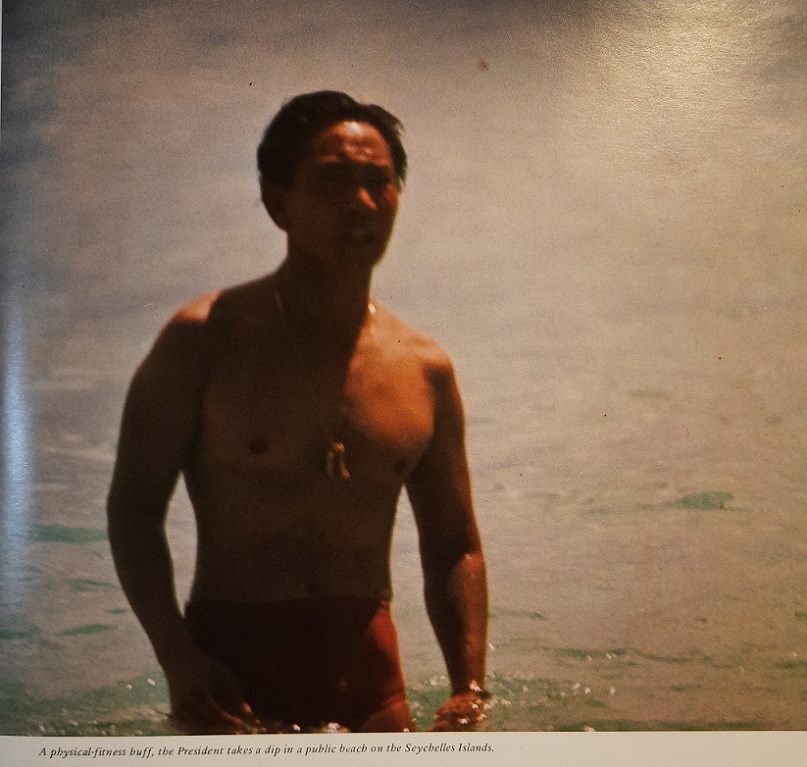

Marcos, physical fitness buff. Photo from The Marcos Revolution: A Progress Report on the New Society of the Philippines (National Media Production Center, 1980).

President Rodrigo Duterte’s frequent public disappearances followed by staged photos to dispel rumors about his health recall the waning years of the dictator, Ferdinand Marcos.

Despite widespread talk that Marcos was terminally ill, this was never confirmed by Malacañang Palace. But proof of the strongman’s grave illness was there for all to see when the first family fled the country in 1986.Discovered in Malacañang were five dialysis machines, emergency oxygen equipment, and a hospital bed. Among the luxury vehicles in the Palace garage was a 40-feet long, air conditioned, rainbow-colored hospital-on-wheels furnished with a kidney dialysis machine, x-ray equipment, a bed, and a kitchen.

American journalist Sandra Burton also found there a telltale sign: a copy of the “Handbook for Renal Transplant Outpatients.”

Duterte’s recent week-long absence from public view once again sparked speculation about the 76-year-old president’s health. Unlike Marcos, Duterte has never said he is free from any affliction, but insists he has no serious illness which the Constitution would require him to publicly reveal.

In truth, Marcos’ health problems trailed him to the presidency.

In Ferdinand E. Marcos: Malacañang to Makiki (1991), the strongman’s long-time military aide, Arturo Aruiza detailed almost all the maladies that tormented Marcos. Aruiza had access to the medical history of his boss, culled from reports of attending physicians to Marcos’s lawyers.

To begin with, Marcos had hemolysis (which destroys the body’s red blood cells) and hyperuricemia (high levels of uric acid in the blood).By 1979, his blood pressure was shooting up to alarming levels and he was showing signs of renal dysfunction as well as problems with his heart, lungs, stomach, and prostate.

“The president’s first hemodialysis was on September 24, 1979. This soon controlled his hypertension,” Aruiza said. “He kept a full schedule, however, interrupted occasionally with emergency dialysis because of pulmonary infections.”

What would eventually finish Marcos off were “his failing kidneys” as he suffered from lupus erythematosus.

Marcos, avid golfer. Photo from The Marcos Revolution: A Progress Report on the New Society of the Philippines (National Media Production Center, 1980).

State secret

Aruiza said Marcos’s true state of health “was the most closely-guarded secret in the Palace.” Cesar Virata, Marcos’s prime minister, confirmed this in a November 23, 2007 interview for the oral history project, “Economic Policymaking and the Philippine Development Experience, 1960-1985” (a.k.a. “The Technocracy Project”):

“(Marcos) did not want us to find out about his health condition. Although we had suspicions because in certain afternoons when we called him by phone, Malacañang would say that he was not available. I think he was having dialysis at those times. He would call back maybe at eight or nine in the evening when the (dialysis) session was finished. It became more frequent, maybe twice a week or something like that.”

Officials who worked in the Palace like Adrian Cristobal, Marcos’s lead speechwriter, claimed they were simply oblivious to the strongman’s condition. Cristobal told James Hamilton-Paterson in America’s Boy (1998): “You may find it hard to believe, but I think I only noticed he was really ill as late as 1984. We were all so busy. Then one day I did notice a patch of fresh blood seeping out on the inner sleeve of his barong. I didn’t know it then, but he’d obviously just come off the dialysis machine.”

Then there were others, like Rafael Salas, who had a strong sense that Marcos was covering up a serious illness and would eventually find a way to confirm his suspicion but shared it only with the people he trusted.

Salas was Marcos’s executive secretary during his first term as president, until they had a falling out and Salas left and worked for the United Nations. Having spent long hours with Marcos, Salas initially believed that “genetically,” Marcos “had a weak intestinal system. He was prone to vomiting and indigestion, which he did his best to hide from everybody.”

In The World of Rafael Salas (1987), he told his biographer, Nick Joaquin, that “there was already something farcical” about Marcos’s health. “He was completely a teetotaler: no alcohol and no coffee or tea. He drank only water and juice. He exercised daily and had as rigid a regimen at table . . . This strict program of diet and exercise did not, however, keep him from falling sick.”

When Salas met Marcos again in 1981, “he was already puffed up from Lupus. He tried to cover up his illness but it was visible to me.”

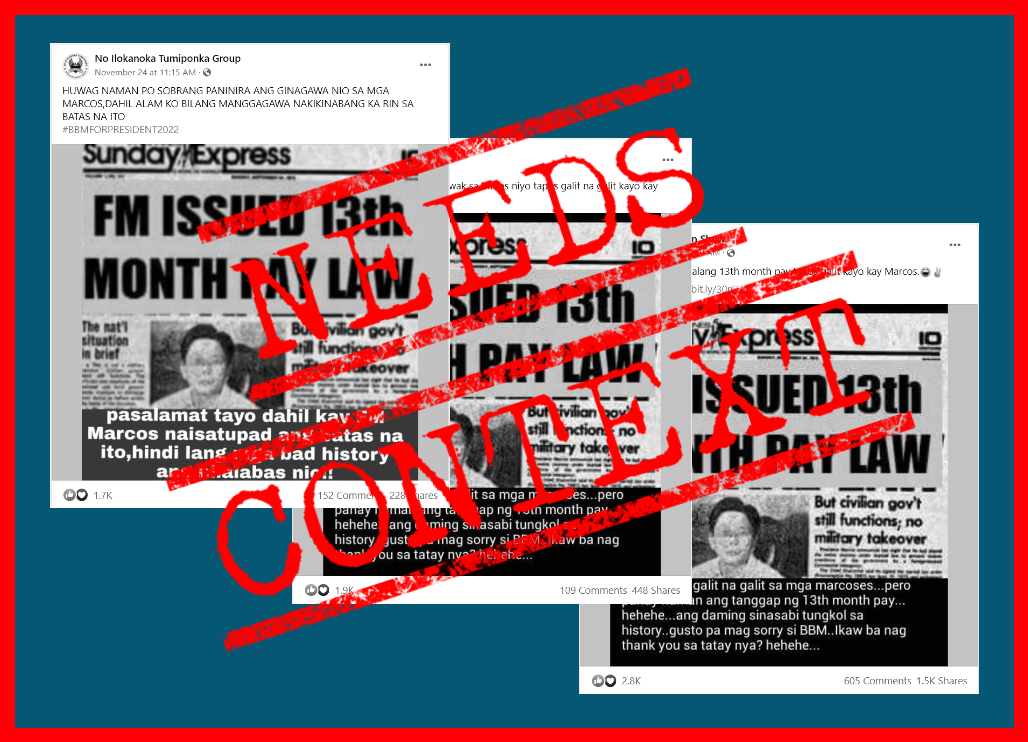

After almost 2 weeks of presidential absence, Senator Christopher Go released this photo on April 11, 2021.

Si Malakas at si Maganda

Then there were those who altogether denied that Marcos was sick.The charade was led by the strongman himself who put to work an entire bureaucracy to boost his image as the Ilocano Leviathan, the Malakas to Imelda Marcos’s Maganda.

“Whenever Marcos was asked about his health, his ready reply was that he was having a ‘bout of flu’ or was just ‘a little bit under the weather’ or his ‘asthma’ was bothering him again. During press conferences, whenever his health came up, his standard jest was to challenge anyone in the room to a few rounds of boxing,” Aruiza recalled.

Several pages of Marcos’s 1964 biography For Every Tear a Victory, which helped propel him to the presidency, explain that his previous ailments—including a supposed tumor detected in 1961 and removed without anesthetics in New York —were linked to injuries and ailments he suffered during the Second World War. The book portrays him as otherwise healthy, and capable of almost miraculous recovery.

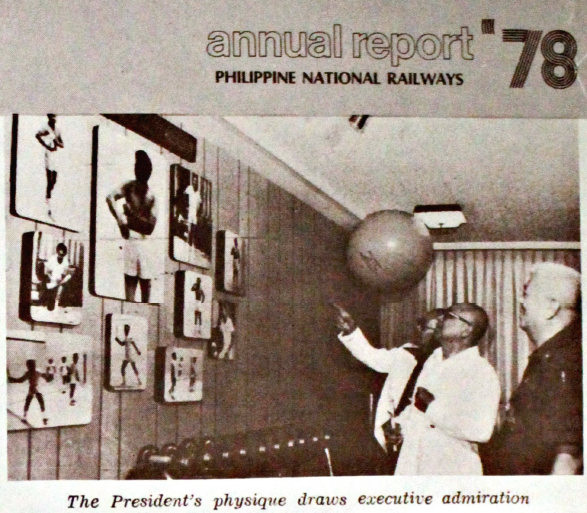

This image of Marcos as an avid golfer and a physical fitness buff was maintained by the Marcos propaganda machine which released shirtless photos of the president displaying a “physique that a man half his age might envy.”

The truth oozed out of cracked walls

But the truth had a way of oozing out of cracks in the wall.

On September 13, 1979, the State Department sent a confidential cable to its embassy in Manila regarding press queries in the United States asking if “Marcos had kidney problems requiring twice-weekly dialysis.”

Two months later, the embassy received another cable informing them of another rumor from anti-Marcos groups in the US: that Marcos was seeking kidney treatment at the Stanford Medical Center. A December 13, 1979 cable followed saying the State Department “welcomes the embassy’s proposed plan to prepare a contingency plan” should Marcos die or be incapacitated since “Marcos’s health is of current concern.”

Burton in her book, Impossible Dream: The Marcoses, the Aquinos, and the Unfinished Revolution (1989), mentions ‘A-1’ information from the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) that Marcos had lupus.

Marcos lasted a full decade after his first dialysis, but the period was marked by the steady decline of his health as evidenced by episodic absences from public view — andludicrous excuses for them offered by Malacañang.

In August 1983, Marcos announced he was taking a three-week vacation, supposedly to finish writing several books — despite persistent rumors that these were actually ghoswritten by the likes of Cristobal.In an article in Ang Pahayagang Malaya a week after the announcement, the First Lady said her husband was just “allergic” to dust particles coming from renovations of their house and was on “self-imposed privacy.”

She described loose talk about Marcos’s failing heath as the “wishful thinking” of his opponents who were “like vultures feeding on rumor.”

“I should be the best barometer of the President’s health, especially since I am quite devoted and intensely in love with my husband,” Imelda insisted.

“The President’s physique draws executive admiration.” From the 1978 Philippine National Railways Annual Report.

Two kidney transplants

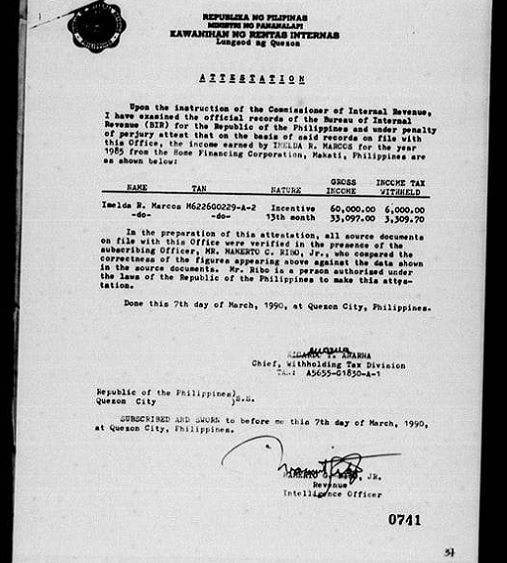

Marcos persisted with the lie. In an interview with foreign correspondents on September 9, 1983, he said, “I can tell you I have not been operated on. I’ve had no dialysis. I have not undergone any unusual operations like strapping myself to a machine, utilizing a mobile dialysis machine.”

In reality, Marcos was feeling the after effects of the first of the two known kidney transplants that he secretly underwent.

Juan Ponce Enrile, Marcos’s minister of defense, wrote in his 2012 memoir that the strongman had a kidney operation on August 7, 1983 citing a Filipino doctor who treated him, and Imelda Marcos in a luncheon at the Palace a week after the surgery. Enrile said he and other visitors were ushered into the guest house and saw Marcos, looking “pale and very weak” from a distance.

Virata learned about the operation two weeks later when he was summoned to Malacañang.In a conversation that followed, Viratas said Marcos admitted that “something went wrong with his system so he had to be operated on,” but concluded that his boss was “misleading us because I think he had a kidney transplant.”

Aruiza said that transplant was the first of two and was performed by a select medical team led by Dr. Claver Ramos at the Philippine Kidney Center. The kidney which, according to Aruiza was donated by Marcos’s only son, Bongbong, was rejected by Marcos’s body and removed 48 hours after the operation.

A second transplant was scheduled on November 26, 1984, with a kidney donated by a “distantly related nephew from the North.” This time, it was successful. Former health secretary Enrique Ona, then a director at the National Kidney and Transplant Institute, confirmed to the media that when Marcos had both operations done by American doctors, the government closed the hospital to the public for three weeks.

When Marcos disappeared from public view again, Imelda tried to dispel the rumors about her husband’s health once more.In an interview with Radyo Veritas she said, “The president is overworked. He is only sick with colds and bronchitis.”

Malacañang then published a photograph of Marcos sitting upright, smiling, and holding up a copy of Bulletin Today with the headline “Marcos stresses he is healthy.”

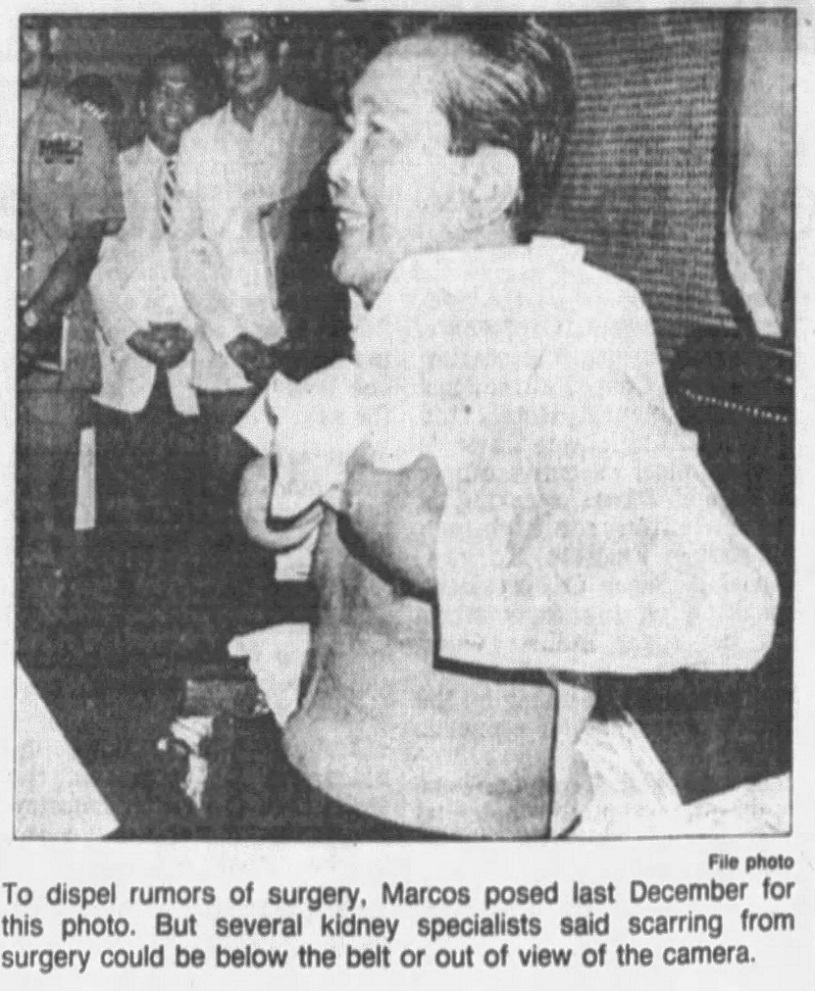

On December 8, 1984, then 67-year old Marcos lifted his shirt in front of his cabinet in a television program aired on a state-run network in an effort to prove that he did not undergo major surgery. Marcos invited photographers to come closer and take shots of his bare, scar-free chest, but foreign newspapers that published the picture carried the caveat from kidney specialists that scarring from a transplant “could be below the belt (area) or out of view of the camera.”

A syndicated photo of Marcos showing his scarless torso; “proof” that he had no kidney transplant. The media made a caveat in the caption.

In his book The Marcos Dynasty (1988), Sterling Seagrave wrote that Marcos ordered his Armed Forces Chief Fabian Ver to find out who leaked confirmation on the second transplant to the CIA and to “silence it.” Media reports linked the death of Dr. Potenciano Baccay on November 2, 1985 to the interview he and Ona did with the Pittsburgh Press on Marcos’ transplants. Baccay was stabbed 19 times while tied with a nylon rope inside his car.

Author Raymond Bonner in Waltzing with a Dictator (1987) offered a clue on how the information was obtained and validated: “A CIA officer succeeded in locating the immigration official at the airport who stamped the passports of two American doctors each time they arrived. With enough money, the agency persuaded the immigration officer to divulge that the doctors were from New York and their names.”

Succession concerns

As Marcos’s bouts with illness became often and severe, people in the military became concerned. Burton would learn later on that then General Fidel Ramos had formed a “crisis committee” that met daily during periods when Marcos got sick “to ensure that the constitution would be followed if something happened to the president.”

“Ramos’s aim,” according to Burton, “was to prevent a takeover by the First Lady, with the help of the Ver faction of the military, and to install in power instead Assembly Speaker Nicanor Yñiguez.”

This was in keeping with the 1973 Constitution which provided that “In case of permanent disability, death, removal from office, or resignation of the President, the Speaker of the National Assembly shall act as President until a successor has been elected for the unexpired portion of the term of the President.”

With the country in severe economic and political crises and the legitimacy of his 20-year rule in question, Marcos called a snap presidential election on February 7, 1986.

Journalists who covered the campaign for the December 19, 1985 poll reported that Marcos had to be carried by his aides from a helicopter to his car, and to the stage.

Marcos admitted to “a little” limp because of an old shrapnel wound from his purported war exploits. His aides, on the other hand, claimed they had to carry the president because so many people wanted to shake his hand. Marcos used the same excuse when a plastic strip was ripped from the back of his hand, causing blood to ooze out.

“In Pangasinan, the people love me (so) very much that they scratched my two hands,” he said.

Eventually, his own body betrayed Marcos. Blood from needle wounds in his arm seeped through his shirt, a urinal became a necessary companion as he fought for his political survival, and on the eve of his exile to Hawaii, as angry Filipinos massed up towards Malacañang, “Mr. Marcos had shitted in his pants.”

A fitting end to his rule, Nick Joaquin wrote in The Quartet of the Tiger Moon (1986). “It seems all too proper that one of the last things Mr. Marcos did in the Palace was to defile it.”

Deja Vu?

And now there is Rodrigo Duterte, who was elected at the age of 71, just a few months younger than Marcos when he died in 1989.

Duterte’s laundry list of ailments and the treatment he uses for them are public knowledge because the president himself talks about them, although varying their severity on different occasions.

During the 2016 presidential campaign, Duterte confessed that he had the typical ailments of people in their 70s, mentioning Buerger’s disease and Barrett’s esophagus. Although he often downplayed the severity of these conditions, Duterte has acknowledged that his Barrett’s esophagus could progress to cancer.

But not once did he offer medical evidence to any of his claims.

In fact, Duterte and his underlings sometimes did not even bother to explain his no-shows and sudden disappearances. When president elect Duterte did not show up for the 2016 Independence Day rites in Davao, the media quoted city administrator (now palace undersecretary) Jesus Melchor Quitain as saying that the mayor was probably still sleeping.

During his April 12, 2021 pre-recorded public address, in response to public criticism about his week-long disappearance, Duterte shrugged off the concern, simply saying, “Sinadya ko yun. Ganun ako e.” By nature like a petulant child, he explained.

Photo of President Duterte on a motorcycle released by Senator Christopher Go while the President was not seen and heard in public first week of April 2021.

In light of the President’s penchant for ghosting and the incoherence of his public addresseses, lawyer Dino De Leon filed a petition before the Supreme Court in April 2020 seeking to force the Chief Executive to release his medical records and citing Section 12, Article VII of the 1987 Constitution.

The provision states that “in case of serious illness of the President, the public shall be informed of the state of his health.” The High Court dismissed the petition outright, ruling that more trust should be placed on the Office of the President to know the “appropriate means” to release information about Duterte’s health.

In issuing the ruling, the Supreme Court cited Blas Ople, a member of the Constitutional Commission that drafted the 1987 charter who introduced the provision. In December 1984, Ople, who was labor minister, was among the first in the Marcos cabinet to publicly acknowledge that the strongman’s health was “undergoing certain vicissitudes.”

It now seems that the health disclosure provision of the 1987 Constitution is difficult to operationalize, with leeway given to the president to determine if his illness is serious. It smacks of a decades-long deceitful game Marcos played with the public. A déjà vu, if you will.

The more forceful legacy of the Marcos regime is the absolute ban on re-election of a sitting president, as contained in Section 4, Article VII of the 1987 Constitution. This and another provision clearly specifying the line of succession in case of “death, permanent disability, removal from office, or resignation” of the president, are among the constitutional safeguards against another Marcos, or an incumbent chief executive holding on to power despite an inability to effectively govern because of illness.

Some may argue that Duterte’s health is not especially concerning, given that he has only a little over a year left in his term. Or that he is indeed quite well for his age and this is just his style of dispensing public office — with utter sloth and habitual distaste for the public he is sworn to serve.

Two things are clear, however: if Duterte is forced to step down due to grave illness, Vice President Leni Robredo – who is from the political opposition – must take over as mandated by the Constitution; and, in this time of a raging pandemic, an absent president fond of keeping the public guessing about his true health condition is the last thing the country needs.

(Joel F. Ariate Jr., Larah Vinda Del Mundo, and Miguel Paolo P. Reyes are researchers of the Third World Studies Center, College of Social Sciences and Philosophy, University of the Philippines Diliman. This piece is part of the Center’s on-going research program, the Marcos Regime Research. The edited transcripts from “Economic Policymaking and the Philippine Development Experience, 1960-1985: An Oral History” have been made available online by the UP Third World Studies Center at http://uptwsc.blogspot.com/p/blog-page_27.html.)