With only a few days left before the May 9, 2022 national election, Leni Robredo and Kiko Pangilinan’s campaign is gaining momentum. Surpassing record after record, the huge turnout of the crowd shows that there is growing groundswell of support for the People’s Campaign.

Indigenous Peoples from different communities all over the Philippines have taken a stand for Robredo and Pangilinan and are playing a central role in the campaign. For indigenous peoples who have long defended their lands, rights, and natural resources, this time is not the time to be silent.

On April 5, Robredo and Pangilinan signed the IP covenant with 1Sambubungan, a coalition of indigenous peoples and IP rights advocates, which embodies their commitment to advance IP rights including the right over ancestral lands. Jennevie Cornelio, a Teduray woman from Maguindanao, said that the event is historical for Indigenous Peoples as it signals the opening of spaces for dialogue, engagement, and participation.

“This is the first time that we became part of the national elections as indigenous women. We were part of the process of drafting the IP electoral agenda. Being part of this covenant and having candidates for the highest positions to listen and committing to stand with us in advancing our rights is a historical milestone. For the first time, we are part of the conversation,” said Cornelio.

Duterte’s killing spree and the shrinking spaces for Indigenous communities

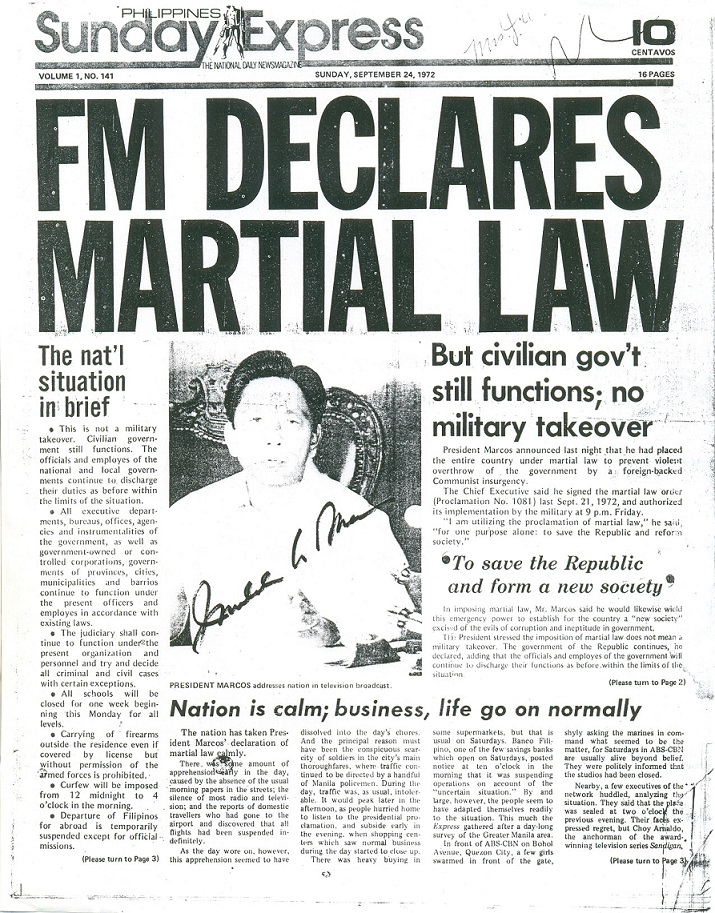

Undeniably, many are taking a stand on the 2022 national election. It is a critical moment for the Philippines. With the son and namesake of late dictator Ferdinand Marcos Sr. topping the poll surveys for the highest position in the land, a sense of impending doom for fundamental rights and freedoms is at stake. A Marcos-Duterte win may spell an end to the country’s democracy and continuity of the bloody legacy of Rodrigo Duterte. But to blame Duterte solely for the current human rights situation and the culture of impunity will be remiss. The road to Duterte was decades in the making.

Case in point is the historical injustice against IPs. The main conflict between the State and the indigenous peoples are the different views on how land, and natural resources are valued. At least 85% of the country’s remaining Key Biodiversity Areas are within ancestral domains. Indigenous peoples are key keepers and protectors of ancestral lands. This speaks volumes of the roles that indigenous peoples, especially women, have embraced and continue to fulfill. On the other hand, the State and corporations look at resources with price tags and not as part of an ecosystem integral to the lives that are dependent on it.

Under martial law, the dictator, Ferdinand Marcos Sr., aided foreign corporations to encroach ancestral lands and ordered the killings of indigenous communities resisting large and destructive corporate projects. Macli-ing Dulag, a village elder from Kalinga, who opposed the World Bank-funded Chico River dam project in Mt. Province and Kalinga was killed by Marcos soldiers. The project would have submerged agricultural lands and sacred grounds of the indigenous communities. Crony capitalism under Marcos decimated over 8 million hectares of forest. Those who profited most were his cronies like Juan Ponce Enrile with his logging concessions, and Antonio Floirendo with his banana plantations.

Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo aggressively allowed mining companies to operate in ancestral domains resulting in violence and displacement. The Kaliwa Dam Project, which was part of the shelved bigger Kaliwa River Watershed projects in the 1970s, is a legacy project that started under the administration of Benigno Aquino III. This project directly threatens the lives and livelihoods of communities within the ancestral domain of the Dumagat-Remontados in Rizal and Quezon. The State and IP relations have for the most part been framed from the lens of counter insurgency. Previous administrations, including Aquino and Duterte have labeled IPs that have resisted government projects, as communists.

The attacks against IP communities intensified under the Duterte government. SANDUGO recorded 92 extrajudicial killings of IPs from 2016-2021 under Duterte. Some of which were executed “tokhang” style. Most of those who were killed were involved in the struggle to defend their ancestral land against encroachments from the government and large corporations wanting to make huge profits from their land and natural resources. The past six years under the Duterte regime and the deeply rooted injustices have been a thorn in the lives and struggles of indigenous women, who have lost their husbands, children, and who themselves are facing risks and danger. Hence, they are in the best position to articulate what is at stake for the May 2022 national elections.

For the indigenous women, this election is a battle for life, dignity, and the defense of the land. A regime change is necessary, because a Marcos-Duterte win will mean the bloodshed among indigenous communities, the killings of their leaders, the red-tagging, and displacement will continue. There will be no space for engagement and dialogue. And the culture of sexism and misogyny will remain unchecked.

Indigenous Peoples Covenant as a space for engagement

The struggle for democratic space is what drives indigenous women to take a stand and invest their time and energy in this campaign. A safe space to exercise their rights and speak freely and critically without fear of being red-tagged, harassed, or killed. Having that safe space means breaking the cycle of violence and impunity from the authoritarian rule established by the Duterte government.

Entering a covenant with Robredo-Pangilinan means indigenous women have decided to make a stand, along with the broader IP movement, and to unite in action to ensure that the next government will recognize them as partners in development, and in forging hope for a more nurturing, and equitable future.

The signing of a covenant is considered a promising start in working together. IPs and advocates will be able to assert a transformation of the State’s framework of engagement anchored on the full realization of indigenous peoples’ rights. Concrete commitments include the investigation and review of the violations of indigenous peoples rights, fast tracking of the approval of applications and release of Certificate of Ancestral Domains Titles (CADTs), and the enactment of Peoples Mining Bill or the Alternative Minerals Management Bill (AMMB) to replace the flawed Philippine Mining Act of 1995.

While the covenant is a welcome development in IP communities and amongst advocates, “space”, is first and foremost, sought for by everyone. With many voices and diverging views in the larger political spectrum, and even in broader social movements, women’s movements, and various sectors, space is limited; and a safe space for indigenous women is even more scarce. Hence, sustaining the energy and participation of IPs, particularly indigenous women, is crucial.

Making Herstory

Indigenous women have been invisible to politicians except perhaps during the election period. They have recounted their experience of being loaded into trucks paid for by local politicians to register in COMELEC. Come election time, they spoke about being transported to polling precincts to cast their votes in favor of certain politicians. Election-related violence is rampant as well and has resulted in displacement, harassment, and killings. This cycle of traditional politics and how the rotten political system operates have shaped how indigenous women view elections as a circus that only benefits the few and further marginalizes their communities.

What has changed now for the indigenous women is the invigorating energy and spirit to be part of the Peoples’ Campaign. They have participated in different electoral discussions, among themselves, and with broader movements. They were also part of the women’s covenant with Robredo-Pangilinan, which included the genuine process of Free, Prior, Informed Consent (FPIC) ensuring meaningful participation of indigenous women, as well as in other policies and program development. The women’s covenant also includes the reiteration of support for non-discriminatory and safe indigenous practices of women; seeking an end to violence against indigenous communities such as the criminalization of indigenous practices (e.g, home birth-giving); and the provision of adequate support to ensure that indigenous practices are safe and respectful of women and girls’ human rights.

This is indeed HERstorical as indigenous women are actively taking part in the movements involved in the electoral campaign, pushing for their agenda to be part of the main discourse. They may have meager resources, but they are running high on volunteerism. Conducting house-to-house, community dialogues in the smallest sitios, in the mountains, and across rivers. Some of them have conducted rituals to seek guidance and protection for the Leni-Kiko tandem, and for the sole indigenous senatorial candidate, Teddy Baguilat.

In this campaign, indigenous women are breaking barriers against the recognition of their own leadership within their communities because some traditional male leaders are still the decision-makers, and some communities still vote as “one tribe, one vote.” Indigenous women are challenging the notion that women cannot and should not lead by arguing that Leni, a woman, has a good track record and the competence to become our president. In this campaign, the indigenous women have found their voice and have made up their minds – they are voting pink.

This election is sweat and blood for indigenous women, and their communities. Should a People’s Campaign propel Robredo-Pangilinan to win the 2022 election, the energy and spirit of indigenous women must be sustained to assert the promise of Gobyernong Tapat, Angat Buhay Lahat (Honest Government, a Better Life for All).

*Judy Pasimio is the Overall Coordinator of LILAK Purple Action for Indigenous Women’s Rights. She also became the Executive Director of Legal Rights and Natural Resources Center (LRC-KsK/Friends of the Earth Phils), whose main partners were indigenous peoples, struggling for their right to self-determination.

Jayneca Reyes, is the Communications Focal Person of LILAK and a lecturer in Far Eastern University, Department of Communication.

The views in this column are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of VERA Files.