Plaza Moriones, the newly rehabilitated expansive space leading to the iconic, 428-year-old Fort Santiago in Intramuros, Manila, has been artist Carlos Celdran’s favorite punchline lately.

“It’s flat, anonymous and it has nothing to do with Intramuros’ character or history,” Celdran said, even calling it the “plaza from Trinoma.” Trinoma is a shopping mall in Quezon City.

Known for his theatrical walking tours of Old Manila, Celdran also said Intramuros Administration (IA), the government entity in charge of the reconstruction, didn’t conduct enough public consultations on the makeover.

STATEMENT

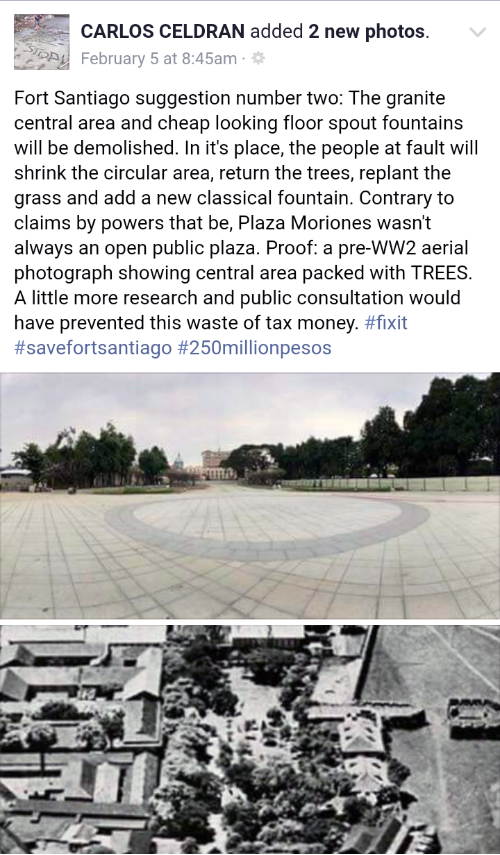

“Contrary to claims by powers that be, Plaza Moriones wasn’t always an open public plaza. Pre-WW2 aerial photos show central area packed with TREES. A little more research and public consultation would’ve prevented this waste of tax money. #fixit #savefortsantiago #250million”

(Source: Carlos Celdran’s Facebook page)

Screengrab from Carlos Celdran’s facebook page

Screengrab from Carlos Celdran’s facebook page

Celdran said the plaza’s design can still be rectified through public consultation and by returning more trees and reconfiguring the fountain in the middle to look less like a “fountain from Megamall,” another shopping center. If it were up to him, he would overhaul the entire thing, he says.

FACT SHEET

So why is the Plaza Moriones rehabilitation, and renewing heritage spaces for that matter, an issue? VERA Files looked into the matter and reached out to experts. Here are some facts about the historic site.

What is Plaza Moriones?

Plaza Moriones was originally called Plaza de la Fuerza, or Plaza of the Fort, and was built as a military parade ground of Fort Santiago.

The Fernandez de Roxas topographic map of Intramuros in 1714 shows stick figures in Plaza Moriones, which represent a group of soldiers in formation.

In 1863, an earthquake severely damaged Fort Santiago and the plaza was used as military barracks. In the late 1800s, Plaza de la Fuerza was renamed Plaza Moriones after Domingo Moriones, the Spanish governor general from 1877 to 1880.

During the American period, Fort Santiago became the headquarters and administrative offices of the United States Army.

American anthropologist Henry Otley Beyer, in a manuscript he wrote in the 1930s, said the US Army eventually took over Plaza Moriones and built soldiers’ quarters there.

How did Plaza Moriones look like then?

“It was built as a (military) parade ground and therefore a completely empty space,” says former IA administrator Jaime Laya in an interview with VERA Files.

John Arcilla, history researcher and planning officer of IA, says it was important for the space surrounding Fort Santiago to be unobstructed, as protection from enemies.

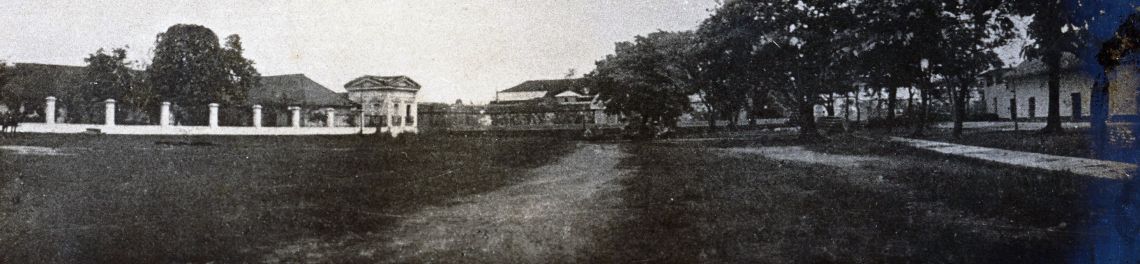

In 1903, during the early years of the American colonization, Plaza Moriones remained an open area with trees on the side.

Plaza Moriones in 1903, facing north. The Fort Santiago gate is partly hidden behind the trees.

How the plaza looked like in the succeeding decades before World War II broke is unclear.

In an email to VERA Files, the United States National Archives Records Administration said it has no images of Plaza Moriones during the American army’s stay at Intramuros. “None of the drawings in our holdings show the area outside of the fort,” it said.

In the book Intramuros: A Historical Guide, published in 1980, Plaza Moriones was described as “bare except for its grass cover in the last centuries.”

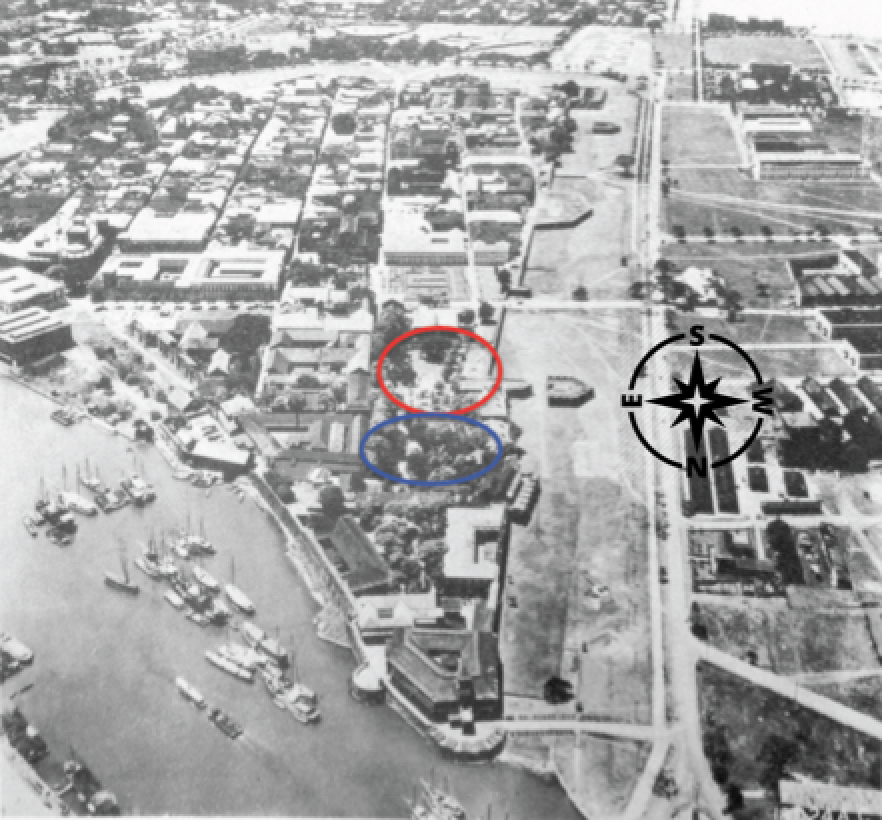

The photo Celdran posted in his Facebook account was an aerial shot of Intramuros circa 1930s. According to the book In & Around Intramuros: An interactive guide, the photo was taken from the United States National Archives Records Administration.

In the photo, Fort Santiago and Plaza Moriones can be seen from afar. It shows the southern part of the plaza as an open space, but with trees abounding in the northern part, just in front of the Fort Santiago gate.

Aerial view of Intramuros circa 1930

After World War II, Intramuros became a wasteland, almost all buildings in the walled city were destroyed.

It took decades before Intramuros was restored. Plaza Moriones looked like a “park with an expanse of green grass,” according to the book Walking Tour of Historic Intramuros published in 1971.

In the 1980s, Plaza Moriones began to look more contemporary, with concrete paths surrounding the grassy open space and a fountain in the middle.

Plaza Moriones in 1983

In 1993, a garden was placed in the central portion of the plaza, showcasing “flora typically found in 19th-century gardens.” This was how Plaza Moriones looked like until its rehabilitation last year.

Why was it rehabilitated?

Arcilla says the “relandscaping” of Plaza Moriones seeks to honor the military heritage of Fort Santiago by making the design more accessible to everyone, “more contextual and historically accurate, while at the same time trying to maintain green(ery).”

“The green is still there, kumbaga tinabi lang namin (we just moved them to the side). It was refreshing to look at kasi maraming halaman pero (because there were lots of plants but) you can hardly do anything with it. When you put an open space in the middle, you can do a lot more. Kasi (because) the sight line is important. Malayo pa lang, kita mo na ang (Even from afar, you can see the) Fort Santiago gate,” he adds.

Present day Plaza Moriones

IA, an attached agency of the Department of Tourism, was created to restore and develop Intramuros as a “monument to the Hispanic period in Philippine history.” One of its mandates is to ensure that the general appearance of Intramuros conforms to the Philippine-Spanish architecture in the 1500s to 1800s.

The IA envisions Plaza Moriones as a venue for heritage and cultural events. As stated in the plan provided to VERA Files, its rehabilitation is one of 10 such activities being done inside Fort Santiago, with a total budget of P240 million.

These are part of a long-term plan conceived in 2014 to revive the walled city to raise its land value, draw in investors and increase foot traffic.

Tourism Secretary Wanda Teo said one of the department’s priorities is the redevelopment of Intramuros. Since last month, visiting hours at Fort Santiago have been extended to 9 p.m. to accommodate more tourists.

Why were there no public consultations?

Public consultations are not part of the IA’s mandate, Arcilla says.

He however emphasized that IA consulted landscape architects and heritage experts at the project’s inception in 2014. “Hindi naman ito parang idea lang ng (It’s not as if it were solely the idea of) Intramuros Administration,” he adds.

In many countries, consultations are required before beginning any public project, including development of heritage sites, said architect Augusto Villalon, one of the experts consulted by IA. VERA Files tried to get Villalon’s statement on the matter but he did not respond. He however wrote about it later in his column in the Inquirer.

“The consultation method brings the decision-making to the ultimate user of the public space, to the community. The consultation procedure reverses the old top-down method that we have become used to—of the government, taking the position of the ‘owner’ of the public space and deciding by itself what is best for the people.” (Inquirer.net, Updating Plaza Moriones in Intramuros, March 6, 2017)

Villalon also said Plaza Moriones “might have turned out better designed than what it presently is,” had consultations been made with the users of the plaza.

Celdran says IA missed the way of life and on-the-ground ways of using space because it failed to consult the public from the start.

“If (IA) actually had talked with the people earlier, they would’ve found out that… they shouldn’t have torn down the bathroom without building another one. They shouldn’t have torn down the office of the administrators without providing another one. Or that you shouldn’t take out the trees because it makes it hot,” he says.

Laya, who co-authored the book Intramuros of Memory, explains how restorers work on a heritage space:

“The use and appearance of open spaces change over the years, over the centuries in this case, and restorers have to make a deliberate decision as to what cutoff point they will use for restoration purposes.”

Sources:

Carlos Celdran’s facebook page

Inquirer.net. Updating Plaza Moriones in Intramuros, March 6, 2017

Torres, J. (2005) Ciudad Murada: A walk through historic Intramuros. Manila: Intramuros Administration

Javellana, R. (2003) In & around Intramuros: An interactive guide. Quezon City: Jesuit Communications Foundation, Ateneo de Manila University

Gatbonton E. (1980) Intramuros: A historical guide. Manila: Intramuros Administration

Cushner, N. (1971) A walking tour of historic Intramuros. Quezon City: Alemar-Phoenix

Beyer, H. A brief history of Fort Santiago, with historical notes on the old Walled City of Manila

Intramuros Administration Archives