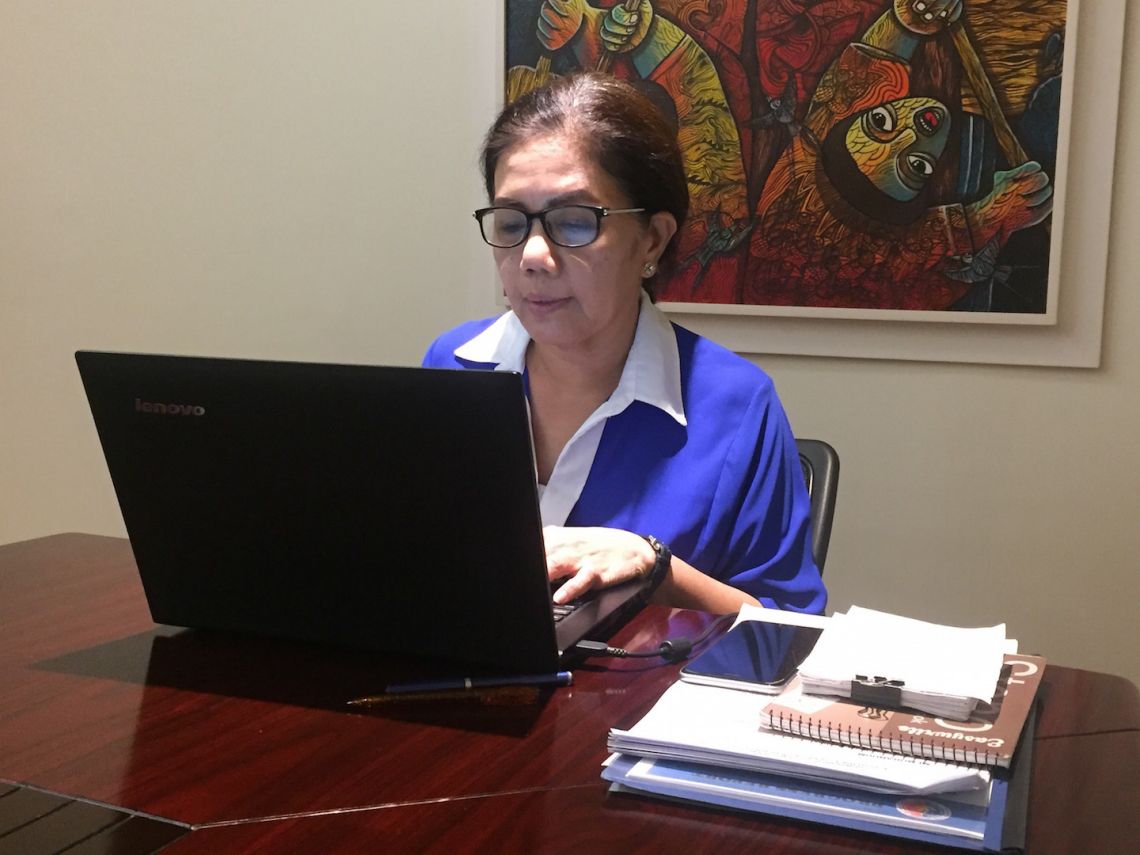

Retired two-star police general Lina Sarmiento, who chairs the HRVCB, is confident that the board will finish the reparation process for martial law victims before May 2018.

While the 45th anniversary of the declaration of martial law on Sept. 21 might be remembered for the various protest actions it sparked nationwide, the same day marked a quiet but equally momentous development for victims of human rights violations during the Marcos dictatorship.

The Human Rights Victims’ Claims Board (HRVCB), the agency in charge of martial law reparations, released on Thursday a list of 2,035 more victims eligible for compensation.

The 35-page list of eligible claimants is posted on the HRVCB website and Facebook page, and will be published in local tabloids Remate and Balita on Sept. 28 and Oct. 5.

Some P155 million from P10 billion of the Marcos’ ill-gotten wealth, in the form of Swiss bank accounts deposits forfeited to the Philippine government in 1997, will be divided among the claimants and issued through cash cards at the Landbank of the Philippines.

In April, the HRVCB had released P300 million worth of partial compensation to an initial 4,000 approved claimants.

Under Republic Act No. 10368, the HRVCB is tasked to recognize and compensate victims of summary execution, torture, enforced or involuntary disappearance and other human rights violations committed during the Marcos regime.

Of more than 2,000 claimants in the second tranche, 382 are declared “conclusively presumed,” or those who were among the 10,000 rights victims who filed a class suit against Marcos in Hawaii, more popularly known as the “Hawaii claimants.” The rest are considered “new applicants.”

Claims board chief Lina Sarmiento told VERA Files the HRVCB is expected to release the third and final list of approved claimants before year-end.

Under pressure to complete the reparation process by May 2018, Sarmiento said she is confident the board will finish the task, trusting in the commitment of her colleagues in the nine-member board en banc, some of whom are martial law victims, and are “stakeholders” themselves.

She sees no need for another deadline extension, saying the victims “have long been waiting” for closure.

“For those who were really affected, those who experienced (human rights violations) and their family members, how could they forget? You will not forget,” Sarmiento, a retired two-star police general, said.

Created in 2014, the HRVCB was initially given until May 2016 to complete the reparation process. It was granted a two-year extension due to the massive volume of claims, 75,730 in total. This is almost four times than the expected 20,000, which is double the number of Hawaii claimants.

As of Sept. 8, the HRVCB has processed 75 percent of the claims, leaving a backlog of 19,305, or at least 344 cases for each of its 56 legal assistants to work on.

Legal assistants at the HRVCB work double time to turn in all case resolutions of compensation claims before the board’s deadline.

Asked if she thinks the workload for each employee is manageable, Sarmiento said the HRVCB sees the need to hire more legal assistants for the homestretch.

Supervised by 31 lawyers, the legal assistants are tasked to sift through and check for completeness in affidavits and documentary evidence submitted by claimants, as well as draft a preliminary decision on whether to approve or reject the claim.

Yet, even as the HRVCB is nearing its target, it is delayed by fraudulent claims, as well as appeals from the first batch of approved claimants. (See VERA FILES FACT SHEET: The sins of martial law, in tranches)

An example Sarmiento cited was one claimant who filed for torture and killing, when in fact the claimant is alive. “How can you file for a killing when you’re alive?” the claims board chief asked.

Another inconsistent claim, less deliberate than the first, was from one claimant who purported to be the sole heir of a human rights victim, but whose birth certificate shows he is the seventh child.

Appeals and oppositions are also coming in, mostly from the kin of human rights victims who assert their right to a share in the compensation.

The law allows aggrieved claimants to file within the HRVCB en banc an appeal within 10 days from receipt of the resolution. As of writing, the board has 62 appeals and 20 oppositions to deliberate on.

For instance, a case of a victim of killing whose siblings filed for reparations to have him buried in a cemetery because the family cannot afford a lot. Yet, when the money was released, the family member who was given compensation reneged on the plan.

“It’s sad because this is not about the money. This is more of an acknowledgment of what happened in the past, an acknowledgement of the sufferings they experienced. But then, you’ll see, those who are left behind are fighting,” said Sarmiento.