When Pampanga Rep. and former president Gloria Macapagal Arroyo, former executive secretary Eduardo Ermita, and former solicitor general Estelito Mendoza launched a primer on the West Philippine Sea Thursday, the result was more confusion than clarity.

For one, Mendoza said there was no tension with China during the Arroyo administration, a claim that is not factual. (See VERA FILES FACT CHECK: No tension in South China Sea during Arroyo administration?)

What are the facts? Here are five. Generally, they show that issues surrounding the West Philippine Sea were an Arroyo problem, as much as they were Aquino’s and Duterte’s.

What do tensions in the West Philippine Sea have to do with the Arroyo administration?

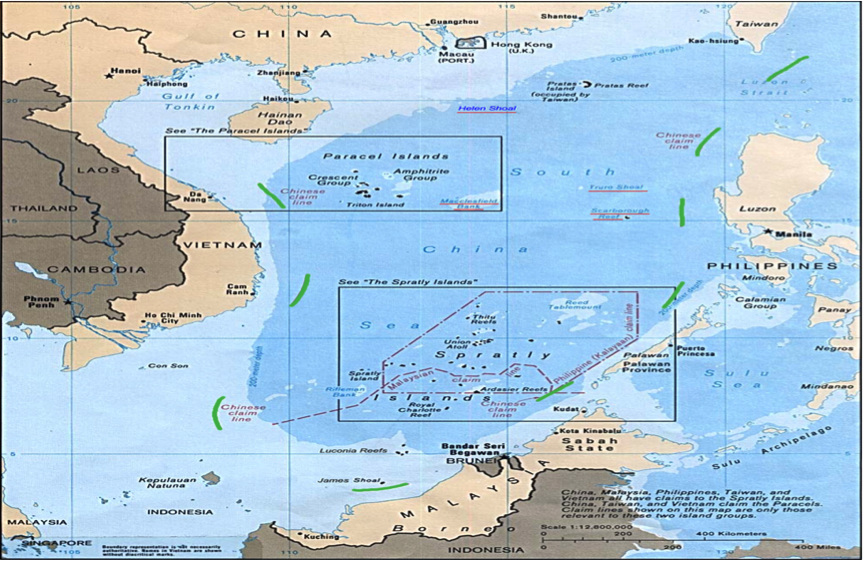

In 2009, Arroyo signed Republic Act 9522, which defines and describes the baselines of the Philippine archipelago. RA 9522 amended RA 3046, then the country’s baseline law, enacted in 1961. The amendment was to make the country compliant with the terms of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS).

What did Arroyo say about the law?

This is how the Philippine Star reported Arroyo’s comments at the press conference for RA 9522 in Malacañang:

“Arroyo also bragged about the fact that China ‘never questioned’ the Philippines’ Baselines Law (RA 9522) during her nine-year term that ended in June 2010.

‘China didn’t file a protest and they even recognized our 200-mile exclusive economic zone,’ Arroyo emphasized, affirming Mendoza’s position that only two areas were being claimed by Beijing then – Panatag (Scarborough) Shoal and Kalayaan Group of Islands.”

An unedited video of the presscon posted by Rappler, however, shows that Arroyo actually said:

“These are baselines. So China did not protest our drawing the baseline. But aside from the baseline, in another section of the law that we passed, we defined a regime of islands. So the regime of islands covered the Kalayaan group, and the Masinloc. So China did not protest this (points to an area on the map), did not protest this (points to another area), it protested this portion (points at yet another area), in a way, because that was part of… together, it’s a regime of islands. That’s what China protested… and also protested the Bajo de Masinloc because part of it is… also outside the 200-mile continental… economic zone.”

(Source:

Rappler, Arroyo press conference on West Philippine Sea, watch from 15:45-16:42)

What are baselines, and why do they have to be defined?

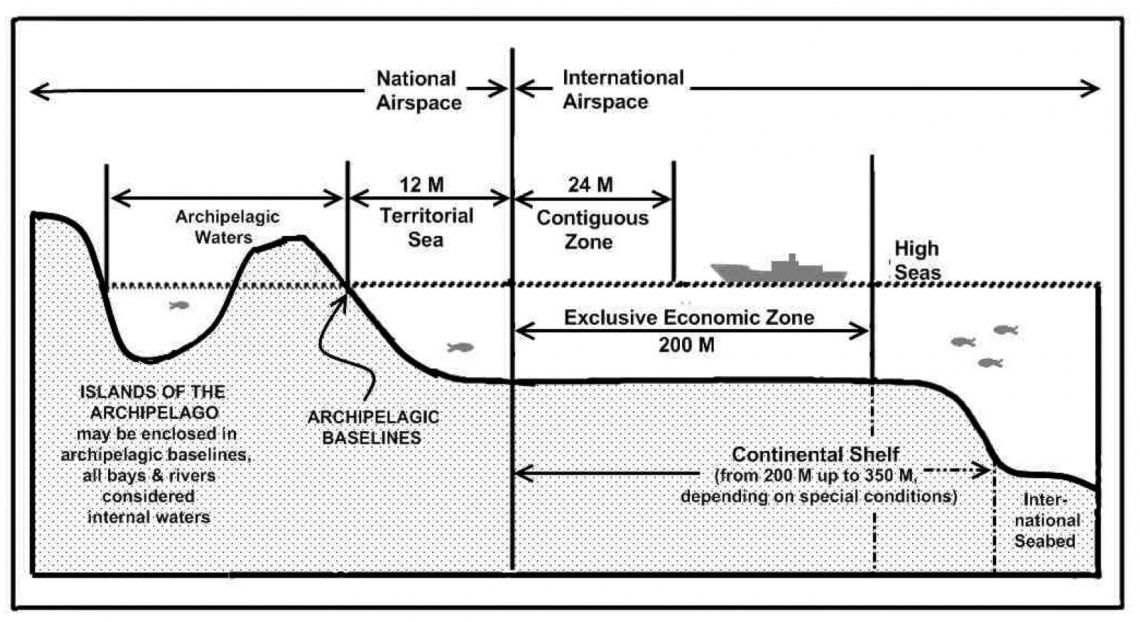

The late Sen. Miriam Defensor Santiago, the principal sponsor of RA 9522, offered this simple definition of baselines:

“Under international law, the baseline is the line that divides the land from the sea, by which the extent of a state’s coastal jurisdiction is measured.”

Maritime zones, and the country’s sovereignty over them, consist of the following:

UNCLOS maritime zones (Source: The West Philippine Sea: A Territorial and Maritime Jurisdiction Disputes from a Filipino Perspective)

UNCLOS maritime zones (Source: The West Philippine Sea: A Territorial and Maritime Jurisdiction Disputes from a Filipino Perspective)

Santiago further noted:

“It is only by defining our baselines that we can ensure acceptance of our maritime zones by all other states.”

What happened after RA 9552 was passed?

China protested the inclusion of Bajo de Masinloc and parts of the Kalayaan Island Group in the act, which it said it has “indisputable sovereignty over.” More, it called the act “null and void.”

In its letter to the Secretary-General of the United Nations, China said that RA 9522:

“…illegally claims Huangyan Island (referred as ‘Bajo de Masinloc’ in the Act) and some islands and reefs of Nansha Islands (referred as ‘The Kalayaan Island Group’ in the Act) of China as ‘areas over which the Philippines likewise has sovereignty and jurisdiction.’ the Chinese Government hereby reiterates that Huangyan Island and Nansha Islands have been part of the territory of China since ancient time. The People’s Republic of China has indisputable sovereignty over Huangyan Island and Nansha Islands and their surrounding maritime areas. Any claim to territorial sovereignty over Huangyan Island and Nansha Islands by any other State, is therefore, null and void.”

Taiwan and Vietnam also protested RA 9522.

The law also faced domestic opposition. Several law professors and law students questioned the constitutionality of RA 9522 before the Supreme Court, arguing that it reduces Philippine maritime territory and opens its waters to maritime passage by vessels and aircrafts.

The Supreme Court dismissed the petition in 2011.

What is a reliable source for more detailed information on the West Philippine Sea?

“The West Philippine Sea: The Territorial and Maritime Jurisdiction from a Filipino Perspective” is a primer which provides useful information on the issue. It discusses, among others, the difference between the West Philippine Sea and the South China Sea. A copy is available online.

VERA Files also monitors and fact-checks claims by public officials related to tensions in the West Philippine Sea. Some of the recent reports include:

Sources:

Philippine Star, GMA blames Noy for South China Sea problem, April 21, 2017

Rappler, Arroyo press conference on West Philippine Sea, April 20, 2017

Senate of the Philippines, Sponsorship speech on The 2009 Baseline Bill, January 27, 2009

Northeast Asian Perspectives on International Law: Contemporary Issues and Challenges

Supreme Court of the Philippines, G.R. No. 187167, Merlin Magallona, et al. v. Eduardo Ermita, et. al., July 16, 2011