There is something oddly appropriate about relatives of President Ferdinand “Bongbong” Marcos Jr.—namely his cousin, Philippine ambassador to the United States Jose Manuel Romualdez and his sister, Sen. Imee Marcos—expressing concern about their undocumented countrymen being deported from the US under another Trump presidency, given that the American government once wanted a US-based Bongbong to return to his homeland following, of all things, a traffic violation.

In his congratulatory message to US president-elect Donald Trump, President Ferdinand “Bongbong” Marcos Jr. said he had “personally met President Trump as a young man, so [he knows] that his robust leadership will result in a better future for all of us.” When that meeting happened is unclear, but Bongbong was definitely based in the US twice between his 20s and early 30s. He was there, in exile, with most of the members of his family after the EDSA Revolution; he met his wife-to-be Liza Araneta in New York City, where she worked as a lawyer, while his mother, Imelda Marcos, was on trial there for bank fraud and racketeering. He was in the courtroom when Imelda was acquitted.

Even earlier, between late 1979 and the early 1980s, Bongbong was also based in the US, being a student at Trump’s alma mater, the Wharton School in the University of Pennsylvania. While in the US at that time, he lived in a house in Cherry Hill, Camden County, New Jersey—about a 20-25-minute drive from Wharton—purchased, with international banker and former American Chamber of Commerce of the Philippines head Tristan Beplat as ostensible owner, and maintained using the Marcoses’ ill-gotten wealth.

When his mother was in town—on official business, or for her state-funded shopping sprees—she preferred staying at the Waldorf Towers in New York City. As Bongbong relayed during his first visit to the US as president on September 19, 2022, he would travel through the New Jersey Turnpike when he visited New York from Cherry Hill at that time.

Bongbong’s statement calls to mind these overseas dealings of the Marcoses a few years before the ouster of Ferdinand Sr. It also makes one think about how little Bongbong has publicly said about that time in his life. His profile in his official website simply says that after his time in Oxford University (1975-1978), he “subsequently enrolled at the Wharton School of Business for a Master of Business Administration. It says his stay in Wharton was eventually cut short after he was elected in 1980 as Vice Governor of his home province, Ilocos Norte”—a factual error, as records and news accounts show he was apparently in the US for most of 1980 until about early 1982.

So, what exactly did young Bongbong do in the US during that time (most of 1980 until about early 1982)?

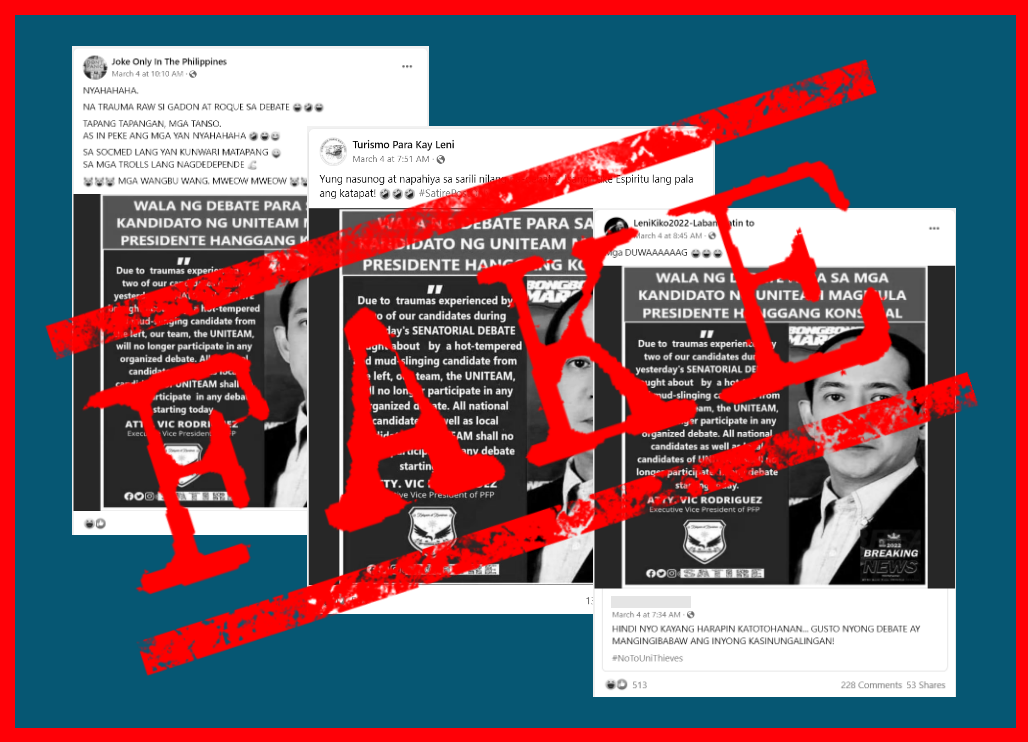

Forty-two years ago, a well-syndicated story from the Los Angeles Times-Washington Post News Service brought to light an incident that is intriguing, to say the least—criminal, to be more accurate—involving a twentysomething US-based Bongbong. Looking back at the incident and the circumstances connected to it highlights how little Bongbong has publicly disclosed about his activities during his father’s dictatorship.

The story was first published by the Los Angeles Times under the title “Accused Korean Diplomat Gives Protocol a Workout” on November 15, 1982. Written by Doyle McManus, the article focused on Nam Chol Oh, a member of the North Korean observer group at the United Nations, who had been accused of attempting to rape an American woman at a park in New York State. Though a warrant for Oh’s arrest had been issued, diplomatic immunity shielded him from American authorities as long as he holed up inside the apartment where the North Korean mission maintained their offices and residences. The delegation refused to surrender Oh to the police. McManus gave a few other instances of foreigners abusing diplomatic immunity, including “the son of the president of the Philippines.”

Guns found in Bongbong’s car

According to McManus, in 1981,

“Ferdinand Marcos Jr….was stopped on the New Jersey Turnpike for driving well over the speed limit. The state trooper who pulled over young Marcos, a student at the University of Pennsylvania, was startled to see a semiautomatic rifle on the back seat and a revolver strapped to the leg of the young woman in the passenger seat.

“Marcos showed a diplomatic passport and the trooper waved him on. ‘Standard procedure,’ said the spokesman for the New Jersey State Police.

“Except, the State Department says, that young Marcos was not registered as a diplomatic agent of his country. He did not really have diplomatic immunity — just a foolproof way to beat a speeding ticket.”

Engagement with Belgian model

The identity of the “young woman” has not been disclosed. Earlier that year, in April, the Agence France-Presse, in articles published in newspapers such as the South China Morning Post and the Straits Times, reported that Bongbong was engaged to marry a Belgian model named Dominique Misson-Peltzer, as announced by her family. The South China Morning Post version of the story said that she was the daughter of a retired lieutenant-colonel, and that she and Bongbong met 18 months prior, or around November 1979, a few months after Bongbong started attending Wharton.

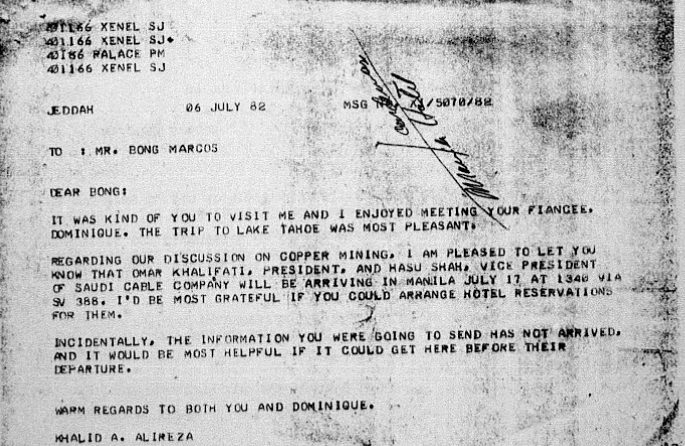

In a May 1981 issue of Asiaweek, Ferdinand Sr. said that the engagement was untrue. Quoting his son, he told Asiaweek that Bongbong “has no plans to marry anybody right now,” but confirmed that Ferdinand Jr. “dated the girl.” But a July 1982 communication from Saudi Arabian businessman Khalid A. Alireza to Bongbong—among the digitized files of the Presidential Commission on Good Government (PCGG)—mentions Marcos Jr.’s “fiancée, Dominique,” and a trip to Lake Tahoe they apparently all took together.

At least five other newspapers in the US carried McManus’s article. The Marcos crony-controlled press in the Philippines likely did not say anything about the revelation that Bongbong had a brush with the law in the US. However, readers of the opposition-aligned We Forum, specifically the newspaper’s November 26-28 issue, were treated to the entire section on Bongbong in McManus’s article through a column by publisher Jose Burgos.

In his article, titled “An Interesting Item on ‘Bongbong’ Marcos,” Burgos explained that that tidbit about Bongbong came from an LA Times clipping that he received two weeks after it was published. Burgos did not make any further comment on Bongbong’s New Jersey incident; if he had intended to do a follow up investigation, he would not have had an outlet to publish his findings, as We Forum was shut down on December 7, 1982 for publishing articles that supposedly discredited, insulted, or ridiculed the president “to such an extent that it would inspire his assassination.” Chief among these were the serialized version of a story on Ferdinand Sr.’s fake wartime heroism and medals, which was written by Bonifacio Gillego. We Forum resumed publication only in January 1985.

Even if news about Bongbong being pulled over in the US reached Philippine shores, it seems that nobody here thought to make much of it. It was probably not surprising to anyone in the Philippines that the extremely privileged son of the dictator violated traffic laws abroad with impunity. Perhaps indicative of the opinion on Bongbong at the time is this excerpt from a declassified airgram from the United States Consulate in Cebu, subject “Students in Cebu: Non-Revolutionary Critics of the New Society,” dated June 27, 1979:

“Perhaps the sharpest criticism is aimed at Ferdinand Marcos, Jr. (Bongbong), who is widely seen by Cebuano students as being groomed by the President to be his successor. It is common to hear comments among students in Cebu about the ‘Marcos Dynasty’. Bongbong’s recent brief tour of duty with the Philippine Army, his immediate designation as a second lieutenant, the special award bestowed on him by the Philippine Military Academy, his earlier appointment as a ‘Special Assistant’ to his father, and his receiving a ‘special diploma’ from Oxford — suggesting incomplete studies — all provide opportunities for sharp criticism and sarcastic comments.”

Though he received a “Special Diploma in Social Studies” from Oxford University, he was able to enter the Master of Business Administration program at Wharton. As explained in a VERA Files article published in 2021, it was through the intervention of Filipino diplomats and business connections that Bongbong started studying at Wharton in August 1979. He was expected to finish his studies between 1980-1981, even after he was elected vice governor of Ilocos Norte in January 1980.

Being a (non-functional) local elected official would not have automatically conferred upon him diplomatic immunity. Being an attaché to the Philippine Mission to the United Nations—which was from 1979-1980—did. It is possible that Bongbong flashed an expired diplomatic passport, acquired from the time he was purportedly a “military adviser” to the Philippine UN Mission, in front of the officer that pulled him over in 1981.

When, exactly, did the incident happen? The exact date can be found in a declassified US Department of State cable, with the subject “Weekly Status Report – Philippines,” dated August 19, 1981. Item number one in the cable is the arrival of first lady Imelda Marcos in the US on August 14. The cable noted that she was apparently seeking appointments with Vice President George H.W. Bush and Secretary of State Alexander Haig, but at that time, “she and her entourage are still essentially on their own vacation in New York and have done very little except in a social way since arrival.” The second item is titled “Marcos’ Son to the West Indies.” The item is reproduced here in full:

“Ferdinand (“Bong Bong”) Marcos, Jr. left New York August 18 for a visit of unknown duration to the island of Guadeloupe in the West Indies. Bong Bong has had discussions with his father and, presumably, with his mother since her arrival in New York in the wake of the August 12 New Jersey Turnpike episode” (emphasis added).

This information was attributed to James Nach of the US Embassy in Manila’s political section. The cable, sent by US state department Country Director for Philippine Affairs Frazier Meade, was addressed to John Holdridge, Assistant Secretary of State of East Asian and Pacific Affairs. At the time, the US did not have an ambassador to the Philippines; days before the turnpike incident, on August 5, 1981, Ambassador Richard Murphy bade goodbye to Ferdinand Sr. at Malacañang.

The son ‘was a problem’

The next US ambassador, Michael Armacost, started his tenure in March 1982. According to a 1999 interview with him by the Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training,

“My initial contacts with him [Ferdinand Sr.] as ambassador were a little rocky. The first instruction—or one of my earliest—was to go to see Marcos to tell him that his son was a problem. He had been arrested for speeding on one of the interstates in the East while working in the United States. The police also found contraband—drugs or guns—in the car. The officials in the States (United States) were obviously not interested in publicizing this event; on the other hand, they could not let the matter go unnoticed. So, I had to go see the father to ask that he bring his son home. That was not a pleasant task under any circumstances; it was particularly unhelpful as a new ambassador’s first act.”

If his recollection was correct, then Bongbong was still based in the US seven months after the turnpike incident, and he was apparently “a problem” not only because of a speeding violation.

What was Bongbong still doing in the US at that time? His Wharton transcript indicates that he last enrolled at the school during the fall term (around August-December) of 1981, though he did not earn any course credits. That meant that he was not a student anymore in 1982. Jose Burgos, in his column for We Forum’s November 29-30, 1982 issue, noted that Bongbong became acting governor of Ilocos Norte that month, after the incumbent governor, his aunt Elizabeth Marcos-Keon, went on “indefinite sick leave”; Bongbong would succeed his aunt as governor about four months later. What he was preoccupied with between December 1981 and November 1982 remains unclear.

US investigates flow of guns through diplomatic channels

Another news item, an exclusive of Camden, New Jersey’s Courier-Post, both provides a possible explanation for the guns he was found with when he was pulled over in August 1981 and what he may have been involved in before he became primarily based in the Philippines again in late 1982. Written by the Courier-Post‘s Bob Collins, the August 2, 1982 article noted that the US was investigating “the flow of American-made weapons out of the country through diplomatic channels,” which involved at least two residents in Cherry Hill, New Jersey.

“The Cherry Hill men are bodyguards to Ferdinand ‘Bong Bong’ Marcos, son of the president of the Philippines,” Collins wrote. “Marcos has lived in Cherry Hill since he became a graduate student at the University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School of Business in 1979, although he no longer attends the school,” he continued.

The two bodyguards were identified as Carlos Paredes and John Velasco. A John Francis Velasco is included in the US Department of State’s Diplomatic List from 1984 to 1986, identified as an attaché of the Embassy of the Philippines in Washington, D.C. An article in the November 12, 1986 issue of National Midweek, written by Bonifacio Gillego, says that Velasco was actually a military intelligence officer, with AFP serial number 0-5867, listed as an attaché since 1980, and that he “commuted between Washington, D.C. and New York, with New York as his area of intelligence jurisdiction.”

Gillego added: “When Bongbong Marcos was studying at Wharton, Velasco and Charlie Paredes, another army man, provided him with security, drawing personnel from the Philippine Embassy in Washington. It seems that these enlisted men-bodyguards were amply rewarded for their canine servitude to the dictator’s son. Most of them [as of November 1986] are still in Washington, D.C. and New York.”

The Americans knew all about these intelligence-gathering “diplomats.” Among the files in the Digital National Security Archive is a document labele” [FBI Lists Philippine Intelligence Officers in the United States along with Their Diplomatic “Covers”].” It is a confidential cable from the US Federal Bureau of Investigation, dated August 17, 1981. Several persons are described therein as falling “under headings of ‘Area of Operation: PH [Philadelphia, where Wharton is] and New Jersey,’” including “Capt. Johnny Velasco” described as a “P.S.C. Officer,” and “son of former Gen. Segundo Velasco,” whose “cover is an attaché (at the A.F.A.O., Phil. Embassy in Washington).” The list does not include a Charles or Charlie Paredes, but does include a “Major Arsenio Paredes, also described as a “P.S.C. Officer” whose “cover is a civilian employee in the Consulate-Chicago.”

The FBI cable also mentions “Major Julian Antolin (National Intelligence and Security Officer, N.I.S.A. [National Intelligence and Security Authority, then headed by General Fabian Ver]” whose cover was “an attaché to the United Nations.” Antolin is listed with Bongbong In the December 1979 edition of the Permanent Missions to the United States: Officers Entitled to Diplomatic Privileges and Immunities. Another Cherry Hill house—in Capshire Drive, a short walk from the Pendleton Drive one—where Bongbong’s bodyguards stayed was purchased in Antolin’s name, before it was transferred to Irwin Ver, Fabian’s son. Both houses have since been sold.

Besides guarding Bongbong, the main mission of Velasco and Paredes, among others, was to gather information about and disrupt the anti-Marcos opposition in the United States. Gillego, a former military man himself, described how these men operated in his Midweek article: “In the language of their clandestine trade, these military personnel masquerading as diplomatic or consular officials were case or project officers. Each developed his own network of agents and informants recruited from among the members of various anti-Marcos organizations in the United States.” The penetration agents were “assigned to obtain critical information; to sow discord and promote intrigues; to sabotage operations of these organizations and compromise them with US authorities,” Gillego wrote.

Collins, in his Courier-Post article, described another suspected activity of Velasco and Paredes in this manner: “one federal investigator said it involves ‘a sort of sophisticated form of gun-running’ in which foreign nationals take advantage of legitimate loopholes in federal and state firearms laws….[the investigation] is believed to center on the purchase of an estimated 75-80 handguns over a two-year period. Federal government agents believe the Filipinos may have been black-marketing the guns in their homeland, using profits from the sales to finance frequent trips to the Philippines.”

According to Collins, Paredes and Velasco in particular were “believed to have made a series of gun purchases” in a store in Pennsylvania, about 16 kilometers from where Bongbong studied, “each time relying on a letter from the Philippine consul general’s office as the authority needed to obtain the weapons.” They preferred buying in Pennsylvania because the gun laws there were more lax than in New Jersey and New York. The deputy consul at the Philippine consul general’s office in New York explained that they were only permitted to “take up to four weapons out of the United States at one time.”

Collins further noted that from available information, “several of the guns acquired by Marcos’ men are the type specifically preferred by police, particularly undercover agents who require weapons that can be easily concealed.” Collins tried to reach Paredes, Velasco, and Bongbong for comment, but these efforts were “unsuccessful.” According to Collins, no charges were filed “because of the immunity granted by the United States to visiting foreign dignitaries” and “the long history of friendly relations between the United States and the Philippines.”

It seems likely that the story did not gain more traction, partly because of the state visit of Ferdinand Sr. to the United States in September 1982. Bongbong, along with his sister Irene, apparently also a student at the University of Pennsylvania at the time, accompanied their parents during the state visit. As reported by the Associated Press, on the last day of their US tour, Imelda headed to Philadelphia to visit the University of Pennsylvania where two of her children “attend the Wharton School of Finance.”

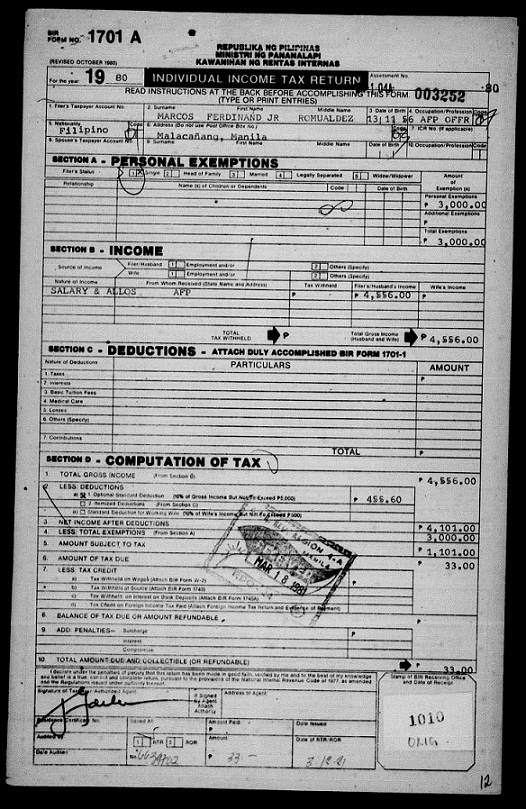

Could 2nd Lieutenant Ferdinand R. Marcos Jr. of the Presidential Security Command, AFP serial number 0-113885, have also been a “case or project officer” who engaged in gunrunning on the side? Although Bongbong infamously failed to file his income tax returns back when he was vice governor and governor of Ilocos Norte in the 1980s, among the digitized files of the PCGG is an ITR filed in 1981 for salaries and allowances that he had received as an AFP officer in 1980. He received over PHP 4,550.00—over PHP 120,000.00 today. Was he “on duty” then while ostensibly an attaché and a graduate student?

At the very least, it seems unlikely that he did not know about the activities of his fellow “attachés.” He knew about the people they were monitoring. Businessman and opposition leader Steve Psinakis, in his book Two Terrorists Meet, recounted a brief encounter with Bongbong during his infamous December 19, 1980 meeting with Imelda at the Waldorf in New York. After Psinakis had discoursed with Imelda for almost two hours, Bongbong entered the lavish suite where the meeting was taking place. Psinakis made light of rumors that Bongbong was being targeted by the anti-Marcos opposition in the US, which he denied. Psinakis later learned that, while Bongbong was still outside the suite, upon learning that Psinakis was talking to his mother, the young Marcos said, “Oh! This is the fellow who is going to kill me. I want to see him.”

Bongbong has repeatedly distanced himself from abuses and atrocities committed during his father’s time. But has he really explained what he did for his father during the dictatorship?

(Miguel Paolo P. Reyes is a university research associate at the Third World Studies Center, College of Social Sciences and Philosophy, University of the Philippines Diliman. This piece is part of the Center’s ongoing research program, the Marcos Regime Research.)