. [36]

8. The Supreme Court reiterated and strengthened this policy in a resolution three years later. In 1992, the Supreme Court denied the request of a Graft Investigation Officer of the Office of the Ombudsman and a military captain for certified true copies of the sworn statements of the assets, liabilities, and net worth of two judges, it appearing that the intention was “to fish for information” against the judges. [37]

9. At any rate, CJ Corona has not prevented the public disclosure of his declarations of assets, liabilities, and networth. Firstly, it is not for the Chief Justice to unilaterally decide whether to disclose or not to disclose them. Secondly, the release of the SALNs of Justices is regulated by law and the Court’s various Resolutions cited above. Thirdly, CJ Corona never issued an order that forbids the public disclosure of his above declarations.

10. In pars. 2.3 and 2.4, Complainants suspect and accuse CJ Corona of betrayal of public trust because he allegedly accumulated ill-gotten wealth, acquired high-value assets, and kept bank accounts with huge deposits, not declared in his SALN.

11. The allegations are conjectural and speculative. They do not amount to a concrete statement of fact that might require a denial. Accusations in general terms such as these have no place in pleadings, as they bring only hearsay and rumor into the body of evidence involved. At any rate, the allegations are flatly denied. The truth of the matter is that CJ Corona acquired his assets from legitimate sources of income, mostly from his professional toils.

12. Finally, Complainants allege in par. 2.4 that “reports” state CJ Corona acquired a 300-sq. m. apartment in the Fort, Taguig. Complainants speculate that he has not reported this in his SALN and that its price is beyond his income as a public official. CJ Corona admits that he and his wife purchased on installment a 300-sq. m. apartment in Taguig, declared in his SALN when they acquired it.

ARTICLE III

Alleged Lack of Competence, Integrity,

Probity, and Independence

1. CJ Corona denies Article III.

2. Complainants allege in pars. 3.3, 3.3.1, 3.3.2, 3.3.3 and 3.3.4, that CJ Corona allowed the Supreme Court to act on mere letters from a counsel inFlight Attendants and Stewards Association of the Philippines (FASAP) v. Philippine Airlines (PAL),[38] resulting in flip-flopping decisions in the case. Complainants say that the Court did not even require FASAP to comment on those letters of PAL’s counsel, Atty. Estelito Mendoza, betraying CJ Corona’s lack of ethical principles and disdain for fairness.

3. Firstly, lawyers and litigants often write the Supreme Court or the Chief Justice regarding their cases. The Supreme Court uniformly treats all such letters as official communications that it must act on when warranted. The practice is that all letters are endorsed to the proper division or the Supreme Court en banc in which their subject matters are pending. No letter to the Supreme Court is treated in secret.

4. Secondly, CJ Corona took no part in the FASAP Case, having inhibited since 2008.

5. Thirdly, Atty. Mendoza wrote the letters to the Clerk of Court about a perceived mistake in raffling the FASAP Case to the Second Division following the retirement of Justice Nachura. [39] Since the Second Division Justices could not agree on the reassignment of this case, it referred the matter to the Supreme Court en banc pursuant to the Internal Rules.

6. After deliberation, the Supreme Court en banc accepted the referral from the Second Division and proceeded to act on the case. [40] CJ Corona did not take part in the case.

7. Complainants also allege in par. 3.3.3 that the Supreme Court also flip-flopped in its decisions in League of Cities v. COMELEC. [41] It is unfair, however, to impute this to CJ Corona. As stated earlier, the Supreme Court is a collegial body and its actions depend on the consensus among its members. Although the Chief Justice heads that body, he is entitled to only one vote in the fifteen-member Supreme Court.

8. Besides, the changing decisions of the Supreme Court in League of Citiescan hardly be considered as flip-flopping of votes. Justice Roberto A. Abad demonstrated this in his concurring opinion, thus:

One. The Justices did not decide to change their minds on a mere whim. The two sides filed motions for reconsideration in the case and the Justices had no options, considering their divided views, but to perform their duties and vote on the same on the dates the matters came up for resolution.

The Court is no orchestra with its members playing one tune under the baton of a maestro. They bring with them a diversity of views, which is what the Constitution prizes, for it is this diversity that filters out blind or dictated conformity.

Two. Of twenty-three Justices who voted in the case at any of its various stages, twenty Justices stood by their original positions. They never reconsidered their views. Only three did so and not on the same occasion, showing no wholesale change of votes at any time.

Three. To flip-flop means to vote for one proposition at first (take a stand), shift to the opposite proposition upon the second vote (flip), and revert to his first position upon the third (flop). Not one of the twenty-three Justices flipped-flopped in his vote.

Four. The three Justices who changed their votes did not do so in one direction. Justice Velasco changed his vote from a vote to annul to a vote to uphold; Justice Villarama from a vote to uphold to a vote to annul; and Justice Mendoza from a vote to annul to a vote to uphold. Not one of the three flipped-flopped since they never changed their votes again afterwards.

Notably, no one can dispute the right of a judge, acting on a motion for reconsideration, to change his mind regarding the case. The rules are cognizant of the fact that human judges could err and that it would merely be fair and right for them to correct their perceived errors upon a motion for reconsideration. The three Justices who changed their votes had the right to do so.

Five. Evidently, the voting was not a case of massive flip-flopping by the Justices of the Court. Rather, it was a case of tiny shifts in the votes, occasioned by the consistently slender margin that one view held over the other. This reflected the nearly even soundness of the opposing advocacies of the contending sides.

Six. It did not help that in one year alone in 2009, seven Justices retired and were replaced by an equal number. It is such that the resulting change in the combinations of minds produced multiple shifts in the outcomes of the voting. No law or rule requires succeeding Justices to adopt the views of their predecessors. Indeed, preordained conformity is anathema to a democratic system.

9. Complainants allege in pars. 3.4, 3.4.1, 3.4.2, 3.4.3, 3.4.4, 3.4.5, 3.4.6, 3.4.7, 3.4.8, 3.4.9 and 3.4.10 that CJ Corona compromised his independence when his wife accepted an appointment from Mrs. Arroyo to the Board of John Hay Management Corporation (JHMC). JHMC is a wholly-owned subsidiary of Bases Conversion Development Authority (BCDA), a government-owned and controlled corporation. Complainants claim that the appointment of Mrs. Corona was meant to secure CJ Corona’s loyalty and vote in the Supreme Court.

10. The truth of the matter is that Mrs. Corona was named to the JHMC on 19 April 2001, even before CJ Corona joined the Supreme Court. Her appointment did not in any way influence the voting of CJ Corona when he eventually joined the Court. No law prohibits the wife of a Chief Justice from pursuing her own career in the government. This is commonplace. Indeed, Article 73 of the Family Code explicitly allows the wife to exercise any legitimate profession, business, or activity even without the consent of the husband.

11. The Constitution provides that “the State recognizes the role of women in nation-building, and shall ensure the fundamental equality before the law of women and men. ”[42] Further, the State is called on to provide women with “opportunities that will enhance their welfare and enable them to realize their full potential in the service of the nation. ”[43]

12. Complainants allege that complaints have been filed against Mrs. Corona by disgruntled members of the Board of JHMC and certain officers and employees. This is not the forum for hearing and deciding those complaints. Mrs. Corona has adequately answered and is prepared to face her accusers before the appropriate forum. Surely, CJ Corona is not being impeached for alleged offenses of his wife.

13. Complainants also allege that CJ Corona used court funds for personal expenses. Complainants summed this up in their general allegations as “petty graft and corruption for his personal profit and convenience. ”[44]

14. CJ Corona denies these unspecified allegations. They are untrue and unfounded. Complainants are desperate to demonstrate some reason to believe that CJ Corona has committed acts constituting culpable violation of the Constitution, betrayal of public trust, or graft and corruption.

15. Complainants next allege in pars. 3.5. 3.5.2, 3.5.4, 3.5.5, 3.5.6, 3.5.8, 3.5.9, 3.5.10 and 3.5.11 that CJ Corona improperly entertained Lauro Vizconde who had a case pending before the Supreme Court. In truth, only Dante Jimenez, as head of the Volunteers Against Crime and Corruption (VACC) was cleared to make a courtesy call on the newly appointed Chief Justice. CJ Corona was thus surprised to see Lauro Vizconde come into his chambers with Jimenez. It is regrettable that Lauro Vizconde remained during the meeting, rest assured, however, that this is a result of etiquette and manners, and not any evil intention to connive or commit any act in violation of ethical norms.

16. It is not true that CJ Corona told Vizconde and Jimenez that Justice Carpio was lobbying for accused Hubert Webb’s acquittal. Firstly, the Chief Justice had no basis for saying this. Secondly, he does not discuss pending cases with anyone. Thirdly, research will show a report taken from the Philippine News dated 23 February 2011 which says that both CJ Corona and Lauro Vizconde were warned in 2006 by a Court of Appeals Justice about someone lobbying for acquittal in the Hubert Webb case. As CJ Corona recalls it now, it was Jimenez and Vizconde who initiated the discussion complaining about Justice Carpio’s alleged maneuvers in the case.

17. The Complainants resurrect the old charge that Fernando Campos raised against CJ Corona in connection with the Supreme Court’s action in Inter-Petal Recreational Corporation v. Securities and Exchange Commission. [45]Campos claimed that CJ Corona dismissed the case with undue haste, impropriety, and irregularity. Unfortunately, Campos did not say that the Supreme Court dismissed his petition by minute resolution because he erroneously appealed the ruling of the SEC to the Supreme Court instead of the Court of Appeals and because he failed to show that the SEC committed grave abuse of discretion in deciding the case against his company.

18. Complainants are evidently unfamiliar with Supreme Court procedure. The Supreme Court often dismisses unmeritorious cases by minute resolution the first time it is reported and deliberated on, a well-established practice necessitated by the volume of cases the Supreme Court receives every day from all over the country. And although the case has been assigned to CJ Corona as the Member-in-Charge, the Division to which he was assigned fully deliberated on its merits notwithstanding that its action was covered which resulted in a minute resolution.

19. Further, except for saying that he had heard about it, Campos has never been able to substantiate his charge that CJ Corona privately met with the adverse party’s counsel in connection with the case. His allegation is pure hearsay and speculation, hardly a ground for impeachment.

20. True, in refuting Campos’ claim, CJ Corona wrote the Judicial and Bar Council (JBC) stating that it was Campos who pestered him through calls made by different people on his behalf. According to Complainants, this is an admission that various persons were able to communicate with CJ Corona in an attempt to influence him in the case. CJ Corona, they allege, should have taken these people to task for trying to influence a magistrate of the Supreme Court by filing administrative charges against them.

21. No breach of ethical duties, much less an impeachable offense, is committed when a magistrate ignores attempts to influence him.

ARTICLE IV

Alleged Disregard of the Principle of Separation

of Powers In Ombudsman Gutierrez’s case

1. CJ Corona denies Article IV.

2. Complainants allege in pars. 4.2, 4.3 and 4.4, that CJ Corona is responsible for the Supreme Court en banc hastily issuing an SQAO over the impeachment proceedings of Ombudsman Merceditas Gutierrez, revealing his high-handedness and partisanship.

3. The allegation is unfounded.

4. There was no “undue haste. ” Section 2 (c), Rule 11, of the Supreme Court’s Internal Rules authorizes prompt inclusion of a petition in the Supreme Court’s agenda where a party seeks the issuance of a temporary restraining order or writ, viz. :

(c) petitions under Rules 45, 64, and 65 – within ten days, unless a party asks for the issuance of a temporary restraining order or a writ, and the Chief Justice authorizes the holding of a special raffle and the immediate inclusion of the case in the Agenda * * *

5. Complainants rely on Justice Maria Lourdes’s separate opinion that “several members of the Court * * had not yet then received a copy of the Petition,”[46] hence, no genuinely informed debate could be had.

6. The Internal Rules of the Supreme Court do not require copies to be furnished to all members when the petition has been identified as urgent. Section 6 (d), Rule 7 of the Internal Rules of Court merely provide that copies of urgent petitions are furnished to the Member-in-Charge and the Chief Justice, viz. :

SEC. 6. Special raffle of cases. – Should an initiatory pleading pray for the issuance of a temporary restraining order or an urgent and extraordinary writ such as the writ of habeas corpus or of amparo, and the case cannot be included in the regular raffle, the Clerk of Court shall immediately call the attention of the Chief Justice or, in the latter’s absence, the most senior Member of the Court present. The Chief Justice or the Senior Member of the Court may direct the conduct of a special raffle, in accordance with the following procedure:

* * *

(d) The Clerk of Court shall furnish the Member-in-Charge to whom the case is raffled, the Judicial Records Office, and the Rollo Room at the Office of the Chief Justice, copies of the result of the special raffle in an envelope marked “RUSH. ” The Member-in-Charge shall also be furnished a copy of the pleading. If the case is classified as a Division case, the Clerk of Court shall furnish the same copies to the Office of the Clerk of Court of the Division to which the same Member-in-Charge belongs and to the Division Chairperson.

7. Although some Justices may not have received copies of the petition, the Member-in-Charge of the case prepared and furnished the other Justices copies of a detailed report on the petition and recommending the issuance of a TRO. This reporting of cases is a practice provided for in the Supreme Court’s Internal Rules. Sections 3 (a), (b), and (c) make reference to reports by a Member-in-Charge, viz. :

SEC. 3. Actions and decisions, how reached. – The actions and decisions of the Court whether en banc or through a Division, shall be arrived at as follows:

(a) Initial action on the petition or complaint. – After a petition or complaint has been placed on the agenda for the first time, the Member-in-Charge shall, except in urgent cases, submit to the other Members at least three days before the initial deliberation in such case, a summary of facts, the issue or issues involved, and the arguments that the petitioner presents in support of his or her case. The Court shall, in consultation with its Members, decide on what action it will take.

(b) Action on incidents. – The Member-in-Charge shall recommend to the Court the action to be taken on any incident during the pendency of the case.

(c) Decision or Resolution. – When a case is submitted for decision or resolution, the Member-in-Charge shall have the same placed in the agenda of the Court for deliberation. He or she shall submit to the other Members of the Court, at least seven days in advance, a report that shall contain the facts, the issue or issues involved, the arguments of the contending parties, and the laws and jurisprudence that can aid the Court in deciding or resolving the case. In consultation, the Members of the Court shall agree on the conclusion or conclusions in the case, unless the said Member requests a continuance and the Court grants it.

8. The Justices deliberated the case at length. Only after every one who wanted to speak had done so did the Justices agree to take a vote. It was at this point that the Supreme Court issued the SQAO.

9. Although a Member-in-Charge is authorized by the Rules of Court to issue the preliminary injunction on his own, [47] this has never been the practice in the Supreme Court.

10. Complainants allege that, in issuing the SQAO, the Supreme Court headed by CJ Corona violated the principle of separation of powers. This principle is not absolute. The Constitution precisely grants the Supreme Court the power to determine whether the House of Representatives gravely abused its discretion amounting to lack of jurisdiction in the exercise of its functions. Precisely, section 1 of Article VIII of the 1987 Constitution provides:

Section 1. The judicial power shall be vested in one Supreme Court and in such lower courts as may be established by law. Judicial power includes the duty of the courts of justice to settle actual controversies involving rights which are legally demandable and enforceable, and to determine whether or not there has been a grave abuse of discretion amounting to lack or excess jurisdiction on the part of any branch or instrumentality of the Government. (Emphasis supplied. )

11. The Gutierrez petition posed a significant constitutional issue: whether the ban against more than one impeachment complaint within a year provided in Section 3 (5), Article XI of the Constitution had been violated. The Supreme Court issued the SQAO to prevent the petition from being rendered moot and academic.

12. Actually, this is not a novel issue. In Francisco v. House of Representatives[48] the Supreme Court reviewed compliance with Constitutional procedure in impeachment proceedings. Thus, CJ Corona cannot be held liable for actions of the Supreme Court.

ARTICLE V

Alleged Disregard of Principle of Res Judicata

By Reviving Final and Executory Decisions

1. CJ Corona denies Article V.

2. Complainants allege in pars. 5.3, 5.4, 5.5, 5.6, 5.7, 5.8, 5.9, 5.10, 5.11, 5.12, 5.13, 5.14, 5.15, and 5.16 that CJ Corona failed to maintain the principle of immutability of final judgments in three cases: League of Cities v. COMELEC,[49] Navarro v. Ermita,[50] and FASAP v. Philippine Air Lines. [51]The succeeding discussion will demonstrate that these allegations are false and misleading.

3. The League of Cities Case has been decided by the Supreme Court with finality. For this reason, Complainants cannot have this Impeachment Court review the correctness of this decision without encroaching on the judicial power of the Supreme Court. As earlier argued, Maglasang v. People[52]states the rule that no branch of government may pass upon judgments of the Supreme Court or declare them unjust. [53]

4. The above principle dictates that grounds for impeachment cannot involve questions on the correctness of decisions of the Supreme Court.

5. Complainants fault CJ Corona for entertaining prohibited pleadings such as the letters to the Chief Justice in the League of Cities Case. These letters were received on 19 January 2009, more than a year before CJ Corona assumed office. Besides, CJ Corona was merely furnished copies of the letters as an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court.

6. The letters merely requested the participation of the Justices who previously took no part in the case. They were treated as motions upon which the opposing party was required to comment.

7. CJ Corona never flip-flopped on his votes, voting consistently, in favor of the constitutionality of the sixteen (16) Cityhood Laws.

8. The letters did not bring about a flip-flop in the case. In fact, the Resolutions of the Supreme Court dated 31 March 2009 and 28 April 2009, upheld the earlier Decision of 18 November 2008.

9. Contrary to the allegation in the Complaint, the decision of 18 November 2008 did not attain finality on 21 May 2009. The entry of judgment made on said date was recalled by the Supreme Court.

10. The recall of entries of judgment, while extraordinary, is not novel. The Supreme Court has issued such resolutions in cases, under specified and narrow limits, such as Gunay v. Court of Appeals;[54] Manotok v. Barque;[55]Advincula v. Intermediate Appellate Court;[56] and People v. Chavez. [57]

11. Because the Entry of Judgment of 21 May 2011 was premature, the Decision of 18 November 2008 did not attain finality and the principle of res judicata cannot apply. Indeed, the second motion for reconsideration filed by the respondents was declared not a prohibited pleading in a Resolution dated 2 June 2009 penned by Justice Antonio T. Carpio, thus:

As a rule, a second motion for reconsideration is a prohibited pleading pursuant to Section 2, Rule 52 of the Rules of Civil Procedure which provides that: “No second motion for reconsideration of a judgment or final resolution by the same party shall be entertained. ” Thus, a decision becomes final and executory after 15 days from receipt of the denial of the first motion for reconsideration.

However, when a motion for leave to file and admit a second motion for reconsideration is granted by the Court, the Court therefore allows the filing of the second motion for reconsideration. In such a case, the second motion for reconsideration is no longer a prohibited pleading.

In the present case, the Court voted on the second motion for reconsideration filed by respondent cities. In effect, the Court allowed the filing of the second motion for reconsideration. Thus, the second motion for reconsideration was no longer a prohibited pleading. However, for lack of the required number of votes to overturn the 18 November 2008 Decision and 31 March 2009 Resolution, the Court denied the second motion for reconsideration in its 28 April 2009 Resolution. [58] (Emphasis supplied)

11. Second motions for reconsideration have been allowed for the purpose of rectifying error in the past, see for reference, Ocampo v. Bibat-Palamos;[59]Sta. Rosa Realty v. Amante;[60] Millares v. NLRC;[61] Soria v. Villegas;[62] Uy v. Land Bank of the Philippines;[63] Manotok v. Barque;[64] Galman v. Sandiganbayan;[65]and In re: Republic v. Co Keng. [66]

12. According to Poliand v. National Development Company,[67] a subsequent motion for reconsideration is not a second motion for reconsideration if it seeks the review of a new resolution which “delves for the first time” on a certain issue:

Ordinarily, no second motion for reconsideration of a judgment or final resolution by the same party shall be entertained. Essentially, however, the instant motion is not a second motion for reconsideration since the viablerelief it seeks calls for the review, not of the Decision dated August 22, 2005, but the November 23, 2005 Resolution which delved for the first time on the issue of the reckoning date of the computation of interest. In resolving the instant motion, the Court will be reverting to the Decision dated August 22, 2005. In so doing, the Court will be shunning further delay so as to ensure that finis is written to this controversy and the adjudication of this case attains finality at the earliest possible time as it should. ” (Emphasis supplied)

13. Based on Poliand, the subsequent pleadings filed by the respondents were not second, third or fourth motions for reconsideration.

14. Thus, CJ Corona may not be held liable due to the granting of a second motion for reconsideration as this would amount to an unwarranted review of a collegial action of the Supreme Court. [68]

15. The other two cases—Navarro and FASAP—have not yet been decided with finality since they are still subject of unresolved motions for reconsideration. Consequently, it would be inappropriate and unethical for the Chief Justice to dwell on their merits in this Answer.

16. Besides, it would also be unfair, improper, and premature for the Impeachment Court to discuss the merits of these two cases since such could very well influence the result of the case pending with the Supreme Court. At any rate, if the Impeachment Court decides to look into these two cases, then it may have to give the parties to the case the opportunity to be heard. This would amount to an attempt to exercise judicial power.

17. For the above reasons, CJ Corona cannot make any comment on theNavarro and FASAP Cases, for he would be required to take a stand on the issues. It will be recalled that he inhibited in FASAP. In Navarro, he is likewise prohibited from making any comment as it is still sub-judice.

ARTICLE VI

Alleged Improper Creation of the

Supreme Court Ethics Committee

1. CJ Corona denies Article VI.

2. Complainants allege in pars. 6.3, 6.4, and 6.5 that CJ Corona betrayed public trust when “he created” the Supreme Court’s Ethics Committee purposely to investigate and exonerate Justice Mariano C. Del Castillo, theponente in Vinuya v. Executive Secretary[69] who was charged with plagiarism. Allegedly, the CJ encroached on the power of the House to impeach and of the Senate to try the Justices of the Supreme Court.

3. The truth of the matter is that, CJ Corona did not create the Ethics Committee. It was the Supreme Court en banc, during the tenure of Chief Justice S. Reynato Puno, that unanimously approved A.M. No. 10-4-20-SC,[70]creating the Ethics Committee. Rule 2, Section 13 of the Internal Rules provide:

SEC. 13. Ethics Committee. – In addition to the above, a permanent Committee on Ethics and Ethical Standards shall be established and chaired by the Chief Justice, with the following membership:

(a) a working Vice-Chair appointed by the Chief Justice;

(b) three (3) members chosen among themselves by the en banc by secret vote; and

(c) a retired Supreme Court Justice chosen by the chief Justice as a non-voting observer-consultant.

The Vice-Chair, the Members and the retired Supreme Court Justice shall serve for a term of one (1) year, with the election in case of elected Members to be held at the call of the Chief Justice. [71]

* * *

4. The Supreme Court’s Internal Rules provide that the Ethics Committee “shall have the task of preliminarily investigating all Complaints involving graft and corruption and violation of ethical standards, including anonymous Complaints, filed against Members of the Supreme Court, and of submitting findings and recommendations to the Supreme Court en banc. ”[72]

5. Since the Supreme Court approved its Internal Rules that created the Ethics Committee long before Justice Del Castillo was charged with plagiarism, it cannot be said that CJ Corona created the Committee purposely to exonerate him.

6. Contrary to Complainants’ claim, it was the Supreme Court en banc that referred his case to the Ethics Committee. [73] Notably, the members of the Ethics Committee were elected through secret balloting by the members of the Supreme Court en banc.

7. After hearing the parties on their evidence, the Ethics Committee[74]unanimously recommended to the Supreme Court en banc the dismissal of the charge of plagiarism against Justice Del Castillo. The Supreme Court en banc absolved him on a 10-2 vote,[75] and subsequently voted 11-3 to deny the motion for reconsideration filed in the case. [76] CJ Corona cast but one vote in both instances with the majority.

8. The creation of the Ethics Committee by the Supreme Court cannot be regarded as an act of betrayal of public trust. The power to promulgate Internal Rules and create the Ethics Committee stems from the power of the Supreme Court to discipline its own members as provided for in Section 6 Article VIII of the 1987 Constitution. [77]

9. The Committee’s power is only recommendatory. If the offense is impeachable, the Supreme Court en banc will refer the matter to the House of Representatives for investigation. On the other hand, if the offense is non-impeachable, the Supreme Court en banc may decide the case and, if warranted, impose administrative sanctions against the offender.

10. Actually, disciplining members of the Supreme Court is not a new development. The Supreme Court en banc investigated then censured Associate Justice Fidel Purisima in 2002 for failing to disclose on time his relationship to a bar examinee and for breach of duty and confidence. The Supreme Court also forfeited fifty percent of the fee due him as Chairman of the 1999 Bar Examinations Committee. [78]

11. In 2003, the Supreme Court en banc empowered a committee consisting of some of its members to investigate Justice Jose C. Vitug as a possible source of leakage in the 2003 bar exams in Mercantile Law. The Supreme Court eventually absolved Justice Vitug of any liability for that leakage. [79]

12. Lastly, on 24 February 2008 the Supreme Court en banc created a committee to investigate the charge that Justice Ruben Reyes leaked a confidential internal document of the Supreme Court to one of the parties to a case pending before it. The Supreme Court, acting on the findings of the committee, found Justice Reyes guilty of grave misconduct, imposed on him a fine of P500,000.00 and disqualified him from holding any office or employment in the government. [80]

ARTICLE VII

Alleged Improper Issuance of TRO to Allow

President GMA and Husband to Flee the Country

1. CJ Corona denies Article VII.

2. Complainants allege in pars. 7.1, 7.2, 7.3, 7.4, 7.5, 7.7, 7.8, 7.9, and 7.10 that the Supreme Court under CJ Corona inexplicably consolidated the separate petitions of GMA and her husband Jose Miguel Arroyo to give undue advantage to the latter, since the urgent health needs of GMA would then be extended to him.

3. The consolidation of actions has always been addressed to the sound discretion of the court where they have been filed. Section 1 of Rule 31 provides that when actions involving a common question of law or fact are pending before the court, it may order the actions consolidated. The Supreme Court’s own Internal Rules[81] provide for in Section 5, Rule 9, consolidation in proper cases, thus:

SEC. 5. Consolidation of cases. – The Court may order the consolidation of cases involving common questions of law or of fact.

4. In the Arroyo petitions, the Supreme Court en banc unanimously ordered the consolidation of their petitions since they involved common questions of fact and law. In both petitions, the principal issue is whether the Secretary of Justice has violated their Constitutional right to travel by issuing a WLO, preventing them from leaving the country.

5. Once more, the consolidation was a unanimous collegial action of the Supreme Court en banc. It would be unfair to subject CJ Corona to impeachment for consolidating these petitions, without impleading all the members of the Supreme Court.

6. Complainants allege in par. 7.2 that the Supreme Court under CJ Corona hastily granted the TRO to allow GMA and her husband to leave the country despite certain inconsistencies in the petition and doubts regarding the state of her health. Further, Complainants assail par. 7.3 the propriety of the issuance of the TRO, despite the Member-in-Charge’s recommendation to hold a hearing first.

7. The Supreme Court en banc did not act with undue haste. The members were given copies of the petitions of GMA and her husband. The deliberation on the matter took long because many of the Justices presented their separate views. Only then did the Justices decide to submit the matter to a vote. The majority opted to issue a TRO, enjoining the Secretary of Justice from enforcing her WLO against the Arroyos.

8. Complainants lament that the Supreme Court en banc acted on the applications for TRO despite the Member-in-Charge’s recommendation that the en banc first hold a hearing on the matter. But, firstly, the Supreme Courten banc is not bound by the Member-in-Charge’s recommendation. As in any collegial body, the decision of the majority prevails, consistent with democratic processes, over the opposite view of the minority.

9. Significantly, the Office Solicitor General (OSG) filed separate manifestations and motions in the two cases, seeking deferment of court action on the applications for the TRO. If these were not granted, the OSG alternatively asked the Supreme Court to consider the arguments presented in those manifestations and motions as its opposition to the TRO. The Supreme Court en banc did so. Consequently, Complainants cann