For his last hurrah in office, Rodrigo Duterte had the privilege of spending a total of P4.5 billion in confidential and intelligence funds. How he spent that colossal amount will never be known.

As has been extended to the present president and vice president, Duterte was shown courtesy by Congress, meaning it never questioned how one national government agency has at its disposal P12,328,767 per day to spend. Think of what that amount can do for a poor country. Courtesy is a crap of a euphemism. Congress is the first line of defense for the public interest of protecting taxpayers’ money. Instead, it gives the imprimatur for non-transparency and for the possible misuse of such funds.

Compare Rodrigo Duterte’s with the modest confidential funds of previous presidents: Gloria Macapagal Arroyo had P600 million; Benigno Aquino III had only P500 million. The Commission on Audit says confidential funds for the Office of the Vice President under previous administrations were miniscule or even non-existent.

What exactly does the COA say about what the funds are NOT for? The 2015 Joint Circular of the COA and the Department of Budget and Management prohibits the following: salaries, wages, overtime, additional compensation, allowance or other fringe benefits of officials and employees who are employed by the government in whatever capacity or elected officials, except when authorized by law. Also prohibited are representation, consultancy fees or entertainment expenses, and the construction or acquisition of buildings or housing structures.

The confidential fund is a lump sum fund. It is given whole, not by tranches. No line items are required as to how it will be spent. All that the COA requires is a physical and financial plan supporting the request, containing the estimated amount per project, the activities and programs. Given this simplistic formula for an amount that is enormous, its final report on how it was spent can easily be fictionalized. Lying is standard operating procedure in Philippine governance.

It goes without saying that the devil is in the details. COA cannot audit the final report because no liquidation is required. It merely accepts a general report of how the money was used. It cannot release that report to the public because of its “confidential” nature. In short, there is no oversight. It is a self-defeating window that COA and the DBM should not have allowed in the first place. COA, for one, does not have naiveté about the state of corruption among public officials.

The opinion journalist and academic Segundo Romero references Robert Klitgaard who famously defined corruption as monopoly plus discretion minus accountability (C=M+D-A). “Confidential and intelligence funds fit these conditions to a T.”

Romero articulates the first level of the slippery slope to confidential corruption as “ballpark estimates in the billions for fuzzy tasks that could not be verbalized commensurate to the gargantuan amounts bandied about.”

As to its ludicrous reporting system, Romero counters: “The results will be invisible, intangible, mythical, or occult, as befits the purported clandestine nature of the funded activities. The sheer amount of the funds will involve a huge network of individuals, the larger the more difficult to exact accountability.”

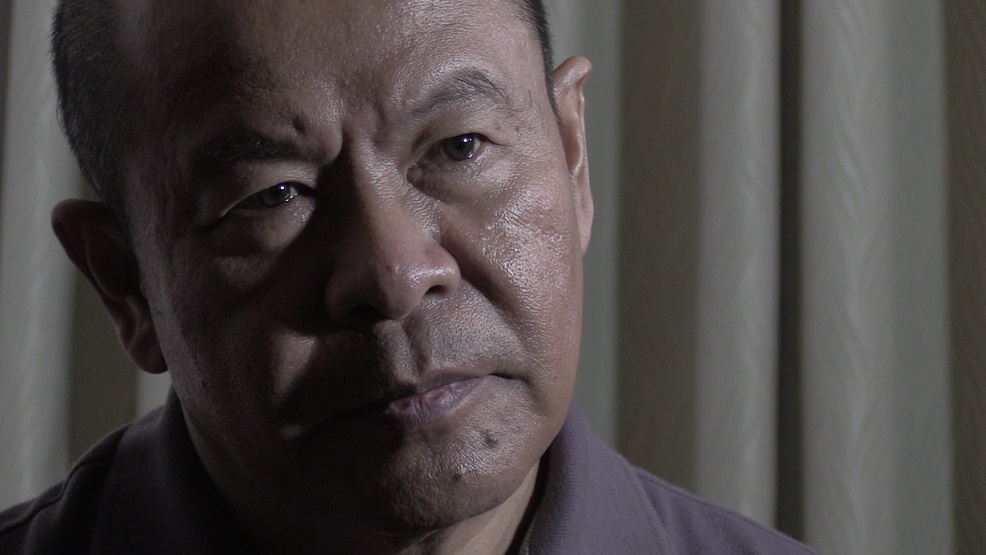

Consider how Rodrigo Duterte spent clandestine money that could have come from his confidential and intelligence funds when he was city mayor. His trusted police hit man Arturo Lascañas confessed being a ghost employee of the Davao City government as member of the Davao Death Squad. In an interview with VERA Files he said he received P68,000 every month from the Davao City government. The amount was pooled from 10 to 12 ghost employees whose salaries ranged from P5,000 to P7,000 a month.

Whatever the source for this illegal reward system, Duterte was the wrong man to have been privileged with unaudited confidential and intelligence funds when he became president. His other former hit man Edgar Matobato would narrate in the interview he had submitted to the International Criminal Court:

“We were ghost employees, the so-called ‘15-30’ of city hall. Sometimes the mayor would treat us to food after a killing. He also provided guns to barangay captains.” Notice the elements prohibited by the COA in this narrative: salaries, wages, additional compensation, allowance, representation, and entertainment.

The recent pronouncement of budget experts hit the nail on the head: “Massive amounts of confidential funding should not be the norm in government, as it does not have the same transparency mechanisms as ordinary budget items. More importantly, given our limited fiscal space, every peso of funding for specific public services counts, and confidential funds tucked in specific offices do not serve this end.”