“Making wars means making maps,” the Thai scholar Thongchai Winichakul wrote in his landmark Siam Mapped: A History of the Geo-Body of a Nation (1994). His words come to mind with the publication just a few weeks ago of China’s new 10-dash line map, seven years after the 2016 South China Sea Arbitral Award (AA) that invalidated its old Nine-dash line map.

Almost predictably, India, Vietnam, Malaysia and the Philippines filed salvoes against the new Chinese map. Consistent with its strategy of non-participation in the landmark arbitration, China is trying to solidify its legal position as a “persistent objector” to the ruling. But it is up against key doctrines established in the arbitral ruling.

Firstly, there is of course, the AA’s holding that the Nine-Dash line exceeds China’s maritime entitlements under the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). AA had ruled that the earlier Chinese line map was in the nature of an historical rights claim short of a territorial assertion. Well, the 10-dash line apparently goes beyond the former, as it now appears to mark out China’s territorial boundaries on most of the same areas covered by its predecessor, with a new 10th dash through the Bashi channel to the east of Taiwan.

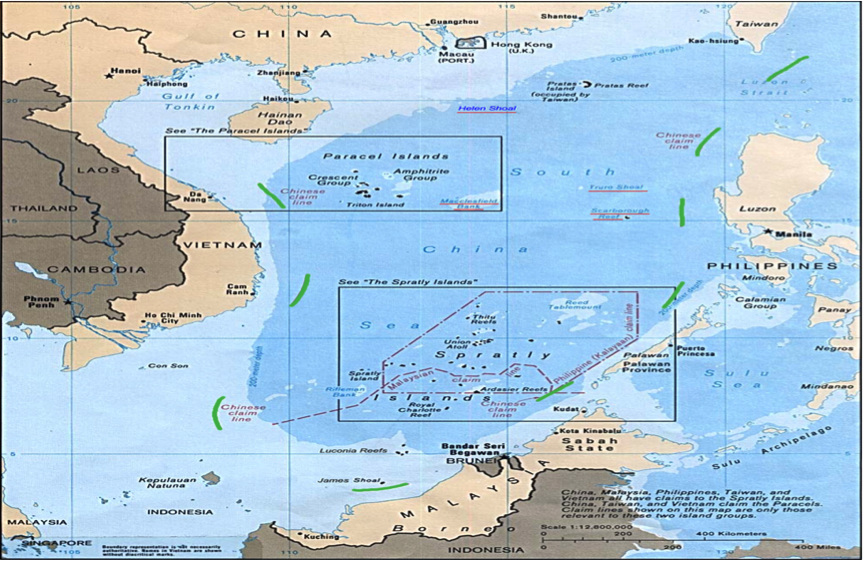

Secondly – and this is all AA too – no claimant state may constitute an offshore archipelago out of the Spratlys. If the new Chinese map is what it appears to be, then it is now a clearer map of a giant South China Sea archipelago, with the addition of the 10th line less than a 100 nautical miles off Taiwan, (which, by the way, ought to ring the alarm bells for everyone).

Thirdly, the AA also reduced the contending territorial claims to a questions of rocks or high tide elevations (HTEs) in the area, which are only able to generate a territorial sea (TS) and no more. Individual HTEs, not an entire offshore archipelago, nor portions of it constituted as offshore archipelagos.

If China thinks the new map evades the AA rulings, it’s obviously wrong on that point. The AA’s ruling that simplified the SCS claims into a matter of HTEs rather than the old archipelago-sized ones pre-July 12, 2016 (the date the AA was issued) is what scholars call the applicable “intertemporal law” to the yet pending territorial disputes in the region. Such (international) law, first enunciated in the landmark 1928 Palmas/Miangas Arbitration by Swiss arbitrator Max Huber, refers to the “rules determining which of successive legal systems is to be applied.”

In 1951, a landmark peace conference convened by the United States of America to determine the fate of the Spratlys gave birth to the San Francisco Peace Treaty. Art. 2(f) of the Treaty provided that “Japan renounces all right, title and claim to the Spratly Islands.” It considered the Spratlys as a single unit. But the AA changed all that. While the AA certainly did not cover territorial issues, it however split the Troung Sa/Nansha Qundao/Kalayaan Island Group (KIG) of Presidential Decree 1596 (1978) into individual rocks or HTEs, holding that neither the UNCLOS nor general international law supports an archipelago-like claim, in whole or in part, in the area.

Moreover, this has to be correlated with what Huber laid down in the Palmas Arbitration as the “critical date”: the point of crystallization of claims. The applicable critical date was reset by the AA from April 28, 1952, the date the San Francisco Peace Treaty took effect, to July 12, 2016, the date the AA was issued by the ad hoc Arbitral Tribunal. In other words, the legal treatment of the Spratlys as a unit or in archipelagic terms has been succeeded by the AA’s treatment of the area as consisting of individual rocks or HTEs.

In real terms, this means that each claimant state may now be able to establish that it has a title better than those of other claimants to each relevant rock or HTE (rather than to a group of HTEs or to an entire offshore archipelago) from that date onwards. That should have been enough prompt for the Philippines to consolidate title over each of the maritime features it occupies or claims through effectivités or acts of administration with intent to exercise sovereignty (Nicaragua v Colombia, 2012).

However, that it hasn’t done. Who has done so?

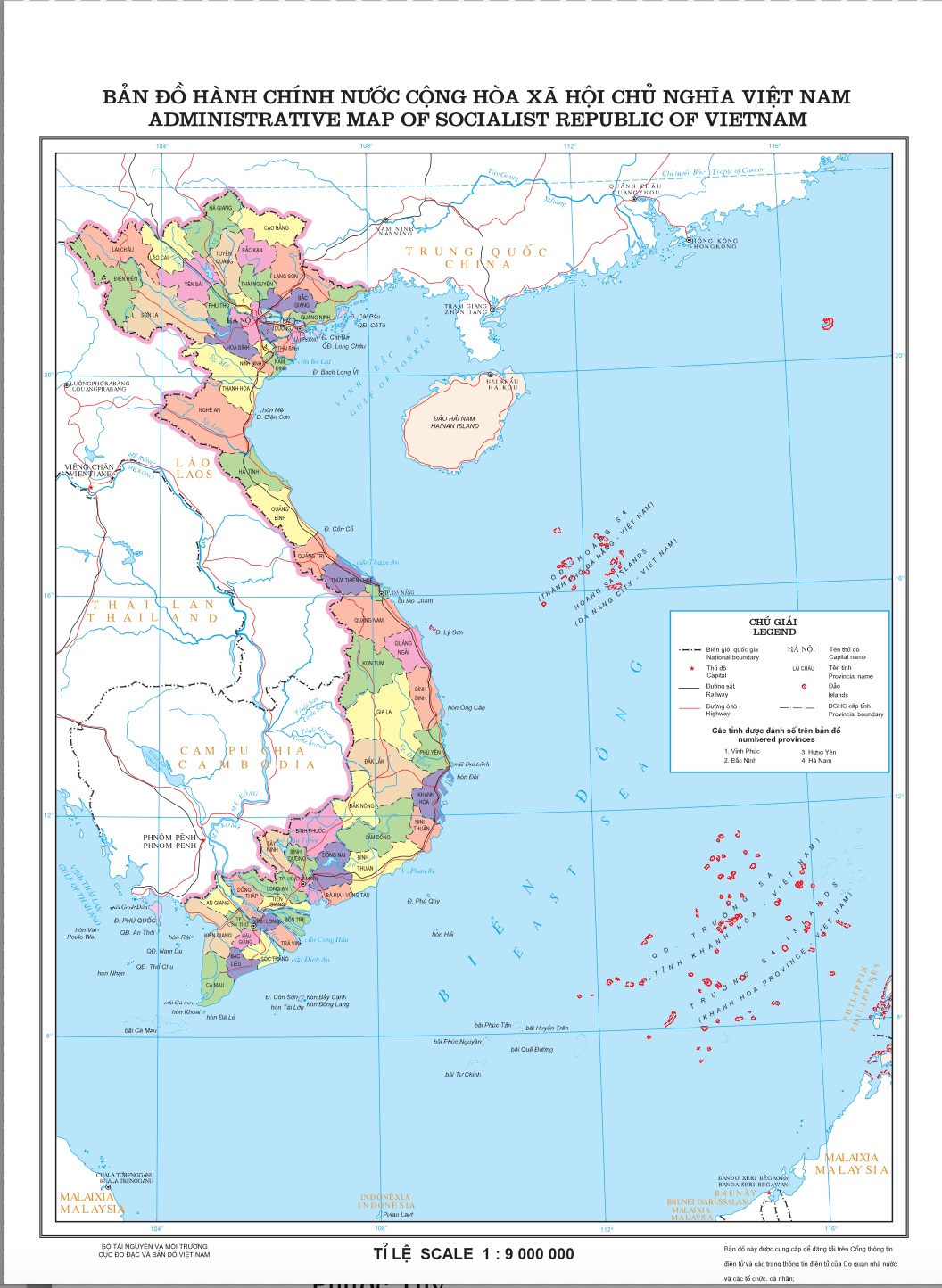

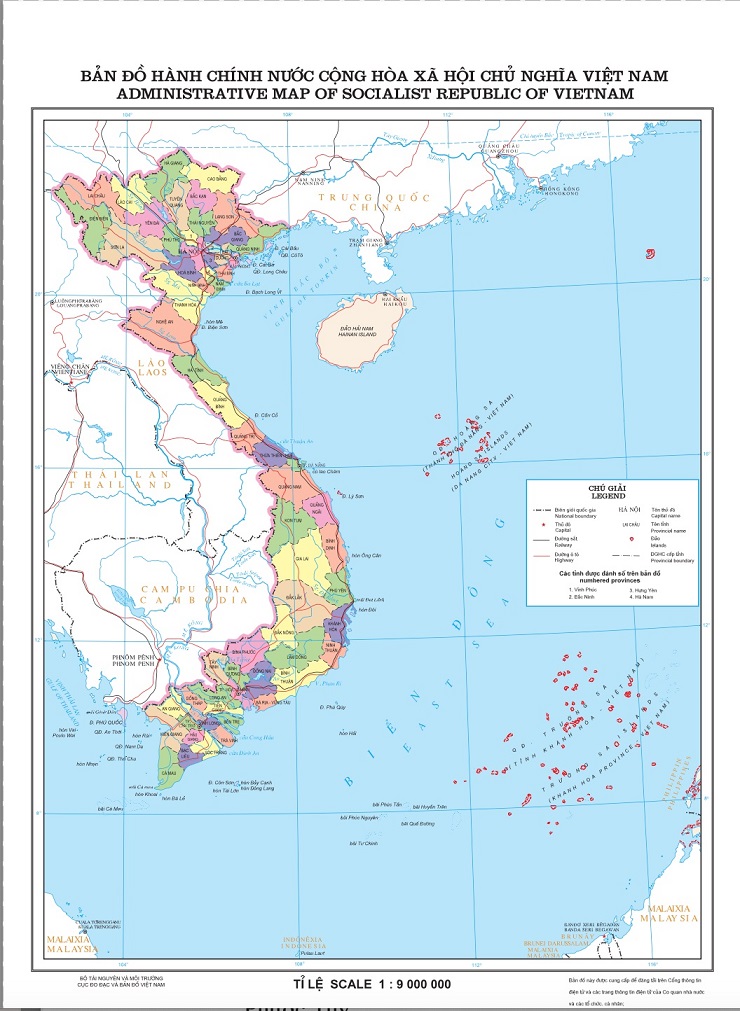

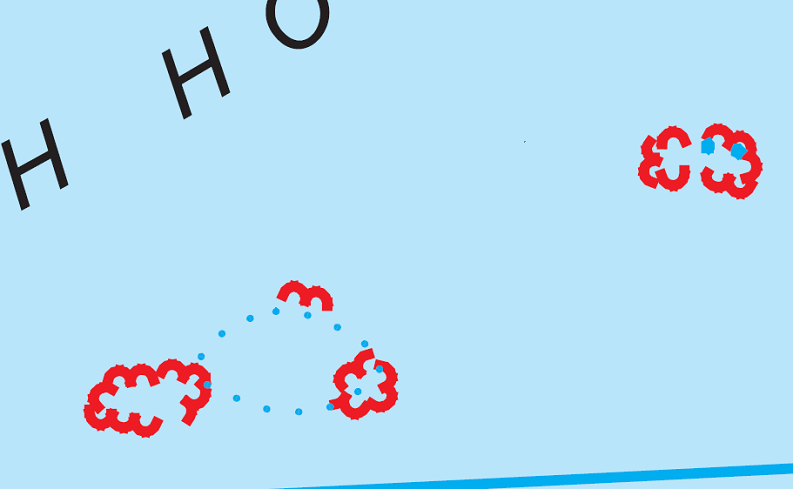

Quietly, and long before China made public its 10-dash line map, Vietnam published a new administrative map showing its Truong Sa claim (probably as early as October 2020, based on data from the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs), with the features within it ringed by what appears to be baselines. This is the first time any SCS claimant state has actually applied the lessons of the 2016 AA in that manner, that is, by drawing baselines around the features it claims to mark out the reaches of each feature’s territorial sea. A closer look at the “Administrative Map of the Socialist Republic of Vietnam” will reveal features embraced by Troung Sa offshore archipelagic claim now enclosed in red lines.

That these red lines are in fact baselines is indicated by the fact that there are features in Troung Sa that Vietnam did not enclose in the same lines. The latter appears to be low tide elevations that are not legal rocks. In other words, the blue dots with red lines in the administrative map are rocks/HTEs, while the blue dots without red lines are merely LTEs.

It is true that Vietnam has not yet made public nor filed with the UN Secretary General the coordinates of basepoints to the apparent baselines, but it has taken a step in the right direction.

The Palmas Arbitration itself has said as much 95 years ago: official maps are to “precisely indicate the political distribution of territories” and to make them “clearly marked as such”, otherwise, they are to be “rejected forthwith”.In addition, it also held that general maps are of less legal weight than particular ones.

Vietnam occupies 22 features in the area covered by the old KIG, namely Allison (De Jesus) Reef; Amboyna (Kalantiyaw) Cay; Barque Canada (Mascardo) Reef; Central London (Gitna) Reef; Collins Reef; Cornwallis (Osmeña) Reef; Discovery Great (Paredes) Reef; East (Silangan) Reef; Ladd Reef; Lendao Reef; Namyit (Binago) Island; Pearson (Hizon) Reef; Petley Reef; Pigeon/Tennent Reef; Sand Cay; Sincowe East Island; Sincowe (Rurok) Island; South Reef; Southwest (Pugad) Cay; Spratly (Lagos) Island; West (Kanluran) Reef; and Bombay Castle. In addition, its Troung Sa archipelago also claims a few larger features in the area occupied by the Philippines, including Thitu (Pag-Asa) island, Nanshan (Lawak)Island, Northeast Cay (Parola), and Loaita (Kota) Island. The Philippines has no claim over the Paracel islands.

Surprisingly, the Philippines has been all too quiet on this new Vietnamese map (perhaps, because the map has been surreptitiously published). The Philippines really shouldn’t be if it has at all learned the lessons of Palmas, a case in which its old colonial master, the United States of America, lost an island within the international treaty limits of the 1898 Treaty of Paris, to the Netherlands, the former colonizer of what is now Indonesia.

The intertemporal law on territorial claims now provide that these must pertain to a defined piece of land (or rock), from which maritime zones are then projected. It bears recalling that PD 1596 simply enclosed within baselines tacked to a leg of the old 1898 Treaty of Paris International Treaty Limits a huge area in the Spratlys, without specifically naming and identifying the features found there.

The US drew lines on the waters to enclose Palmas, as China is doing now with its 10-dash line map; the Netherlands performed acts of control specific to what it called the island of Miangas, as Vietnam is now doing by defining each feature of the Truong Sa and placing them under the province of Kuong Sa.

The Philippines, beyond protesting China’s 10-Dash line map or Vietnam’s new administrative map, should draw normal baselines to delineate the TS of each rock that it claims under its West Philippine Sea declaration; it may also even draw straight baselines drawn from low-tide elevations (LTEs) inside the TS (Nicaragua v. Columbia, 1986; and Qatar v Bahrain, 1995).

Why do we need to do this? Loja and Bagares (2021) have laid down four reasons for its urgency,

Firstly, pockets of rocks with their respective TS now bob in the Philippine Exclusive Economic Zone, with their own airspace over which full sovereignty may also be claimed. In other words, the rocks with their TS may also serve as a basis for declaring an Air Defense Zone.

Secondly, even RA 9522 (2009) compels the government to draw baselines around the features as a “regime of islands”. There is no regime of islands without baselines. The “regime of islands” under UNCLOS simply means that full islands shall have a TS, contiguous zone, EEZ, and continental shelf. Rocks shall have a TS while an LTE shall have no maritime entitlement at all. However, such regime presupposes that baselines have been drawn around the features. This, the proposed maritime zones law now pending in the Senate has not done.

The situation in Bajo de Masinloc is particularly dire, as the AA had declared its TS as subject to common fishing among Chinese, Vietnamese, and Filipino fishermen. Its TS needs to be clearly identified, to prevent such an artisanal fishing regime from spilling over into our EEZ.

Thirdly, China has taken advantage of our procrastination, freely moving within our EEZ as well as the TS of HTEs we claim or occupy, in the absence of formally drawn baselines pursuant to the AA. We must remember that baselines are a “precondition for our unhampered enjoyment of sovereign rights in the waters within our EEZ but beyond the TS of contested rocks.” On this point, consider how the Chinese navy, in coordination with its coastguard and militia, routinely swarms the territorial waters of our Pag-Asa island with nary a protest from us, until very recently. These swarming activities hardly qualify as innocent passage under customary international law and the UNCLOS).

Lastly, formally drawn baselines will also mean properly designated zones of maritime law enforcement and security. Our Coastguard and Navy, on that basis, may then be able to properly calibrate the appropriate level of force to use in each zone, should the need for it arises.

Without them, in the highly-charged atmosphere now obtaining in the SCS, they might – God forbid – be forced by circumstances to shoot blindly, or worse, spark a shooting war with nary a legal basis for it.

*The author teaches international law in three Manila-based law schools and the Philippine Judicial Academy.