On the 71st anniversary of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, forced disappearances, torture and prolonged imprisonment for one’s political beliefs remain constants of contemporary life. One imagines the original signatories of the declaration rolling in their graves and weeping, if that were possible, at the continued exercise of wars and injustice.

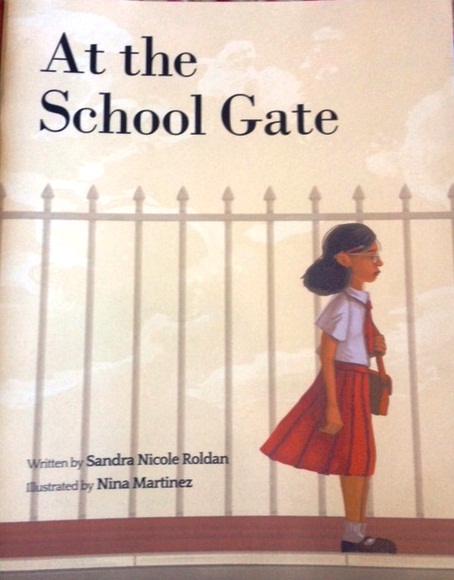

A slim book published by Bookmark, At the School Gate, authored by Sandra Nicole Roldan and illustrated by Nina Martinez, covers all the rights people need to uphold. It opens with a 15-year-old protagonist Ella Cortez trying to meet a deadline for a school paper and goes on to follow her as her aunt fetches her at the gate and breaks some somber news—the arrest of Ella’s father, an NGO worker.

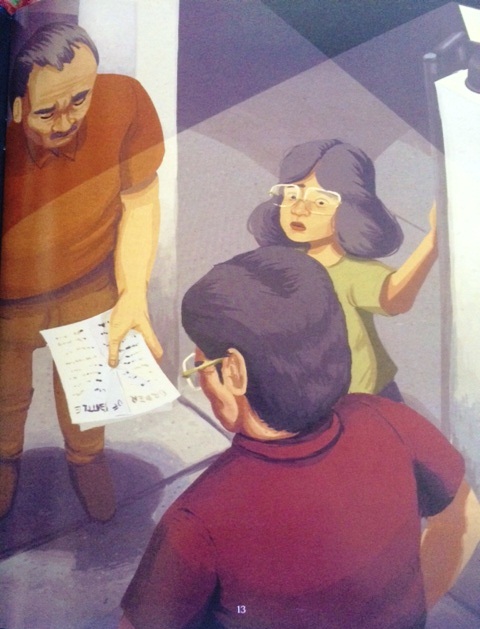

Illustration from At the School Gate

Her Papa’s history is one of activism during the First Quarter Storm, facing arrest and being jailed twice during martial law. From him Ella learns this lesson: “As long as you see something wrong, you don’t stop fixing it. You never really stop fighting. You just learn to fight in a different way.”

Even upon his release, the Cortez family, not intimidated by fascist forces, expresses their support for advocates of change by hosting meetings in their home, even giving these activists food, shelter and rest for the night. Ella is forced to grow up when her mother leaves for the US and her father takes on the job of a documentary filmmaker that brings him on long out of town sorties.

The child learns to transact with banks, settle bills, buy groceries, do the laundry, cook, etc. As she put it, “It’s not that hard, actually. Just speak in a deep voice and look serious all the time. It also helps to wear glasses.”

His father appears in the military’s Order of Battle. Sufficiently warned by a sympathetic relative in the army, the father goes into hiding, moving from house to house but still remembering to drop pasalubong for his family. He is eventually arrested, needless to say without a warrant or given the right to an attorney.

The family learns of his arrest when he is presented as a prized catch by the military on TV news. He is shown wearing a long-sleeved shirt, a way to hide the marks of torture during interrogation.

As is the military’s wont, Buggy Cortez, the father’s name, is slapped with charges of carrying an unlicensed .45-caliber pistol and subversive documents.

Ella is thrown into confusion. She asks the other adults in her extended family, “He didn’t do anything, right? He’s legal na, diba? No longer underground?”

She and her aunt also encounter a military man in civilian clothes who shadows them and smirks at them knowingly. The aunt explains this form of torture: “During martial law your Papa told me They did this as a form of psychological torture. They know where your loved ones are, what they do, what they wear to school. They can do anything to your children and no one will know. You’re helpless because you’re locked up. It’s worse than the water cure.”

Towards the end of the story—although this is fiction it resonates with the harsh light of truth in the real world—Ella musters enough courage to confront the soldier and even the school community.

The illustrations of Martinez are on the dark, brownish color scale that adds a strong air of foreboding to the story. The only hints of bright colors appear on the page when soldiers raiding the Cortez home let loose from an aviary a bunch of pet love birds in “lemon yellow, bubblegum pink, pale blue, tangerine and lime green feathers.”

This book deserves a wide readership not only among human rights supporters but also the bigger demographic slice that remains ignorant of the excesses of the Marcosian martial law and similar despotic regimes. There are hundreds of thousands of students out there, many in their college years, who have been conditioned to think that the Marcos years were the best for the Philippines.

At the School Gate shows this assumption is a lie. All the more Bookmark should push this book in schools and libraries nationwide. Then maybe the need for a Universal Declaration of Human Rights will be internalized by an awakened population. It no longer has to be a world of Us against Them.