We do not have a Borobudor, or an Angkor Wat. Instead, we have colonial stone churches, hundreds of them scattered across the archipelago. Architectural influences overseas led to different styles and designs of stone churches in the country synthesized locally to suit the prevailing taste of the times. Thus, we have a distinctive church architecture, uniquely Filipino.

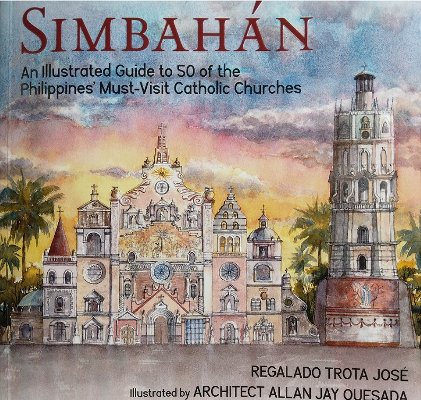

Simbahán: An Illustrated Guide to 50 of the Philippines’ Must-Visit Catholic Churches (RPD Publications, 2020) by Regalado Trota José introduces 50 churches that have been selected for their architectural significance, well-preserved ornateness, or picturesque settings. Illustrated by Architect Allan Jay Quesada, it is divided into ten geographic sections, from Batan Island, Batanes to Mati, Davao Oriental.

Reading it leads to a fresh appreciation on the role of churches in Philippine life.

The arrival of the Augustinians started the formal building of churches in 1565. Four of the Baroque churches on the UNESCO List of World Heritage Sites are included, namely San Agustin in Intramuros, Manila which is the oldest stone church in the Philippines (1586-1604); Paoay, Ilocos Norte; Santa Maria, Ilocos Sur, and Miag-ao, Iloilo.

Local materials

As a tropical archipelago, the early churches were built with bamboo, nipa thatch, and hardwood, all easily destroyed by fire, typhoons, and termites. Later, sturdier materials were used such as adobe, bricks, coral stone, limestone, rubble, river stone, or basalt rock based on its local availability. Adobe in the country refers to natural stone cut from volcanic tuff quarries; in Latin America, it refers to dried blocks of clay and straw. Stones and bricks were cemented together with mortar, a mixture of lime and water strengthened with puso-puso plant or mango leaves, molasses, or egg whites. (The abundance of egg yolks led to the making of traditional biscuits and desserts, which is another story.)

In northern Luzon, brick was an essential building material; in the Visayas, coral stone churches abound.

Learning lessons from previous earthquakes, church reconstruction led to the style of “earthquake Baroque” – squatter and wider than taller, and with thicker walls. Its most outstanding example is the Paoay Church in Ilocos Norte with its row of massive buttresses that reinforce walls against earthquakes.

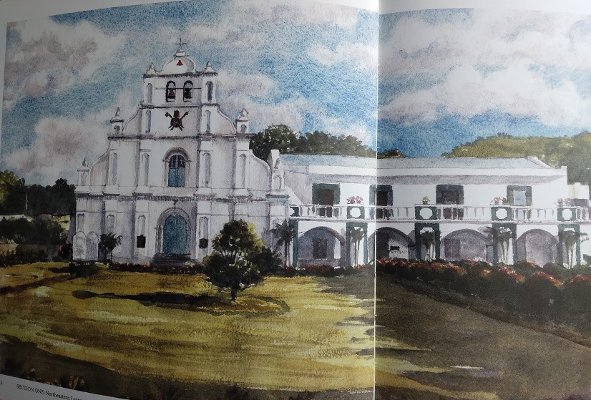

The church complex has become a familiar layout for Filipinos; it includes the church itself, a bell tower, and a convento or rectory. A school and houses of prominent families complete this typical layout. Fronting the church is a spacious plaza, a truly public space for everyone.

Inside Simbahán

Four succinct paragraphs describe each church with a historical and geographical background, sociopolitical events relevant to the site, the year of construction, the religious order in charge, and its unique characteristics. It also describes the retablo, an elaborate centerpiece of the altar in front of which mass is celebrated.

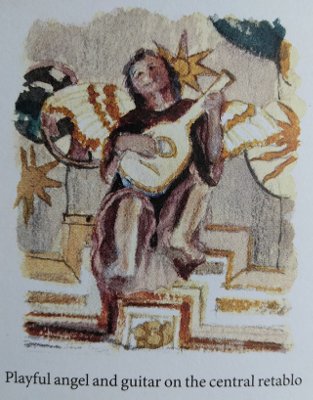

Three illustrations are done for each church: a main façade of the whole church, a closer look at its retablo, and a detail of a unique feature, such as an angel blowing on a carabao horn, a fish-tailed rooster weathervane, or finely-cut coral stones in the cupola of a bell tower.

Much better than photographs, Quesada’s watercolor illustrations capture vividly the detail, color, and proportion of the churches – the patina of its historicity.

Sweat and toil

Priests, military engineers, and foremen, Chinese and local, designed the churches. The community provided labor of all kinds: in exchange of tribute, voluntary, paid, or forced labor known as polo y servicios under Spanish colonial rule. It also provided food and other materials.

Nameless Filipinos gave their sweat and labor to build these churches; anonymous craftsmen, local, Chinese and Muslim master builders, and Japanese carpenters, left their own artistic imprints. For one, Chinese stone lions are found in a number of churches.

Historical markers today need to acknowledge the role of these anonymous builders and artisans.

Scholar and writer

Researching and writing on the cultural heritage of Hispanic Philippines since the 1980s has been Ricky Jose’s life passion.

With an A.B. in anthropology and an M.A. in Philippine Studies from the University of the Philippine, José’s graduate thesis on Spanish colonial art was published as Simbahan: Church Art in Colonial Philippines, 1565-1898 in 1991. It won a National Book Award in art in 1992. Currently, he is the archivist of the University of Santo Tomas and teaches at its Cultural Heritage Studies Program.

In celebration of the 500th year of the arrival of Christianity in the country, José advocates for a better way of conserving our church heritage, by having a judicious conservation management plan, not only for the church itself but also its entire complex. (see YouTube, 08 March 2021)

The illustrator

Allan Jay Quesada, with an architect’s expertise and a delicate hand, is behind all the superb illustrations of the book. An architecture graduate of the Pamantasan ng Lungsod ng Maynila, he started watercolor painting at the age of five.

He is a member of the Watercolor Society of the Philippines and the United Architects of the Philippines, Manila Maharlika Chapter.