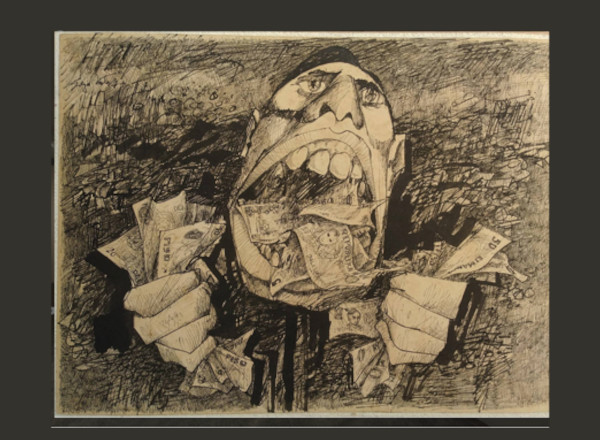

The period Sept. 21, 1972 to Feb. 25, 1986 — between when Ferdinand Marcos declared martial law and when he fled the country — has resulted in what the law describes as many “deaths, injuries, sufferings, deprivations and damages.”

Republic Act No. 10368, enacted in 2013, has committed the state to compensate those who suffered human rights violations, including summary executions, torture and enforced disappearances, under the Marcos dictatorship.

Some P10 billion has been allocated for the reparations, drawn from the Marcoses’ ill-gotten wealth, in the form of Swiss bank accounts deposits forfeited in favor of the Philippine government in 1997.

Tasked with processing the claims is the Human Rights Victims’ Claims Board (HRVCB), an independent agency created by R.A. No. 10368.

Originally given until May 12, 2016 to finish the reparations, the HRVCB was given a two-year extension, until 2018, to cope with the volume of claims.

How is the board faring?

Here are three facts on the monumental challenges the HRVCB faces.

Number of claimants exceeds earlier estimates

Framers of R.A. No. 10368 had estimated 20,000 claimants. They based the figure on the number the human rights victims that filed a class suit with the United States District Court in Hawaii — a total of 10,000 victims more popularly known as the “Hawaii claimants” — and doubled it.

The number of actual claimants, which has reached 75,730, greatly exceeds the earlier estimate, however. This is the reason the claims processing period was extended.

Academic Alfred McCoy, in his famous paper, “Dark Legacy: Human Rights under the Marcos Regime,” provides a much higher number of human rights victims under Marcos: 3,257 killed, 35,000 tortured and 70,000 incarcerated.

As of Sept. 8, the HRVCB has processed 56,425 or three-fourths of compensation claims.

Appeals and bogus claims complicate the process

Complicating the job of the board is the influx of appeals and oppositions to its list of approved claimants, as well bogus claims.

As of writing, the board is looking into 62 appeals and 20 oppositions, mostly of heirs of human rights victims asserting their right for a share in the compensation.

In determining the reparation amounts, the board follows a point system: 10 points for killings and enforced disappearances, six to nine points for torture or rape, three to five for illegal detention, and one to two for other human rights violations.

In May, the board released P300 million to be divided among 4,000 eligible claimants under President Rodrigo Duterte’s order to fast-track the release of reparations. A total of 2,035 claimants were approved Sept. 21.

Weeding out dubious claims also proves a daunting task for HRVCB.

The board does intensive historical research to determine actual human rights victims, cross-referencing claims with consolidated data from “contemporaneous evidence” such as news clippings and release papers of martial law victims submitted by other claimants.

In cases where the board suspects fraud, it asks the claimant to submit additional documentary evidence.

A claim is denied if there is lack of substantial evidence or is considered “patently unmeritorious” if it is lacking in detail.

More personnel needed to get the job done

At present, the HRVCB has only 56 legal assistants who sift through the claims, deliberate on their documentary completeness, and initially decide on the merits of each, subject to the approval of the board.

They are supervised by 31 lawyers, who assign each legal assistant 344 cases to work on and complete before the board’s self-imposed deadline of December 2017, so it can allot the succeeding six months until May 2018 to disbursing payments.

If the board fails to meet the deadline set by law, the reparations fund would stay within the Bureau of Treasury.

Sources:

Claims of martial law victims processed

Mccoy, Alfred. (2001). “Dark Legacy: Human Rights under the Marcos Regime”

Mga madalas na katanungan hinggil sa Republic Act No. 10368

Republic Act No. 10368 or the Human Rights Victims Reparation and Recognition Act of 2013

Interview with HRVCB chair Lina Sarmiento

— Maria Feona Imperial

(Guided by the code of principles of the International Fact-Checking Network at Poynter, VERA Files tracks the false claims, flip-flops, misleading statements of public officials and figures, and debunks them with factual evidence. Find out more about this initiative.)