Photo from Uber website

Everybody wants a piece of Uber. OFWs come home to buy cars to become Uber car operators. Employees give up their day jobs, or moonlight, to become Uber drivers. Customers give up driving their fancy cars and routinely take Uber. Taxi drivers shift to Uber. Even the government joins in. LTFRB takes the biggest single bite — P190 million in just one fine. Uber has become a craze, it is the new “lechon manok” inclusive enterprise.

The TNVS model of which Uber and Grab are leading examples is largely seen by Metro Manilans who have long been suffering horrendous traffic conditions to be the single best solution to their daily mobility problems. They have cellphones, they have credit cards, and just by subscribing to the Uber service, they have prompt, efficient, and convenient car service. This option beats hands down driving your own car through the traffic and experiencing the frustrating search for parking space. It beats taking a taxi, bargaining and being exasperated by refusal before one really gets into a cab, and getting badgered for a higher fare every minute on the way.

LTFRB largely sees Uber as a flouter of its rules and regulations, and a deviant challenger of its authority. It sees danger in Uber’s ability to get and manipulate popular support against LTFRB with the help of social media and techniques of product promotion. LTFRB sees Uber as an exploitative business enterprise, out to dupe both the public, drivers, vehicle owners, and the government by presenting itself as an entity exempt from existing regulations meant for traditional transport carriers. It takes advantage of its character as a fusion of telecommunications and transportation systems to escape traditional rules applicable to each of these systems. LTFRB sees the people and drivers as being mesmerized by the immediate pay-offs of Uber service, but suspending awareness of the dangers inherent in the Uber business model and practice.

Uber sees tremendous potential to respond to the traffic woes of Metro Manilans, and earn a lot of money. No significant solution to the traffic problems of Metro Manila is as easily and instantly deployable as a TNVS (Transportation Network Vehicle System). Uber does not have to hire drivers, it does not have to buy cars, and as a result, considers itself exempt from the traditional regulations that are imposed on transport service providers.

Uber and Metro Manilans see the LTFRB as a relic from the past, unresponsive to public needs, ineffective in planning and managing public utility providers, and unable to see beyond the narrow focus on public and business compliance with their petty policies. LTFRB gets a gift of innovative service in the form of the TNVS that can reduce pressure on its puny capabilities, but it cannot see its way through to embrace and guide the solution to its proper place in the Metro Manila transport system. Uber thinks the way to go is to ride on its popularity and public support to push the envelope by enlisting and deploying drivers and cars to gain a reputation for performance, and call attention to LTFRB’s obstructionism that stems from its low institutional capacity and indecision.

On August 14, the LTFRB suspended the operations of Uber for its defiance in continuing to register drivers. The defiance continued on the day the suspension order took effect, when Uber pulled a stunt — telling its drivers and the public that the suspension is not yet in effect because the firm submitted a motion for reconsideration to LTFRB. Predictably, LTFRB denied the motion.

Next, the LTFRB agreed to Uber’s offer to pay a fine to resume operations – but instead of the Uber offer of PHP10 million, LTFRB asked for PHP190 million. LTFRB computed the amount based on the estimated PHP10 million a day earnings of Uber and multiplied it to the 19 days remaining in the suspension period. But payment of the fine does not yet get Uber off the hook. Uber has to show proof that they extended financial assistance to their drivers in the total amount of PHP299,244,000.

It is revealing that Uber accepted the fine, and with the required financial assistance paid nearly half a billion pesos. It is clear that the potential earnings from Uber operations dictates making peace with LTFRB to be the most rational choice for the firm. How Uber becomes even more aggressive in its profit-making operations as a result of this denouement remains to be seen.

Apart from a vengeful exaction of a hefty fine (and making it publicly known that the members of the LTFRB are not pocketing the money), the LTFRB does not seem to be exercising strategic sense. Instead of collecting a fine that goes straight to the National Treasury, the amount could have been retained in the transport management sector to address so many of the risks that the entry of Uber has spawned. Exacting behavior modification from Uber takes money. Why lose it to the general fund?

Disciplining Uber could mean addressing these concerns:

- How will Uber ensure that their drivers will continue receiving adequate income as competition among them, and with other TNVS drivers, heats up?

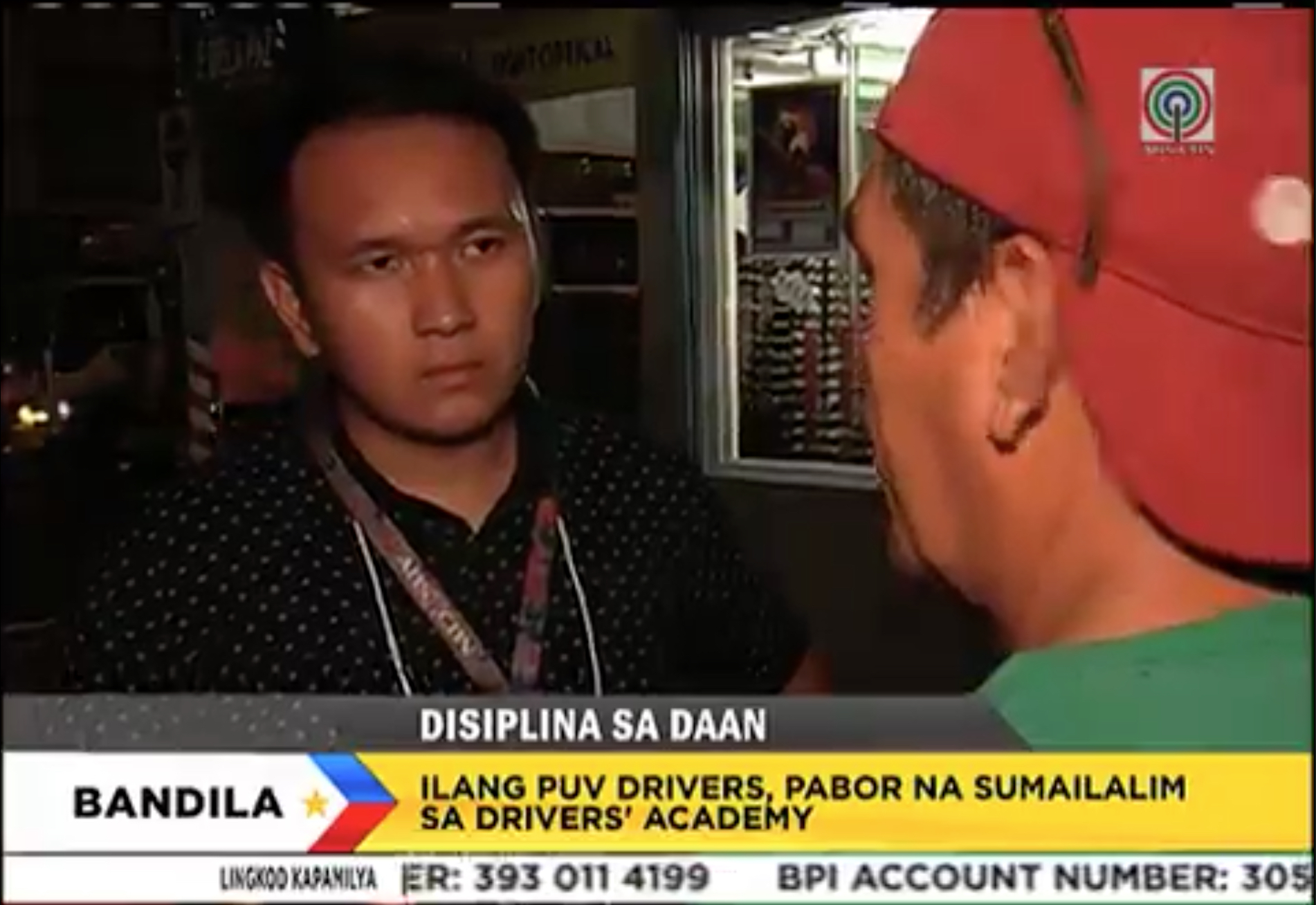

- .How will Uber ensure that drivers who work long hours to meet their quotas continue to drive safely, do not doze off while driving, and are not tempted to gyp their customers? In other countries, related complaints have come in the form of false driver reports that lead to “cleaning charge”, “waiting charge”, “cancellation charge.”

- How will Uber ensure that customers have a way of giving feedback, filing complaints, getting satisfaction from Uber? In other countries, dissatisfaction with Uber takes the form of complaints that Filipinos routinely level against their telcos — unwarranted, unjustified, and unilaterally imposed additional charges, difficulty to contact by phone or email, lack of responsiveness to complaints and feedback, opaque systems and procedures.

- How will Uber ensure that it shares and takes responsibility for deaths, injuries, damage to property, and crimes (rapes, kidnapping) that results from the operation of cars and drivers deployed in its name?

- How will Uber ensure that it will exercise corporate social responsibility (regard for people and planet aside from profit), and will not use its global corporate clout on the weak Philippine enforcement and judicial systems to escape responsibility?

- How will Uber moderate its corporate “greed” and be responsive to all its stakeholders in the realm of corporate culture and practice?

At the moment, Filipinos are optimistic about Uber. In the context of Metro Manila traffic, it is one of the solutions. But solutions in the Philippines (like ill-considered public policies) tend to become problems bigger than the solution.

It is ironical that the people’s “enemy” now — LTFRB — is the main regulator that will have to ensure that Uber over the long run will serve the Filipino people. Indeed, over the long term, Uber may turn out to be the Goliath to be slayed by LTFRB as David. Unfortunately, as the fine-imposition incident shows, it is not clear whether LTFRB will ever learn to use its slingshot properly. Before it can cut down Goliath to size, it must first win the trust of the public. At the moment, the public is cheering for Goliath.

(The author, Dr. Segundo Joaquin E. Romero, Jr. is a convenor of the Inclusive Mobility Network and Professorial Lecturer at the Development Studies Program of the Ateneo de Manila University)