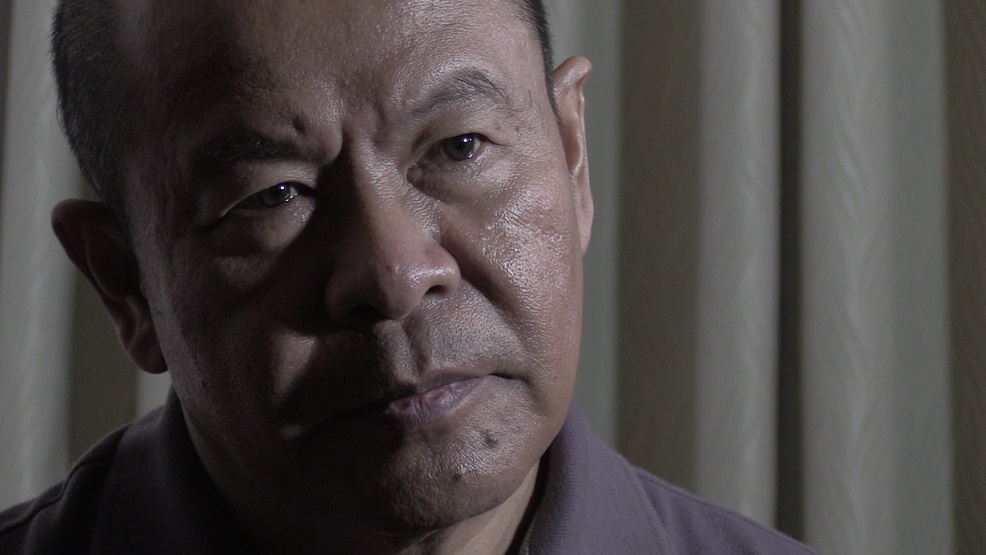

In the business of death, self-confessed hitman Arturo Lascañas had reaped a ghastly reward: He became a “ghost” employee of the Davao City Hall, whose paycheck got a boost from the salaries of other “ghost” employees.

Lascañas, who retired in December with the rank of senior police officer 3, said in an interview with VERA Files that he received P68,000 every month from the Davao City government as a member of the Davao Death Squad (DDS).The amount, he said, was pooled from 10 to 12 ghost employees whose salaries ranged from P5,000 to P7,000 a month.

Lascañas is the second person to admit having collected money from the Davao City Hall as a ghost employee, in return for being part of the DDS that he said carried out summary executions of suspected drug dealers and other individuals on Duterte’s orders.

Edgar Matobato, a former member of the Citizen Armed Forces Geographical Unit in Davao, testified before the Senate Committee on Justice and Human Rights on Sept. 15 that he was on the city’s payroll as a member of the Civil Security Unit but only worked to kill individuals who he was told were “criminals.”

The Commission on Audit , in its 2015 report, questioned Duterte and other city officials for spending close to P708 million the previous year on more than 11,000 contractual workers. The COA, though, stopped short of calling them ghost employees.

The audit report formed the basis for the plunder case Sen. Antonio Trillanes IV filed against Duterte on May 5, 2016, four days before the presidential election.

The hiring of ghost employees is also one of the charges in the impeachment complaint filed against the President by Magdalo Partylist Rep. Gary Alejano on March 16.

Lascañas pointed to now retired SPO4 Sanson “Sonny” Buenaventura, bodyguard and driver of Duterte, as the one who,he said, arranged his inclusion in the Davao City government’s payroll through ghost employees.

Lascañas said, “Binigyan ako ni Mayor through Sonny Buenaventura ng kumbaga quota. Siguro mga 10 tao yung quota ko, labindalawa na monthly na tig-5000 meron din tag-7,000 (The mayor assigned me a quota through Sonny Buenaventura. Maybe about 10 people or 12 with a monthly pay of P5,000. There were also those with paid P7,000).”

The retired police officer said only two or three names on the list were real people. “The rest is imbento na lang namin na pangalan (We invented the names of the rest),” he said.

Lascañas said the “quota” referred to the number of ghost employees from whose salaries he would derive his own monthly fee to cover his expenses.

“Parang force multiplier ko yun… Kumbaga may salary sila monthly, pero ako ang kumukuha (The quota is something like my force multiplier. Their salary is supposedly monthly, but I was the one collecting). In short, ghost employee,” he said.

As member of the DDS, Lascañas said, he also received P50,000 every month from Duterte through Buenaventura, bringing his collection to P118,000. This was over and above his P38,000 monthly salary as an SPO3, he said.

He said he gave P18,000 of his last collection in January to Jim Tan,” also a police officer and DDS member, to be shared with the other players as the squad was running short of cash.

“Kasi siya kasi may handle ng mga players namin. Sabi niya, short siya. So binigay ko sa kanya yung 18,000 so sa akin malinis yung 100,000 (Jim is the one who handles our players. He said he was running short. So I gave him the P18,000. Mine was a clean P100,000).

He said Buenaventura personally delivered to him his last collection on Jan. 4 or 5.

For the money he was given, Lascañas said, he would sign three receipts that were on yellow paper. All the receipts were under his name, but only one bore an amount, P50,000.

He said Buenaventura has all the “receipts” he signed.

Verafiles tried but failed to contact Buenaventura and Tan.

The COA had discovered that the salaries of some contractual or job-order employees in Davao City were being received by persons “other than those authorized payees” because the signatures in the receipts were different from those in the payroll.

In the more than two decades that Duterte was mayor of what is considered the world’s largest city, Davao City has had a sizable share of contractual and non-regular workers.

Between 2008 and 2015, the number of these workers—who also include job order, casual, temporary and coterminous ones—had fluctuated between 6,380 and 11,246. By December 2015, half a year before Duterte bowed out as mayor, contractual workers in Davao City outnumbered regular workers four to one.

The large workforce has time and again caught COA’s attention.

In 2014, state auditors questioned the hiring of more than 11,000 employees under contract of services and job orders in Davao City for more than P707 million, noting the absence of clearcut hiring policies, doubtful daily time records of most job orders assigned in the barangays, and contracts being entered into without the specific functions and duties assigned to employees.

“Thus, the regularity and propriety of expenditures totaling P707,726,548.01 could not be ascertained,” the COA said.

Aside from instances where salaries of contractual employees were collected by persons other than the authorized payees, the audit report also pointed out the city government’s failure to obtain the approval of the Sanggunian to charge payments for contract of services against lumpsum appropriations.

Of the 11,000-plus contractual and job-order workers in City Hall in 2014, 4,754 were with Duterte’s office.

Of the P707 million spent on these workers, P376 million or more than half was budgeted for programs directly under the mayor’s office, especially for the city’s Peace and Order Program. These appropriations were classified as “executive services (mayor).”

Years earlier, COA had flagged Davao City on the hiring and management of its personnel.

In 2007, it urged the city to fix its payroll system “to protect the city from public scrutiny and issues like ‘maintenance of ghost employees.’”

COA back then noted the city’s failure to consolidate personnel files in one central department and recommended that it develop and maintain a Human Resource Management Information System that would contain modules such as Plantilla Management Information, Non-Plantilla Management Information and Personnel Selection. Non-Plantilla refers to contractual, job-order and other workers with no regular items.

In 2012, when Sara Duterte was mayor of Davao City, the audit commission observed that the city government spent at least P677.7 million to pay 11,000 contractual workers without requiring them to submit accomplishment reports as proof of services they had rendered.

COA also said the city government might have unnecessarily spent P11.1 million on 110 consultants whose services were redundant or unnecessary because they duplicated those expected from and rendered by regular employees and officials.

When 2015 came to a close, the Davao City government had partially implemented or had yet to implement COA’s recommendations to address the problems with contractuals.

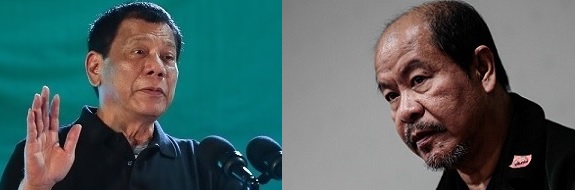

When the COA report was first released in 2015, Duterte blamed former Davao City Mayor Benjamin De Guzman for the problem. De Guzman served for only three years, from 1998 to 2001.

In his complaint before the Ombudsman, Trillanes pointed out, however, that Duterte’s immediate predecessor was his own daughter Sara, who served from 2010 to 2013. Duterte was the city mayor from 2001 to 2010.

Lascañas, who recanted his earlier testimony denying the existence of the DDS, admitted in an affidavit and in a March 6 Senate hearing that he was a “major player” in the vigilante group. He said members got their orders to kill from then Davao City Mayor Duterte.

It took two weeks for Duterte to react to Lascañas’ allegations. He dismissed them as “all lies.”—with Yvonne T. Chua. Video and photo by Daniel Abunales and Lucille Sodipe.