Filipino scholars proposed a community engagement plan as the most suitable strategy to thwart disinformation that has taken on creative forms and given rise to influence operations in the country.

The recommendation, part of the report titled “Parallel Public Spheres: Influence Operations In The 2022 Philippine Elections,” is the result of a study which unmasked newer evasive forms of influence operations in the country and put emphasis on the importance of a “critical perspective” in local disinformation and digital literacy studies.

“This means alerting citizens not only about artful disinformation narratives and recruitment strategies in our homegrown disinformation economies; it also means empowering citizens to apply their passion and creativity toward strategic collaborative interventions rather than those that deepen social divisions,” it added.

Part of the plan is to change the narrative around disinformation, ease access to resources related to disinformation and digital ethics, and support whistleblowers to expose disinformation-for-hire industries.

During the academic launch of the study at the Malkin Hall, Harvard Kennedy School on Friday, one of its authors, Harvard Kennedy School Shorenstein Center Fellow Jonathan Ong, said the report tells an underlying story about the failures of listening and the need for more collaboration as the nation moves forward.

Aside from Ong, the other authors are Jose Mari Lanuza of the University of Massachusetts Amherst, Rossine Fallorina, Ferdinand Sanchez II, and Nicole Curato.

The authors/researchers underscored the need to open discussions and address issues related to local disinformation-for-hire industries. They suggested developing mechanisms that will ensure the safety and protection of “whistleblowers” who may come forward to expose their organizations’ complicity with disinformation operations.

The researchers also highlighted the need for strategic policy advocacy and participation in “south-to-south learning spaces.”

Talking on behalf of his team, Ong argued that while there is a strategic need to align with international policies, Filipinos should not be dependent on frameworks from the global north alone.

“We need to offer sociological solutions that empower communities to address social problems at their roots,” he said.

The team aims to connect with collaborators from diverse sectors and provide funds to support organizations and individuals who can effectively advance their community engagement plan.

“We think it’s a hopeful plan. It recognizes that ordinary people are active agents capable of political deliberation. It rejects the disempowering premise that social media are totalizing forces that have brainwashed the so-called uneducated masses,” Ong said.

He explained that this report is a manifestation of what Joan Donavan, research director of Shorenstein Center, calls a “whole-of-society approach” to address disinformation. It shows what the concept looks like when it is put into practice amid growing frustrations and social divides among the masses.

“The kinds of solutions we can offer are really dependent on how we understand the problem, to begin with. So, if we only have a superficial or abstract grasp of the problem or issue, that will lend itself to band-aid solutions” Ong said.

“For us to put up a good fight, we argue we really need to understand in depth what the enemy is and where they’re coming from,” he added.

Unmasking newer evasive forms of influence operations

During his presentation, Ong shared that their study focuses on “the cumulative impact of latent disinformation and historical distortion over the past year and newer evasive forms of influence operations which have now resulted in what we call parallel public spheres.”

Parallel public spheres, according to him, arose from society’s failure to agree on shared facts and people’s unwillingness to engage in civic debate.

In their study, the researchers noted that tactics used in the 2022 elections went beyond what can usually be considered “disinformation”, thus evading fact-checking efforts.

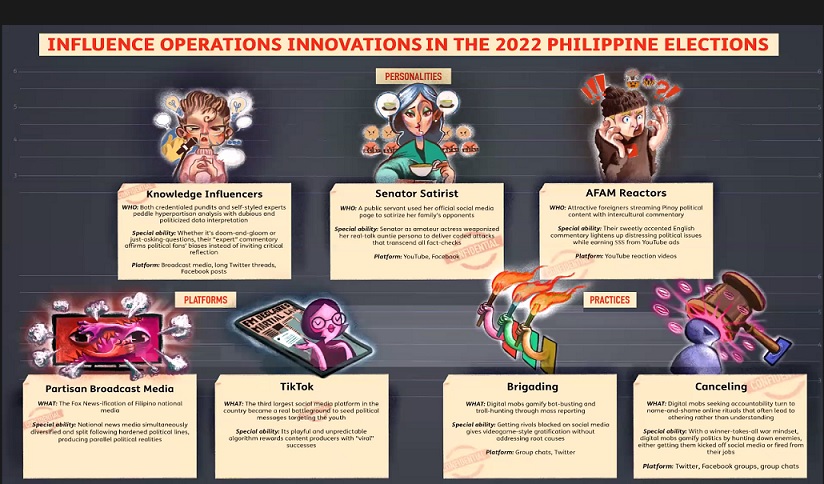

This called for the use of the broader term “influence operations” which refers to “strategic communications that aim to hack attention, mobilize audiences, and influence electoral outcomes”.

Ong said these influence operations are neither illegal nor deceitful but are exploitative of many gray areas of campaign finance regulation, platform policies, and journalistic norms. Further, they toy with the real feelings and grievances of citizens.

Moreover, the study found that influence operations “build on cumulative impacts of longitudinal disinformation,” exemplifying the years-long efforts of rebranding the legacy of the Marcos family through historical distortions.

“If previous versions of historical distortion were expressed as crude memes or crude YouTube videos, or artificially trending hashtags, now we’re seeing new expressions come in the form of fictional entertainment, blockbuster movies, influencer collaborations, and career fanfictions,” Lanuza said.

He added that these tactics are all being justified by what they call “knowledge influencers”. Lanuza mentioned that based on their research, historical distortion is no longer simply a matter of “falsehoods” but analyzing the strategic performance of “false victimhood.”

“It sounds like if our family has long been the victim of liberal elite politicians, historians and journalists who have long suppressed the real truth of Martial Law… If our family, as powerful as it is, falls victim to that, what more you? That’s what it’s looking like,” Lanuza explained.

Aside from knowledge influencers, other personalities they observed include “AFAM reactors” or attractive foreigners streaming Pinoy political content and “Senator Satirist”, referring to Sen. Imee Marcos, who used her social media to satirize her family’s opponents.

The researchers also found that practices of brigading and canceling had been rampant in recent elections.

Brigading, according to the report, is a bot-busting and troll-hunting effort done through “mass reporting”. Cancelling, on the other hand, refers to accountability-seeking turned name-and-shame online ritual that often leads to othering rather than understanding.

“Brigading and canceling, we see, observed a critical role in the Philippine public sphere. They protect whatever spaces are left to defend historical truth and assert the presence of a political opposition, committed to holding the Marcoses and their allies accountable,” Lanuza said.

However, they noted that these practices have also backfired because for Marcos supporters, these tactics only reinforce the idea that the so-called truth defenders and activists are the “bullies”.

“Fighting fire with fire, it sounds sexy. It may be the only tactic that some critics of the Marcos family have left. But if there’s anything that can be learned from the decades of Marcos restoration, this is about changing people’s minds. It’s a slow burn,” Lanuza said.