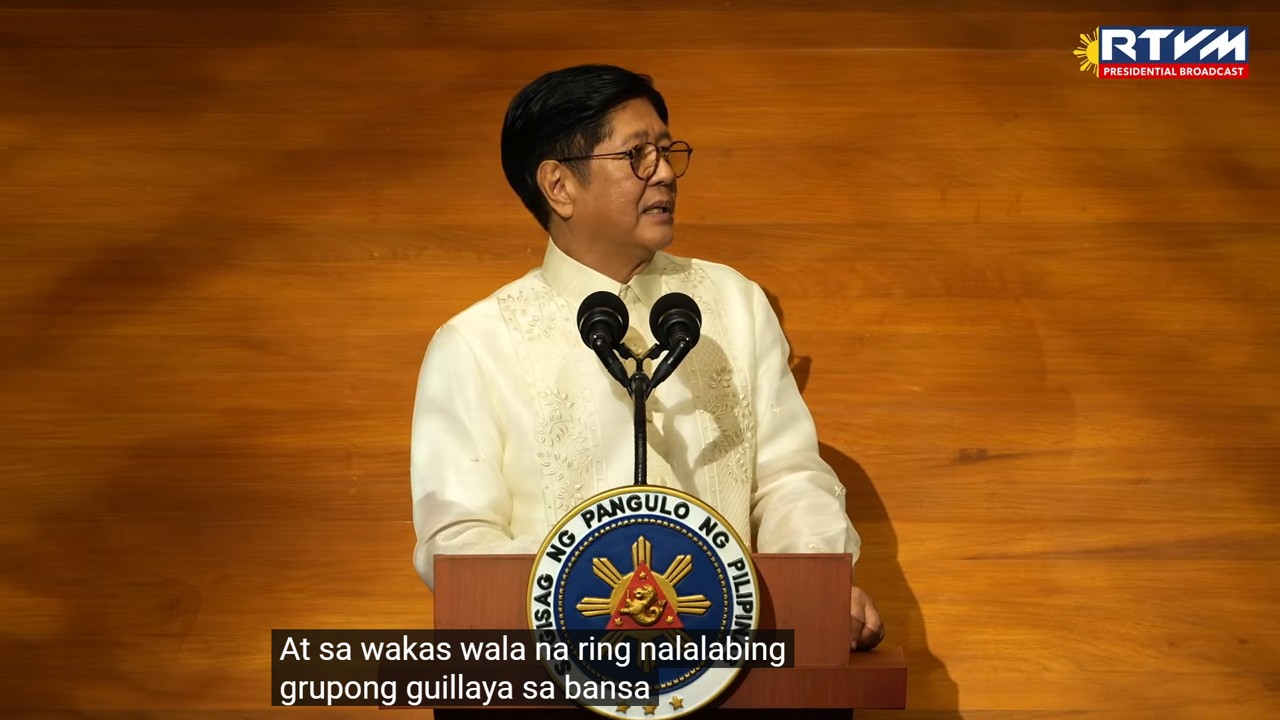

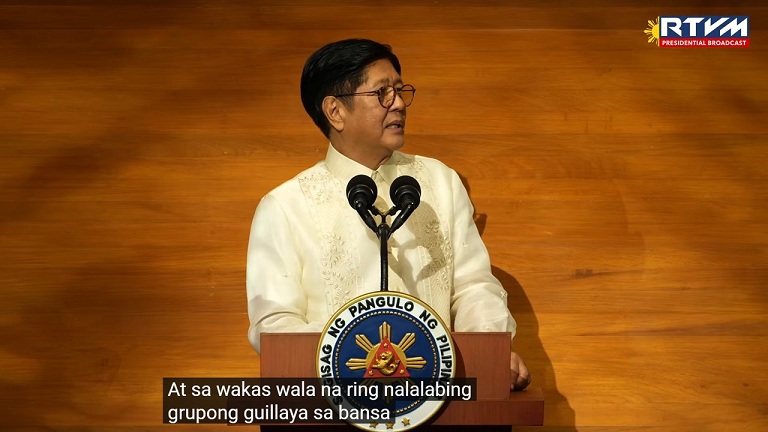

“Wala na ring nalalabing grupong gerilya sa bansa, at titiyakin ng pamahalaan na wala nang mabubuo muli,” (there are no more guerilla groups in the country, and the government will ensure that none will form again) intoned President Ferdinand “Bongbong” Marcos Jr. in his latest state of the nation address delivered on July 28. At first glance, this statement seems very similar to what he said in his SONA the year before:

No guerilla fronts remain active across the country today. Only seven weakened groups remain to be dismantled, and they are the subject of focused operations. But along with the assertion of government might, we also offer peace, community development, and reintegration programs for those who have returned to the fold of the law.

But Marcos’s more recent declaration seems both more disingenuous and more truthful: the Communist Party of the Philippines-New People’s Army (CPP-NPA) definitely still exists—Armed Forces of the Philippines Chief of Staff Gen. Romeo Brawner Jr. estimates that they have less than 900 fighters left—and, in an attempt to make sure that the “dead” insurgency is not resurrected, state forces, principally the AFP, are employing lethal force to exterminate what it calls the “Communist Terrorist Group.”

Indeed, fact-checking the president’s claim, Philstar.com noted that there were still armed clashes occurring between the CPP-NPA and the AFP, including two in Northern Samar that happened days after the SONA, resulting in eight rebel deaths. The Sandatahang Dahas monitor of the University of the Philippines Third World Studies Center notes that between January to July, 81 alleged members of the CPP-NPA were killed in reported encounters with the AFP in eighteen provinces. One encounter occurred in Masbate a day before the SONA, resulting in the death of eight suspected rebels. Within August, so far, at least two reported encounters—one in Occidental Mindoro (province no. 19) and one in Quezon (province no. 20)—resulted in NPA fatalities. A July 2021 article described counterinsurgency efforts, which resulted in 42 deaths, from January to June of that year as “aggressive”; 62 alleged rebels were killed between January-June.

Besides these encounters, which will be discussed in more detail later on, there are other indicators that the government as a whole has not provided any clear evidence to support Bongbong’s sweeping statement. Both the president and his subordinates rely on terms and statistics that suggest near-decisive victory against the communist insurgency, even if the use of these may result in spurring on the rebels. Responding to the president’s statement, CPP-NPA spokesperson Marco Valbuena said that “the grand declaration of having crushed the people’s armed resistance will explode in Marcos’ face,” and “a new generation of young Red fighters continues to slowly rise among workers, peasants and petty-bourgeois intellectuals.”

“Weakened” and “Dismantled” fronts

Before proceeding further, definitions must be provided. Numerous sources—from former police chief, now senator Ronald “Bato” dela Rosa to the CPP-NPA’s Valbuena—agree that an NPA front is made up of at least three platoons, or approximately 100 fighters in total. The AFP, as quoted by the Philippine Daily Inquirer, considers a front to be “weakened” if “it can no longer implement its programs like recruitment and generating resources for the armed struggle.”

Meanwhile, a 2024 article from Negros Now Daily, which relayed statements from Lt. Col. J-Jay Javines of the Philippine Army’s 3rd Division, gives the following definition of a “dismantled” front: “its armed component has been reduced to 8 to 10 members [that is, less than half of the persons needed to make up a platoon], there is an absence of mass-based organizations and it no longer has influenced areas, and there is implementation of government projects and establishment of government territorial forces in its area.” Javines noted that the declaration of front dismantlement must be validated by the concerned AFP area or unified command—for instance, regarding cases in the Negros provinces, the Visayas Command or VISCOM—and the Joint Peace and Security Coordinating Council.

Javines also emphasized that “[declaring] a guerilla front dismantled does not necessarily mean that the military will stop its operations against the remaining rebels.”

Fluctuating front counts

Apart from his SONAs, Marcos has stated on at least one other occasion that the government is well on the way to ending the insurgency. In a January 2024 video, posted on various social media platforms, he declared, “maaari na nating maireport na wala nang active NPA guerrilla front as of December of 2023.” This declaration appears to have been based on the AFP’s December 31, 2023 media release, which stated, “The AFP has achieved a significant milestone by dismantling eight and weakening 14 guerilla fronts of the Communist Terrorist Group (CTG). As of December, there are no more active CTG guerilla fronts.” However, as reported by The Philippine Star, according to then Presidential Communications Office secretary Cheloy Garafil, “having zero guerrilla fronts means there are no more active NPA strongholds, but there are still communist rebels.”

Then on January 14, 2024, the AFP held their year-end command conference with BBM, their commander-in-chief. In a press release on the event, the AFP noted that there were still “11 weakened guerilla fronts,” and, according to Gen. Brawner, “there are still CTG formations, or small bands of stragglers, that are still trying to regroup, recover lost areas, and rebuild support systems.” Nevertheless, they did not think this information contradicted the president’s “no active guerilla fronts” statement.

Interestingly, though Marcos claimed that there were no active NPA fronts in his 2024 SONA, his President’s Report to the People for that year—released to coincide with the SONA—included a graphic (on page 150) stating that as of May 2024, there were nine remaining guerilla fronts, declining from 24 in June 2022, based on data from the Department of National Defense. The same graphic states that “CTG Affected Areas” at the time were reduced to seven, down from 815 at the start of Bongbong’s term; recall that NPA deaths have occurred in 20 provinces in 2025 as of this writing.

In summary, within January to July 2024, the number of guerilla fronts in the country, as claimed by the president and the AFP, went up from zero (active, no mention of weakened) to eleven (weakened), then down to seven (weakened), then up to nine (unqualified if active or weakened) then back to zero (active, plus seven weakened).

Then, a few weeks after the President’s 2024 SONA, National Security Adviser (NSA) Eduardo Año stated that there were still five weakened guerilla fronts; in November, according to Gen. Brawner, they were down to four. In December 2024, the AFP started saying that there was only one remaining weakened guerilla front (recall: equivalent to about one hundred fighters) in the country. National Security Council Assistant Director General Jonathan Malaya repeated this claim in March 2025.

“Zero Barangay Affectation,” “Insurgency-Free,” “SIPS”

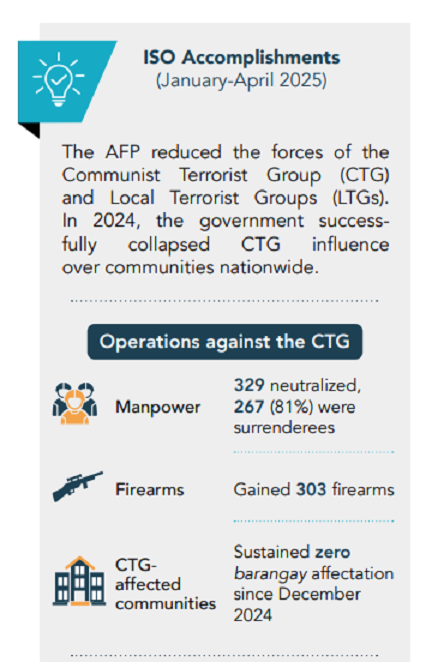

Bongbong’s 2025 Report to the People did not explicitly state that there were no guerillas left in the country, but an infographic on the document’s 157th page does state that in 2024, “the government successfully collapsed CTG influence over communities nationwide,” and, regarding a metric called “CTG-affected communities,” the Armed Forces were able to sustain “zero barangay affectation” since December 2024.

What is CTG or CPP-NPA “barangay affectation”? The term, sans CTG/CPP-NPA, is also used when talking about how much a barangay is affected by drugs (“affectation” being used to mean level of being affected, or “affected-ness,” as opposed to current dictionary definitions of the word, for instance, “a speech or conduct not natural to oneself” or “behavior or speech that is not sincere”). However, a spokesperson of the 3rd Infantry Division (operating in Negros) Maj. Cenon Pancito III, gave a somewhat different definition of the term back in November 2020: “Actually, barangay affectation is the behavior of a certain barangay towards the government. Ibig sabihin, pag na infiltrate ka, na influence ka, yung behavior ng community is not for the government but for the NPA.” This suggests that CPP-NPA barangay affectation can indicate both the influence of and sympathy for the rebels.

Barangay affectation can be tied to the notion of “insurgency-free” areas. The latter term has had several definitions. Back in the 2000s, when giving interviews, anti-communist hardliner (later convicted felon) Col. Jovito Palparan would use “insurgency-free” literally. That is, there is no CPP-NPA influence, activity, and presence in an insurgency-free area. In the lead up to the 2010 elections, the Army declared several provinces—including Cebu, Tarlac, Quirino, Surigao del Norte, Dinagat, Camiguin, and Misamis Oriental—as insurgency free; at least two of those provinces became host to AFP-NPA clashes this year. In February 2010, Capt. Adonis Bañez of the Army’s 5th Infantry Division said that the formal declaration of Apayao as insurgency free meant that in the province, the CPP-NPA’s armed component had already been “decimated” or can be considered “non-existent.”

Nowadays, being “insurgency-free” can be linked to the declaration of a locality as having Stable Internal Peace and Security (or SIPS) status. Many articles published in government news outlets say that an area can be considered in SIPS condition if there has been an absence of NPA activity therein for more than a year. A 2019 article published by the Philippine News Agency specified that “NPA activity” means “violent terroristic activity.” According to a February 2022 PNA article, Region I was the first to obtain region-wide SIPS status in February 2022, after “more than a year of zero violent incidents” involving the CPP-NPA in the Ilocos provinces.

A more recent article (April 2024) from the Philippine Information Agency states that provinces can be declared “in a state of SIPS” if they are considered “cleared, unaffected by communist insurgents and relatively peaceful.” The declaration is jointly made by the local government(s) involved and the Philippine National Police (PNP) and the Philippine Army. Interestingly, the same article noted that SIPS status is only one of the criteria for declaring an area insurgency-free—the two are not necessarily synonymous.

There is no source stating that the entire country, or at least a majority of its provinces, is in SIPS status or is already insurgency-free—not that saying either would mean that the NPAs are completely gone. Saying that there is “zero barangay CPP-NPA/CTG affectation” nationwide is also not the same as saying that there are no more guerilla groups in the country. Still, GenBrawner seconded his commander-in-chief in his July 30, 2025 Inquirer column, saying that the “’wala na ring nalalabing grupong gerilya’ milestone “came through years of persistence, dialogue, and shared sacrifice.”

Secretary Año, in a July 30 post-SONA discussion session, attributed the new condition to the government’s whole-of-nation and whole-of-government approaches, spearheaded by the Duterte-era creation called the National Task Force to End Local Communist Armed Conflict (NTF-ELCAC). He highlighted non-violent barangay development projects and peaceful surrenderers. He mentioned the possibility of turning over internal security concerns to the police, which, according to the law creating the PNP, should be primarily their responsibility. This transfer would free up the AFP to focus on external threats. However, though Año re-stated that there are no more active guerilla fronts in the country, he noted that there are still approximately 901 NPAs with more than 700 firearms, based on government estimates.

The NTF-ELCAC also affirmed the president’s 2025 SONA statement in a “FAQcheck press conference,” wherein they equated “wala [nang] grupong gerilya” with the oft-repeated “all [guerilla] fronts have been dismantled.” According to Army spokesperson Lt. Col. Louie Dema-Ala, the NPA had “lost [its] operational capability,” after the “neutralization or withdrawal of their armed units,” the “collapse of their political-military infrastructure,” the “loss [of their] mass base support,” the “denial of access to guerrilla zones,” and the “full reentry of government services in affected communities.” Differing from Año’s claim days before, NTF-ELCAC director Alexander Umpar claimed that as of August 4, only “around 785 armed NPA remnants,” still with more than 700 firearms, remained—suggesting that over a hundred rebels were “neutralized” over four days, though their arsenals were undiminished.

Concentration of Deadly Encounters

Based on government figures, there could have been nearly 2000 NPA members at the start of the year, assuming recruitment has indeed been practically halted; the AFP claimed that there were 2,112 rebels remaining in December 2022. As reported by GMA News, citing the AFP, from January 1 to July 24, 2025, 1,005 members of the “CTG” were neutralized—867 surrenderers, 71 apprehended, and 67 killed. But Gen. Brawner claimed that there were only around 1,500 NPA members at the start of 2024. If there are still 800-900 rebels left at the close of July 2025, then either estimates need to be reconciled or NPA recruitment by the hundreds still continues.

The AFP’s “CTG” kill count up to July 24 is the same as that of the Third World Studies Center’s Sandatahang Dahas. Even counting the two deaths that occurred in the first week of August, these killings resulted from engagements with soldiers under only four of the AFP’s seven area commands (as opposed to at least five in recent years). According to Sandatahang Dahas, many (39) of the killings thus far this year took place in the Visayas, mostly in the Samar-Leyte and the Negros Island provinces, which have long been insurgency hotbeds; VISCOM boasted that in 2023, 607 rebels were neutralized in its territory, 84 of whom were killed. Killings in 2025 in Negros happened every month from January to June, while NPA deaths occurred in Samar Island between February-March and May-July.

Clusters of killings also happened in the Agusan provinces from January-March and in June-July, extending to the neighboring Surigao provinces in May and June. The province where the most deaths happened in a single month is Masbate; in July 2025, two encounters, both tied to a pursuit of 15 rebels in the town of Uson, resulted in a total of nine deaths.

|

Region |

Alleged NPA Killed |

Specific Provinces (Killed/Province) |

AFP Area Command Concerned |

|

Region VIII |

25 |

Northern Samar (18), Leyte (3), Samar (3), Eastern Samar (1) |

Visayas Command (VISCOM) |

|

NIR |

13 |

Negros Occidental (11), Negros Oriental (2) |

|

|

Region VI |

1 |

Capiz (1) |

|

|

Region V |

18 |

Masbate (12), Albay (1), Camarines Sur (5) |

Southern Luzon Command (SOLCOM) |

|

Mimaropa (Region IV-B) |

1 |

Oriental Mindoro (1) |

|

|

Caraga (Region XIII) |

12 |

Agusan del Sur (4), Agusan del Norte (4), Surigao del Norte (3), Surigao del Sur (1) |

Eastern Mindanao Command (EASTMINCOM)

|

|

Region X |

3 |

Bukidnon (3) |

|

|

Region XI |

1 |

Davao Oriental (1) |

|

|

Soccsksargen (Region XII) |

7 |

Sultan Kudarat (7) |

Western Mindanao Command (WESTMINCOM) |

|

Total |

81 (January 1 – July 31, 2025) |

||

Another string of killings, from February-June, took place in Sultan Kudarat—the first, happening in Kalamansig town, resulting in one death, and the latest, again in Kalamansig, resulting in three fatalities, as well as the death of one AFP member. Overall, the pattern of deadly encounters suggests the AFP is relentlessly pursuing rebels, not giving retreating groups a moment’s rest. The military is partly aided by unmanned aerial drones, which have been in use against the CPP-NPA since the Duterte administration. (Repeatedly, instead of modern surveillance technology, the military claims that their counterinsurgency operations rely mostly on information from concerned locals or civilians, in keeping with the “zero barangay affectation” claim.) Clashes reported by the media tend to be initiated by the military, and often occur between nighttime and daybreak.

Deadly encounters between the AFP and the NPA in the Cagayan Valley happened annually between 2022 and 2024; thus far, there have been no such encounters in 2025—indeed, forces under the AFP’s Northern Luzon Command (NOLCOM) have not been responsible for any NPA deaths this year—though the military is still pursuing rebels in the area. In March 2025, the Philippine Army and the National Intelligence Coordinating Agency stated that the CPP-NPA in the Cagayan Valley was already “weakened.”

Thus, alongside calls to surrender and offers of “safe conduct passes” for rebels and assistance for reintegration (principally through the Duterte administration-initiated Enhanced Comprehensive Local Integration program, or E-CLIP), the military is projecting its ability to conduct successful manhunts, with hardly any casualties on their side. From January to July 2025, the media and the military acknowledged only four deaths of members of the AFP at the hands of the NPA, only one of which (in Samar) happened as a result of an ambush by the rebels.

In their releases through their official organ Ang Bayan and other outlets such as the Philippine Revolution Web Central, the CPP-NPA would claim otherwise, stating that they have killed numerous soldiers and police officers this year; many of their claims are difficult to corroborate, hardly being published in any venues other than the CPP-NPA’s. In contrast, many media outlets appear content to publish information on NPA killings provided by the AFP.

The preliminary count, using Sandatahang Dahas data, of 83 CPP-NPA killings as of August 2, 2025 is a few dozen shy of the AFP’s rebel kill count from January 1 to November 28, 2024—by that date, according to AFP spokesperson Col. Francel Padilla, 146 persons affiliated with the “CTG” had been killed.

Indeed, it will be unsurprising if a final tally of NPA members killed from June 2022 to this date will be in the 300-500 range. Under BBM, a ceasefire during the December holidays was declared by the rebels only once: in 2023, after an commitment made on Nov. 23 of that year between the National Democratic Front of the Philippines (NDFP), the CPP-NPA’s political wing—represented by party stalwart Luis Jalandoni—and the Philippine government to pursue “a principled and peaceful resolution of the armed conflict.” The 4th Infantry Division (under EASTMINCOM) did not honor the unilateral ceasefire, pursuing the NPA in four barangays in Bukidnon, killing nine on Christmas Day.

Considering all of the above, though he seems perfectly comfortable with exterminating the NPA by any means necessary, the president’s unqualified “wala nang grupong gerilya” statement is patently false—an exaggeration of claims, which are sometimes contradictory, by members of the defense establishment about the strength and influence of the communist rebels. Still, as other (external) observers have noted, since late 2024, the CPP-NPA may indeed be at their weakest point in decades. The government has partly attributed this to the recent deaths of key members of the CPP-NPA national leadership, including its founder, Jose Maria Sison (2022) and spouses Benito and Wilma Tiamzon (2022), CPP executive committee chairman and secretary general, respectively. Luis Jalandoni also died in June this year.

In a visit to the 203rd Infantry Brigade in Oriental Mindoro on August 14, Gen. Brawner said that they were close to signing a Framework Agreement that will cease the armed struggle of the CPP-NPA once and for all. In a statement released in September last year, Julie de Lima—Sison’s widow, chair of the NDFP negotiating panel—said that there were “ongoing talks” between her side and the Philippine government, “meant to come up with an agreed framework for the negotiations towards forging an agreement that will address the root causes of the armed conflict.” She noted, however, that her side was getting “mixed and contradictory signals” from the government, noting that NSA head Eduardo Año believed that “peace talks are unlikely to proceed.” Brawner’s recent statement suggests that an agreement was in development anyway, even if hardly anything has been heard from de Lima or the NDFP beyond a statement on the arrest of three NDFP consultants in October 2024, as well as the numerous fatal firefights have occurred between the AFP and the communist rebels within the last year.

Besides de Lima, no figureheads have emerged, perhaps giving further credence to the AFP’s claim that they are now dealing largely with NPA “stragglers” and “remnants,” whom committed soldiers are pursuing with all their might. If Asia’s longest-running communist insurgency does end under Marcos Jr.’s watch, that victory will not come after the peaceful surrender of (dead) rebel leaders—it will be drenched in blood.

Miguel Paolo P. Reyes is a university research associate at the Third World Studies Center (TWSC), College of Social Sciences and Philosophy, University of the Philippines Diliman. He is also a senior lecturer at the Department of English and Comparative Literature of the same university. Among TWSC’s main research endeavors are the drug-related killings monitor Dahas, the state-related violence monitor Sandatahang Dahas, and the Marcos Regime Research program.