My entry point to Nora Aunor’s icon was borne of the women around me as a child. First my mother, who is a Noranian—the kind that watched her critically-acclaimed films, was happy to hear Nora expanding her repertoire with Richard Merck, even if in 1980 she got the chance to do an interview with the Superstar, and was made to wait for so long and was limited to so few questions, confirming—and writing about—the urban legend that was the Superstar’s diva behavior.

The other woman was my first yaya. I have few memories of her, save for two: she was a lesbian, and she was a Noranian. Mama would buy her all the fan magazines with Nora on the cover, she would watch Nora’s movies on her days-off, and she treated Superstar on RPN 9 like weekly mass she needed to attend. For a stretch, she would constantly re-read these tiny pocketbooks that were Nora’s biographies.

Yet, I was no second-generation Noranian. As I told an audience of Noranians during a forum to discuss President Noynoy Aquino’s refusal to confer her the National Artist Award in 2014, I am of a generation that grew up choosing between the taray of Maricel Soriano and the pa-tweetums of Sharon Cuneta. The taray queen (of course) was my icon.

Now I realize that much of who Maricel (and later on Judy Ann Santos) could be as a popular icon was borne of Nora. The non-conforming, non-people-pleasing, real and truthful, complicated and complex woman, of a different shape, size, and tenor, with diverse inclinations—this was a path paved by Nora.

Growing up with Nora politics

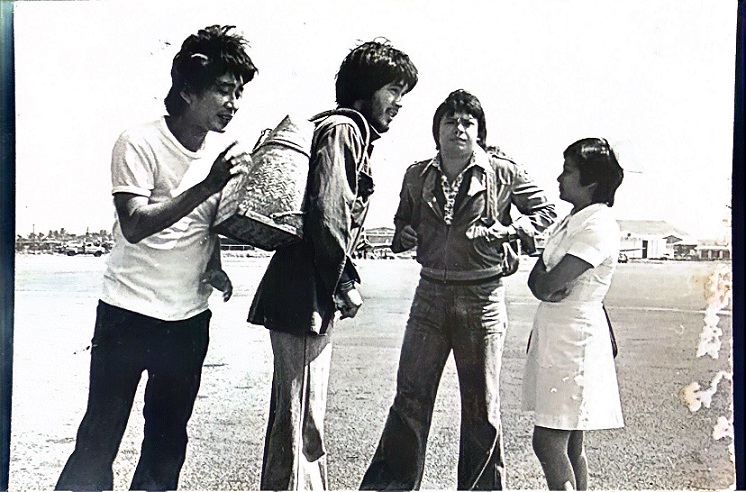

Born in the mid-70s, I grew up knowing Nora Aunor as Superstar. My awareness of her was about the weekly TV show, where she sang, danced, and bantered with Kuya Germs and Jograd dela Torre. This version of her seemed more real, like she was free to be herself here, speaking in her signature quiet Tagalog, humble if not self-deprecating, enjoying the diverse songs she was being made to sing, throwing punchlines with the best of them when needed.

As I grew into socio-political awareness, Nora was a constant. She was Marcos loyalist who in 1986 appeared at the gates of Camp Aguinaldo for the EDSA Revolution, taking part in people power when it was time to kick Marcos out. We know of her loyalty to Erap, sure, as she would have it for FPJ—these are invisible showbiz ties that bind. Yet we also saw Nora cut those ties in 2001at EDSA Dos, when she came and stood with us as we kicked Erap out of office.

Popular politics has always had Nora, which is to say that my sensing of her as Superstar was as much about local pop culture as it was about the socio-political. Nora was one to appear at protests specific to issues, from higher wages for teachers to justice for victims of State violence, as she would endorse a diverse set of political aspirants every election (and even hope to win an election or two herself). This public persona is one that is heavily criticized, judged as being balimbing, with all its inconsistent political convictions.

Yet Nora might have been on to something.

The issues of nation are diverse, our engagement with these, complicated. Nora’s politics was emblematic of this complexity—trying to keep track of issues, swinging across the political spectrum, blind to political lines, taking stock relative to the urgencies. It cannot be consistent precisely because of its responsiveness to a specific present, it is not consistent because there is always space to learn more and differently, it is not consistent because we have the freedom to rethink and revise, engage and disengage. Be, as much as become.

Nora’s political engagement is less problematic as it is emblematic. It is emblematic of the Filipino’s ways of engaging with the country’s governance and dominant politics, removed as this is from the people’s struggles, speaking as it does in another language, ensuring as it does that justice and fairness are always beyond reach. Nora was one of us, simply engaging in the ways she knows how, ways that hopefully matter, sometimes making mistakes, making wrong choices, sometimes getting it right.

Nora’s politics was always in flux. There is a lesson to be learned from that.

La Aunor of film

It would be difficult to go through the humanities at the State University without Nora being part of required films and readings. We read every piece of important scholarship on Nora, and watched her more iconic films: Tatlong Taong Walang Diyos, Bona, Minsa’y Isang Gamu-Gamo, Bona, Himala.

But it would be the films that I saw by choice, about which I would write reviews, that formed my sensing of Nora as artist: Bakit May Kahapon Pa? (1996), Babae (1997), Sidhi (1999), Naglalayag (2004), Thy Womb (2012), Ang Kwento ni Mabuti (2013), Kabisera (2016), Hinulid (2016).

This experience of Nora through her later films is one of my generation’s. It is of those who might not be Noranian but whose education about nation continues through the consumption of film, the consumption of Nora. I remember watching Sidhi twice, once in U.P., the other time in a cinema with Mama, and both times with the audience cheering Ana as Nora brought her slowly to becoming the embodiment of rage, one nurtured by an uncanny sisterhood.

I remember seeing Naglalayag and being surprised by how this characterization of a lonely, widowed, middle-aged female judge could so believably fall into a relationship with a taxi driver half her age. While we give Yul Servo’s portrayal of Noah some credit, we all know that Nora’s Judge Dorinda—her banter, her lightness, her class specificity—is the reason this premise worked at all.

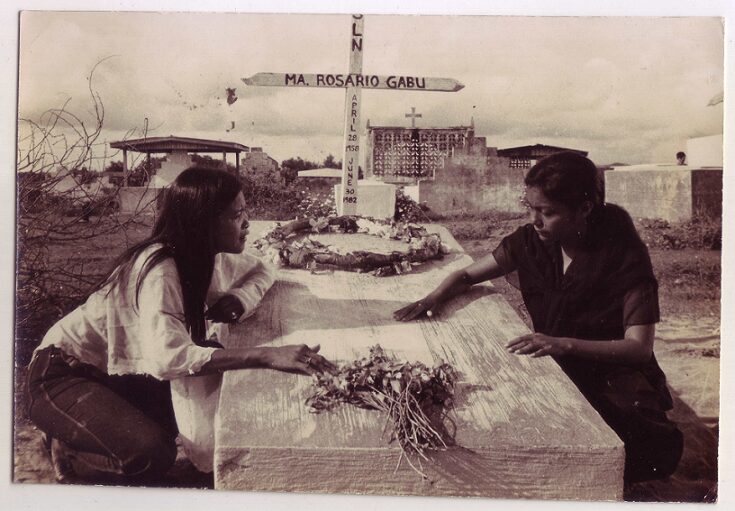

When I think of Nora, I think of Kabisera, a film off the Metro Manila Film Festival of 2016, less than a year into Duterte’s drug war. At that point, the unofficial number of dead in this war against the poor was close to 7,000, and we are introduced by Nora to Mercy, a mother of five, wife to a barangay captain who is murdered. Mercy navigates the realization that her husband is no saint as she grapples with the evil of extrajudicial killings and a justice system skewed in favor of the powerful, while showing us a woman beyond stereotypes—both ilaw ng tahanan, but also haligi, its light and its foundation, its voice of reason, its sense of humanity. What I remember is this transformation of a woman as wrought by the political violence on her personal life, and through Nora’s Mercy, it was easy to see that this was all of us grappling with a presidency that would continue to kill for six years.

And then there was Ang Kwento Ni Mabuti, a wonderfully simple, honest story about poverty that unfolds through Nora’s portrayal of the lead character Mabuti. Grandmother to four children, her days are filled with caring for their small plot of land, making sure that mouths are fed, and those in need of healing receive care she can offer. Mabuti is the hilot in a community that cannot even imagine any other kind of healthcare. Mabuti walks, speaks quietly, engages deliberately with community, even as she leaves it for the city to deal with the bureaucracy. Instead of the city changing her, Nora shows Mabuti to be on a consistent even keel that seemed less resignation and more the beginning of a form of indignation, one that sears though the calm, quiet, downtrodden demeanor. By the time Mabuti’s character is tested, it is the magic of Nora’s portrayal that makes us root for her, regardless of right and wrong, because we want her to do what’s right for her, given her circumstances, given this twist of fate. Nora made Mabuti this character.

And in many ways, Mabuti is Nora.In defiance of all our expectations, making us question our own sensing of right, wrong, and everything in between. The best of her characters are neither black nor white but a combination of both, and this is as much about the way Nora attacks these characters and introduces them to us, as it is about how she, as Nora Aunor, becomes these characters’ embodiments—complex yet profoundly simple, complicated but also just basically human.

La Aunor was an honorific I always loved for Nora, because it is one that speaks specifically of her artistic prowess that is really, in her hands, a power—this ability to deliver profound characters, no matter how seemingly stereotypical, no matter how simple. With Nora, no character ever was.

Nora and the Noranians

My first real engagement with Nora happened through her Noranians.

In 2011, Nora was cover girl of Yes! Magazine, coming back after years away, during which all the news carried about her were stuff of controversy: she had married a lesbian friend, she was facing drug charges, she lost her voice in a botched Japan operation. It was a pretty good tell-all interview, but few got beyond the cover photograph of Nora: a Mark Nicdao black and white photo of her wearing a stylized low neck collared shirt, standing tall, one arm across her waist, cradling the other arm with the hand that holds a cigarette. She stares straight at you, unapologetic as she is inexplicable. Superstar, regardless of what we’ve heard. Superstar, still.

Anti-smoking advocates, medical associations, civil society sounded the call against Nora, calling her a bad example for promoting smoking. It was a non-starter of an issue, something Nora brushed off, but which we now know set the stage for the controversy that would matter.

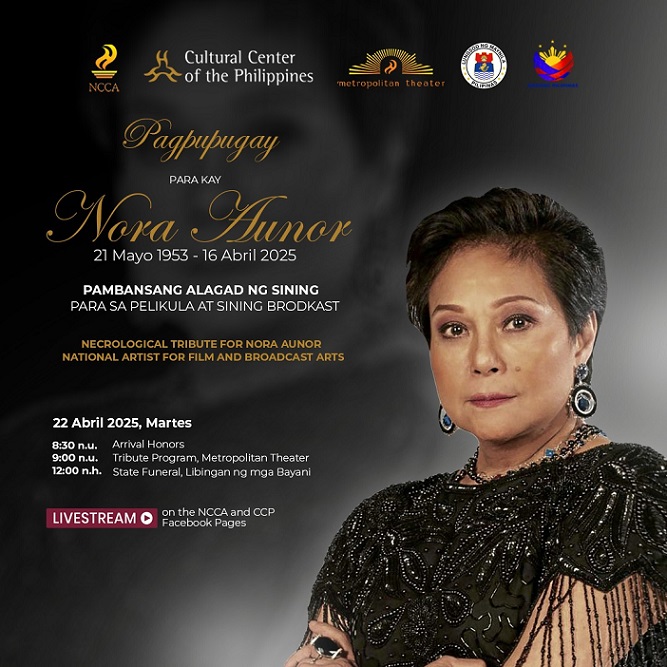

In 2014, while Nora was part of the list of artists recommended for the National Artist Award by the National Artist Award Committee, then President Noynoy Aquino refused to confer her the award. It was clear that this decision was not at all about Nora as artist, but about the bias of a Catholic, conservative, Liberal president, who was judging Nora for the life she lived. The President himself admitted that his refusal to confer this award to Nora was about how it would make her “someone to emulate” and as such he couldn’t give it to her as someone “convicted for drugs.” The latter was a lie—one that even Nora’s U.S. lawyer denounced.

PNoy was of a Catholic patriarchy, and it was no surprise that he would think little of a woman like Nora—her life and her character, her persona and her celebrity. Nora was a representation of a humanity that was too real, too different, for comfort; she was simply unacceptable.

That this was unjust will never be water under the bridge, especially because in 2018 President Rodrigo Duterte would again remove Nora from the list of National Artist Awardees, with his press secretary saying that this was to “spare” Nora from another controversy. It was classic double-speak from a populist leadership that silenced many artists through a climate of fear and normalized redtagging as a weapon against critics—artists, included.

In 2022, when the Duterte government decided to confer the NAA to Nora, and she was conspicuously absent from the ceremony (for whatever reason), it just felt like justice.

Writing about Nora at these moments, speaking of her value beyond the limits set by the dominantly male, conservative, powers-that-be, highlighting the importance of her iconography to a mainstream that cannot even begin to appreciate her, speaking to her uniqueness and specificity, her stardom and celebrity, her political and personal life, her being Ate Guy—this means speaking to her Noranians.

And they are a force to be reckoned with. This is a fandom that is not simply about blind idolatry, as it is about an insightful, if historical, understanding of Nora. This is an appreciation of her as bound to her impoverished back story, her rise to stardom, and her continued struggles with the systems that sought to dismiss her, put her behavior into question, and ultimately discredit her. This is a fandom that cuts across social classes and conditions, from the academe to the masses; it is inherited from one generation to the next, shared across friends, communities, political loyalties.

Ate Guy of nation

The death of Ate Guy has filled our social media feeds with exactly the history that her Noranians live off, and it is one that too many of us failed to appreciate while she was alive, more focused as we were on the controversies and issues. If we cared to look at the right things, we would know that Ate Guy, across her body of work and artistry, her personal and political lives, her private and public selves, was national artist long before she was declared such, her influence beyond measure, the breadth and scope of her reach unlike any other. Many scholars, Noranian and otherwise, have studied this power of Ate Guy’s persona, and how no one will be able to match it. She is National Artist with a claim to both “national” and “artist” like no other National Artist can lay claim to.

But Ate Guy is a gift that keeps on giving. Watching her interviews now, I have become fascinated by the bits and pieces about her decision to produce films, something she kicked off early in her career. It speaks less to a capitalist inclination, and more to an intellectual acuity that few ascribe to Ate Guy, but which is in her decision to make films she knew might not be made otherwise. This contextualizes for me a film like Tisoy! (1977), written by Nonoy Marcelo, directed by Ishmael Bernal, produced by NV Productions—a film made up of skits and fragments of the absurdity of Martial Law Manila, a daring project right smack in the middle of the violent regime.

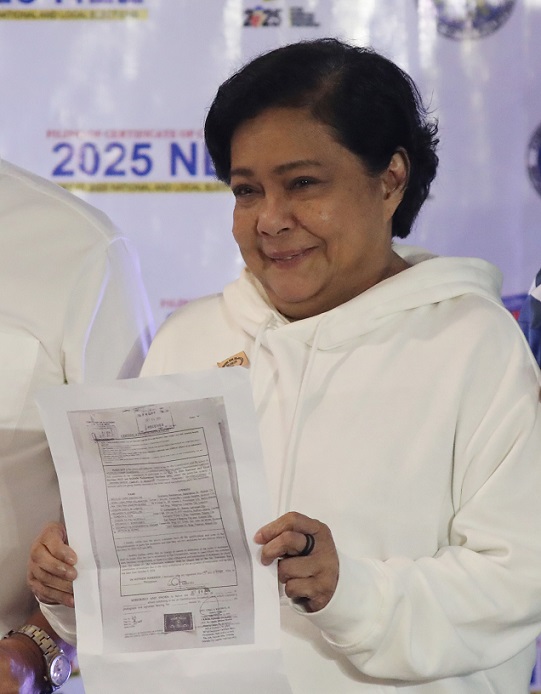

I feel lucky to have engaged with Ate Guy’s icon later in her career, because as she grew older, she also became more comfortable in her own skin, speaking as she might, doing as she wished. Instead of mellowing as she aged, she became even less compliant. Her public-private persona continued to be a defiance against the fakery, the polished images, the conservative articulations of celebrity, the violence of politics, the state of the nation.

That there are still lessons to be learned through the superstardom of Nora Aunor, the prowess of La Aunor, and the truths of Ate Guy, is a testament to her complexity, as it is to her rarity. She was rebel without trying, and now I think it is something she constantly nurtured, something that she built into her creation of this public self, grounded in her personal history of struggle, in negotiation with the fame and money she worked hard for, engaged with the nation that cradled her becoming, against the powers and systems that constantly sought to take her down.

We are lucky to have had her in our midst, to have her in our socio-cultural-political history, to have known her icon.

In life and in death, Nora Aunor is without rival. Long live, Ate Guy.