It’s all in the name, according to President Rodrigo Duterte.

The fact that the South China Sea is named such reflects the historical claim of China to it, he said.

STATEMENT

In an ambush interview April 27 at Malacañang, Duterte told journalists:

“They really claim it as their own, noon pa iyan. Hindi lang talaga pumutok nang mainit. Ang nagpainit diyan iyong Amerikano. Noon pa iyan, kaya (It goes way back. The issue just did not erupt then. What triggered the conflict were the Americans. But it goes all the way back. That’s why it’s called) China Sea… sabi nga nila (they say) China Sea, historical na iyan. So hindi lang iyan pumuputok (It’s historical. The issue just had not erupted then) but this issue was the issue before so many generations ago.”

Source: Transcript of ambush interview, April 27, 2017, Presidential Communications Office News and Information Bureau

FACT

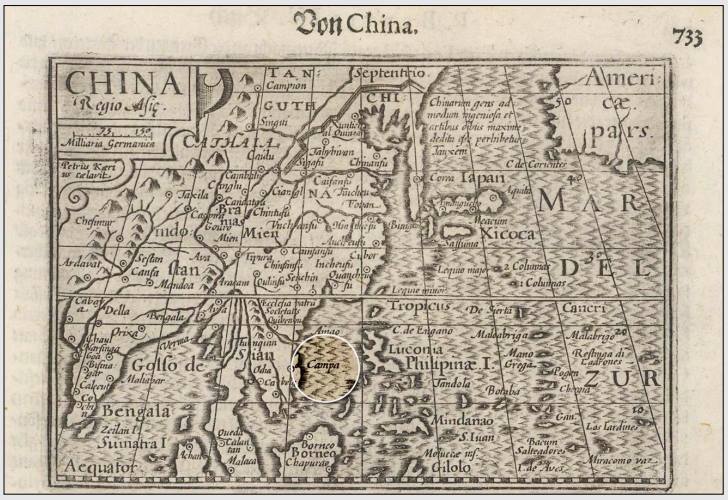

Contrary to Duterte’s statement, the body of water now commonly known as the South China Sea did not always have that name.

In his book The South China Sea Dispute: Philippine Sovereign Rights and Jurisdiction in the West Philippine Sea, Supreme Court Senior Associate Justice Antonio Carpio writes:

“Before Portuguese navigators coined the name South China Sea, the sea was known to Asian and Arab navigators as the Champa Sea, after the Cham people who established a great maritime kingdom in central Vietnam from the late 2nd to the 17th century.”

Carpio adds:

“The ancient Malays also called this sea Laut Chidol or the South Sea, as recorded by Pigafetta in his account of Ferdinand Magellan’s circumnavigation of the world from 1519 to 1522. In Malay, which is likewise derived from the Austronesian language, laut means sea and kidol means south.”

“The ancient Chinese never called this sea the South China Sea,” Carpio writes.

Their name for the sea was “Nan Hai” or the South Sea, he adds.

A paper by Zhiguo Gao of the China Institute of Marine Affairs and Bing Bing Jia of the Tsinghua University School of Law, published in the American Journal of International Law, also notes that Nan Hai is the standard name of the South China Sea in Chinese.

They write:

“The term Nan Hai (Southern Sea) appeared in the classic poetry book Shi Jing (The Classic of Poetry), a publication of the Spring and Autumn Period (475–221 BC), and it has remained the standard appellation in Chinese for the South China Sea ever since.”

In fact, “South China Sea” is a European name, coined in the early 16th century by explorers, notably the Portuguese.

The name, according to a chapter in the book Locating Southeast Asia: Geographies of Knowledge and Politics of Space, is:

“a relic of the time when European seafarers and mapmakers saw this sea mainly as an access route to China.”

Further, the book notes:

“The Portuguese captains saw the sea as the approach to this land of China and called it Mare da China. Then, presumably, when they later needed to distinguish between several China seas, they differentiated between the ‘South China Sea,” the ‘East China Sea,’ and the ‘Yellow Sea.’”

BACKSTORY

The South China Sea is a 3.5 million-square-kilometer expanse of water bounded by China/Taiwan in the north, by the Philippines in the east, and by Vietnam, Malaysia, Singapore, Indonesia, and Brunei in the west and south.

The Gulf of Tonkin and Gulf of Thailand also abut the South China Sea. Scattered over the South China Sea are various geographic features, the most prominent of which are known internationally as the Spratlys, the Paracels, Macclesfield Bank and Pratas Island.

The People’s Republic of China (PROC) claims almost 80 percent of the whole South China Sea with its controversial nine-dash-line map.

The Republic of China (Taiwan), which China considers its province, has a similar claim. Other Southeast Asian countries – Brunei, Malaysia, Philippines and Vietnam – also claim parts of the South China Sea.

Sources:

Antonio Carpio, The South China Sea Dispute: Philippine Sovereign Rights and Jurisdiction in the West Philippine Sea

Presidential Communications Office

Stein Tonnesson, Locating the South China Sea, in Locating Southeast Asia: Geographies of Knowledge and Politics of Space

Zhiguo Gao and Bing Bing Jia, The Nine-Dash Line in the South China Sea: History, Status, and Implications, The American Journal of International Law, vol. 107, no. 1, pp. 98- 124