“Seven years ago, I was an interesting person. Now I am a corpse,” lamented Benito Mussolini after his ouster and arrest, when he sensed the end was near.

When Rodrigo Duterte said he did not show up for work for two weeks only because of caprice, he broke the record of presidential secrecy on fitness for office. That record was previously held by the dictator Ferdinand Marcos, who not only had a kidney transplant in Malacañang, but who had also shat in his pants during his last days in office. The Marcos Malacañang was in an endless spin of tales about his state of health, a tradition confirmed by a utility-man-turned-senator whose Photoshopped pictures will hardly pass muster with Ripley’s Believe It or Not.

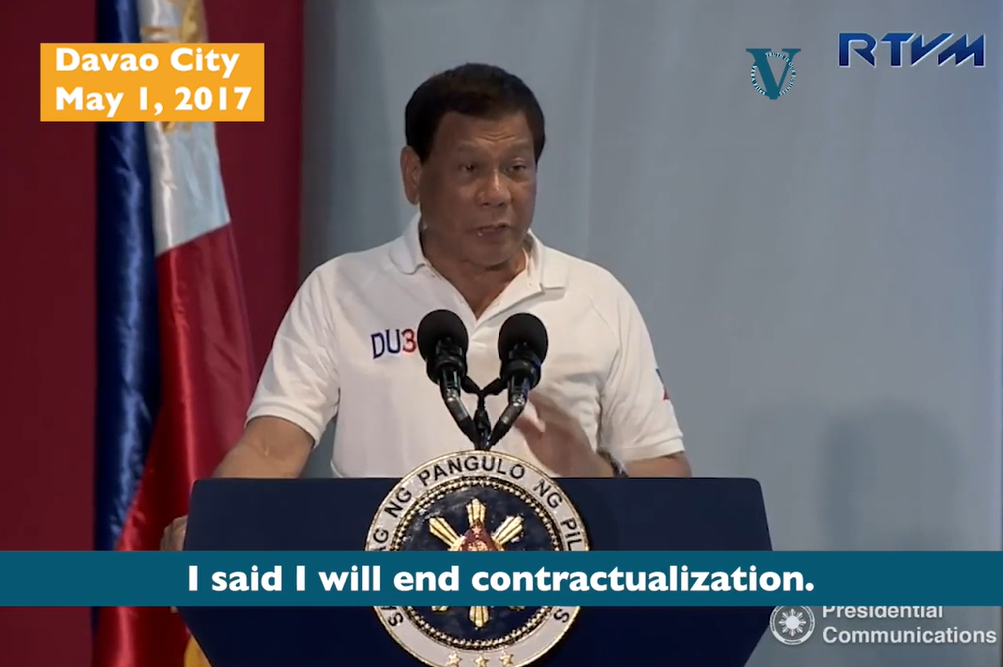

The brazen windbag Duterte wants us to spoil him in his geriatric years by evading any talk of presidential absenteeism or illness. It is an incongruence in a world of accessible communications. Simply, it has no place in a free democracy where attendance to work of the person we pay for the task is part of public accountability. He does not see that, of course, because Davao city had spoiled him and his family with that silly entitlement that happens only in bastions of juvenile democracy.

Perhaps all dictators feel they have become a corpse, like Mussolini did, in their last days in office – because the last days are days when dictators are threatened by the end of their power reign. The end of power is like a putrid cadaver: The dictator is bereft of dominion and lies vulnerable to answer for his misdeeds. Mortality issues are thus swept under the rug as secrets. But because secrets do not hide for long in a world of information gluttony, Duterte had better protect his legacy and his history by learning from the lessons of the Marcos dictatorship. One of the greatest worries of the Marcos children today, they once said in a television interview, is how time has censured the memory of their father and made him a freak of Philippine history. The dictator had only himself to blame for evading public accountability of his health.

Manny Alandy reminds me of a story documented elsewhere by martial law history books (The Marcos Dynasty, Sterling Seagrave) and by the world’s press. “Despite Marcos’s denial about his kidney condition and transplant, it was our family friend and neighbor in Cubao, Dr. Potenciano Baccay his nephrologist, who was murdered by his henchmen for divulging his condition.”

The Marcos police had disclosed to media that it was the “communists” who were behind the Baccay murder as a kidnap-robbery ploy. The Baccay neighbor Manny Alandy recalls: “The killers were waiting in his residence. He was found dead the next day with a gaping wound from his throat down to his stomach. He left a wife and very young children. This was a family of professionals with a well-balanced life: accomplished yet they lived very simple lives. This memory brings a bit of sadness. The family remained withdrawn after that.”

Marcos just kept on lying and lying and lying. The week of Dr. Baccay’s murder, he continued to deny he suffered serious ailments. In fact, it was soon after that when Marcos bared his shirt to show abs that had no scars from a kidney transplant surgery. But the media had included a disclaimer in the caption: “Several kidney specialists said scarring from surgery could be below the belt or out of view of the camera.”

Attending to the health care of presidential families was part of Manny Alandy’s family background. His late father was a personal physician to the Quezons. Dr. Luis Alandy was present in the convoy of Aurora Aragon Quezon the day she perished in an ambush in Bongabon, Nueva Ecija on April 28, 1949.

What happens to petty dictators who hide their fitness for office? They get deposed. For those lucky 60% who die of natural demise, a history of infamy awaits them after death. Duterte doesn’t really have much choice, and that’s why time is running out on his gangster governance. For sure he will be judged by a history narrative that will shout his name not with praise, but with derision as the worst and laziest president of the Philippines.

The views in this column are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of VERA Files.