Journalist Philip Lustre Jr. has reposted his version of the last day of the late Ferdinand Marcos Sr. in Malacañang (Feb. 25, 1986), written two years ago, to counter the version of Sen. Imee Marcos that will be shown in the movie “Maid in Malacañang” about the last three days of the Marcos family in the president’s official residence.

I’m re-reading the book “Ferdinand E. Marcos, Malacañang to Makiki” by Col. Arturo C. Aruiza, who served as aide-de-camp and confidant of the late president for 21 years until the latter’s death in Honolulu, Hawaii in 1989.

Described as the “Last Loyalist,” Aruiza passed away in 1998 in Las Vegas at the age of 56.

I’m sharing here excerpts from Aruiza’s intimate, gripping account of the scene in Malacañang on the evening of Feb. 25, 1986, such as the boxes of money in Marcos’ bedroom and the gravely ill president not remembering the combination lock of the steel safe box where important items were kept.

From Chapter 5, Defections:

“By then, the confusion and anxiety in the Palace was unbearable and, any moment, sheer panic would overcome us. I decided to tell the president myself. I had never before entered his bedroom alone. In the past, when I saw his bedroom, that most private of rooms, where Ferdinand E. Marcos shed his guard and enjoyed the brief luxury of being human like us, sleeping, reading, washing up, watching TV, it was to follow him into it, to deposit his load of papers, documents, or attaché case.

“This time, I knocked alone on the heavy wooden door twice and pushed it, and saw what I feared to see.

“He was lying in a hospital bed that was pushed to the right side of his spacious room. His eyes were closed. Surrounding him, perched on chairs or tiptoeing around, were his doctors, the unflagging, faithful two, Dr. Juanita Zagala and Dr. Claver Ramos; the nurses, Betty A. Bondoc, Evelyn Baylen, Fe C. Antonio; the attendants, Hermina Ranada and Minerva Corpus. A handful of security agents and valets stood guard on one side. These were Restituto Alipio, Ferdinand Bolibol, and Benjamin Sarmiento.

“Mattresses littered the floor. The grandchildren had slept in them, also in the modest presidential bed, which was unmade. Hundreds of books were piled everywhere in the room, and on his table were stacked papers and documents.

“Those in the room looked up hopefully when they saw me, as though asking what was happening outside. I had no good news to bring them. As I took the disorder in the room and the sleeping form in the bed, I imagined the rebel soldiers and the mob at their disposal, rushing in.

“I motioned to Dr. Zagala and asked to talk with the president. This lady doctor would serve him steadfastly, following him into exile, standing beside him through the harrowing days of coma and delirium, not leaving him until he died, told me that Marcos was feverish, 39°C.

“The president must have heard us murmuring because he opened his eyes. Dr. Zagala told him I was there. Quickly I explained the situation outside. If the mob got in, if the rebel soldiers got in, we would fight, and there would be carnage. Painfully he struggled up, helped by his nurses. On his feet at last, he ordered his security, Alex Ganut Jr., Jovencio Luga, and Ben Sarmiento to pack his clothes, his books and papers, and then told me to call up Enrile from his bedroom.

“At this, the two doctors asked the nurses to put all his medicines in bags and boxes. Dr. Claver Ramos (not related to Fidel Ramos) gathered the president’s medical records and then asked someone to look after the medical equipment.

“I handed the phone, with Enrile on line, to the president, who asked Enrile if the men who had beaten up and then stabbled Ernesto Manuel and also beaten up the rest of Manuel’s men had been Enrile’s people. Where I stood beside Marcos, I deduced that Enrile was still calling him, ‘Sir.’

“‘No,’ Enrile said to Marcos, no, they were not his men, but he would ask ‘Fidel’ to investigate.

“That was their last conversation: there were more pauses than dialogue. I waited for Marcos or Enrile at the other end to say a word or two to show that something of their 20 years together still remained. I wanted for the president to say, ‘Good luck, Johnny!’ and for Enrile to say, ‘I’m sorry, Mr. President,’ but there was just this long silence followed by the sound of the telephone being put down.

Chapter 6, Kidnapped:

“After talking to Enrile, the president told his other son-in-law, Tommy Manotoc, to call up his friend at the US Embassy and accept the offer of transportation out of the Palace. Everyone now took this to mean we were leaving at last. We all began to pack, not only the president’s clothes, books and papers, but also the boxes of money that had been stored since the campaign in his bedroom.

“The First Lady’s attendants started to put her things together, too. The three agents manning the telephone booth had unhooked their phones to help Fe Roa Gimenez. “The traffic between the bedroom upstairs and Heroes Hall below grew more frenzied as all kinds of luggage made their way down. There were carton boxes, garment bags, duffel bags, travelling bags, leather bags, attaché cases, Louis Vuitton bags, suitcases and just plain boxes packed but their flaps left unsealed.

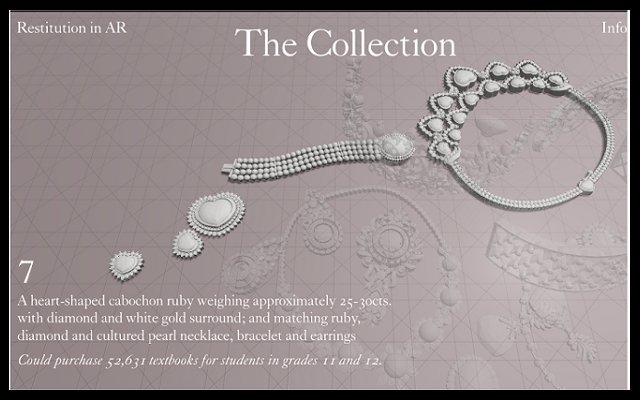

“We ran into a serious problem when we could not open Marcos’s steel safe in his bedroom. Fatigue, medication, and lack of sleep had blotted out the combination from his memory and we had no way getting its contents. These included important papers and documents, a priceless gun collection, expensive gifts like watches he never wore since he preferred his old Omega silver watch.

“In particular, there were two rare watches, probably adorning some strangers’ wrists now: a Patek Philippe gold watch and a made-to-order Rolex watch with the maps of the Philippines and Sabah on its face.

“Now, he could not remember the combination to the steel safe and there was nothing we could do. This was the man who could recall dates at the drop of a hat. The numbers of the presidential decrees. Names of friends not seen in 30 to 40 years. Conversations let off decades ago. Hundreds of articles in law books. And now, just a couple of numbers had slipped his exhausted mind and we were helpless.

“He decided not to waste time over the safe’s combination. Instead he picked up a brown Samsonite attaché case, gave it to a valet and told him, under pain of his displeasure, not to open it or part with it.

“The odd part is that he did not seem to care that he could not remember. Earlier in the day, hearing that Mrs. Aquino had taken her oath ahead of him, he had shown no emotion. Now the stubborn safe stared back at us and the president reacted similarly with uncharacteristic indifference as though leaving it all to us, together with the unopened safe, leaving his life and his fate to us.

“Four years later, however, there would be an interesting sequel to that unopened safe.”

(To be continued. In my next column, we will find out what happened to the safe and the attaché case that Marcos entrusted to his valet. Aruiza also narrated about boxes of Imelda Marcos’ jewelry and the packing that Imelda Marcos did.

(Notes: Ernesto Manuel, a former cadet of the Philippine Military Academy who was a Marcos loyalist.He and fellow Marcos loyalists were on their way to Channel 13 to bring the tapes of Marcos’ oathtaking when they met Cory Aquino supporters, who pounced on them.

(Fe Roa Gimenez was Imelda Marcos’ private secretary.)

The views in this column are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of VERA Files.