Barangay chairperson Edwin “Toto” Ganan of Barangay 29, Pasay City was killed on August 10, 2016 while he was in police custody.

Like many similar deaths, the official report said Ganan grabbed the gun from the police, prompting them to respond and shoot him in the face and chest.

Ganan’s live-in partner, Nini Crisologo belies the police’s claim. She said Ganan, who was in the law enforcers’ drug list, was in handcuffs when he boarded the police vehicle. Crisologo said her partner was a victim of the “palit-ulo” scheme.

Palit-ulo literally means head swap. Talked about in hushed conversations, it’s a notorious police practice of detaining a suspect’s close relative until such time the latter surrenders. Human rights lawyers condemn the illegal scheme.

The PNP admits that the practice exists but not in the way common people imagine it. For the police, palit-ulo means the filing of a lighter charge against an arrested suspect, provided the suspect gives damaging information on others who may have greater involvement in the criminal enterprise.

Crisologo alleged that it was Victor del Mundo, also a resident of Barangay 29, whom police earlier identified as a drug suspect. She said when del Mundo was questioned by the police, he turned informant, ratting on Ganan to gain freedom.

Another village chief, William Abundo of Barangay 168 in Pasay City, was killed on September 26, 2016 in a billiard hall by two gunmen on a motorcycle. The police reportedly said Abundo was involved in illegal drugs. However, his friend attested that Abundo was killed because he refused to submit a list of drug suspects in his barangay.

Ganan and Abundo were among 85 former or current barangay officials killed from July 1, 2016 to October 31, 2020.

Last November 5, the Philippine Drug Enforcement Agency released to the public their most recent figures on the government’s war on drugs covering the period July 1, 2016 to September 30, 2020. PDEA’s Real Numbers peg the drug war deaths for the said period at 5,903. The data includes a tally of government workers arrested in anti-drug operations: 438 government employees, 356 elected officials, and 102 uniformed personnel.

PDEA fails to mention that government workers, barangay officials in particular, were also getting killed in the administration’s anti-drug campaign as shown by the project “Violence, Human Rights, and Democracy in the Philippines.” The joint project of the UP Third World Studies Center and the Department of Conflict and Development Studies of Ghent University found that at least 85 former or current barangay officials have been killed from July 1, 2016 to October 31, 2020.

More perilous time for barangay officials

Barangay officials may be in for a more perilous time.

On September 25, 2020 PDEA Director General Wilkins Villanueva said, “Dapat magkaroon ng Barangay Anti-Drug Abuse Council (BADAC), if they don’t have in their barangay, then si kapitan, totokhangin na natin.” Villanueva added that they will start “tokhang” operations against said barangay captains once the Covid-19 pandemic is over.

But Villanueva clarified that the “tokhang” operations will follow the “knock and plead” technique and not the bloody drug operations that were carried out in Metro Manila and elsewhere. This shift in tone, if not in approach, may have been too late.

Data released recently by PDEA showed of the 42,045 barangays in the country, 20,289 or 48 percent are said to be cleared of illegal drugs. The number of barangays “yet to be cleared,” is at 14,091 or 33 percent of the total number of barangays. PDEA made no mention of the 7,665 barangays that are in neither category.

Officials of these barangays, specifically those without a functioning BADAC, could face tokhang as PDEA warned that failure to abide by the Department of Interior and Local Government directives in creating such a council could be an implication of negligence and could raise suspicions of law enforcement agencies.

This barangay-based council is used by the PDEA, the Philippine National Police, and DILG to closely monitor illegal drug activities in each locality as well as to implement localized drug rehabilitation projects. For Villanueva, anti-drug operations must be conducted at the barangay level because illegal drugs always make their way to local communities no matter where they came from.

Hence, because these local councils do not exempt barangay officials from surveillance, they were already facing threats from Oplan Tokhang since its nationwide implementation in 2016.

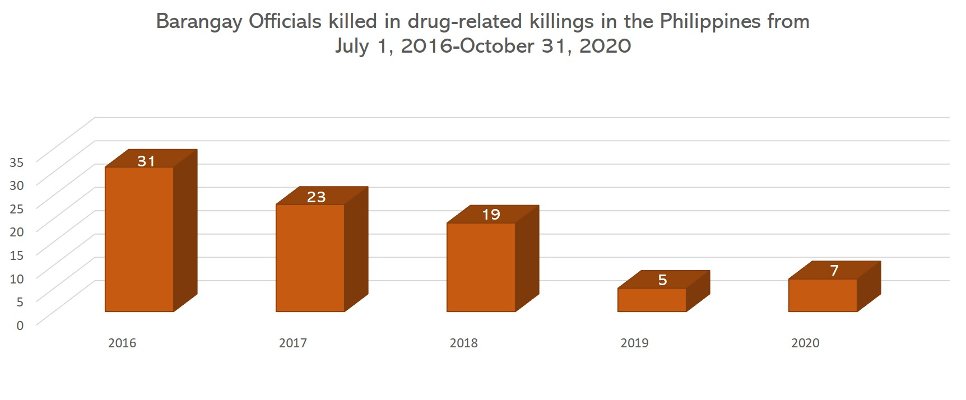

Figure 1. Number of victims of drug-related killings who were reported to be barangay officials in the Philippines from July 1, 2016 to October 31, 2020.

The Critical Role of Barangay Officials in the Anti-drug Campaign

Barangays (villages) are the smallest political unit in the country with at least 2,000 inhabitants each for those in rural areas and 5,000 residents for barangays in highly urbanized cities. Like other levels of local government, barangays have a set of elected officials namely one chairman, seven councilors and a Sangguniang Kabataan (youth council) chairperson. Together with other barangay officials such security officers and watchmen, they carry out their dual role in delivering local public services and implementing national policies—the drug war of which, since President Duterte took office, is given utmost priority.

While the drug war is centered on the police, barangay officials play a key role prior to actual law enforcement operations and in the implementation of the campaign, because of their proximity to the people in their communities. Their knowledge of, and influence in their communities are seen as an opportunity for law enforcers to closely monitor the prevalence of drugs in their localities.

Sen. Ronald “Bato” Dela Rosa, in Reuters’s “Special Report: In Duterte’s War on Drugs, Local Residents Help Draw Up Hit Lists” on October 8, 2016, said barangay officials “are on the forefront of this fight” and that “they can identify the drug users and pushers in their barangays. They know everyone.”

The strategy to combat the drug problem by going straight to the barangays dates back to the 1998 mandate to create the Barangay Anti-Drug Abuse Council. At first, BADACs were barely functional. In an August 26, 2016 report by Rappler, two months into the Duterte administration, Dangerous Drugs Board Undersecretary Rommel Garcia reasoned that this was because the existing memorandum circular on the creation of the BADACs did not require LGUs to allocate a specific amount for its operation. Enter President Duterte’s vehement stance against illegal drugs. The DILG and the DDB in 2017 issued memorandum orders for every barangay in the country to mobilize their BADACs in the drug war.

Weaponizing BADACs in the drug war comes with a DILG surveillance program called MASA-MASID or Mamamayang Ayaw sa Anomalya, Mamamayang Ayaw sa Iligal na Droga (Citizens Against Anomalies/Corruption, Citizens Against Illegal Drugs). This program encourages citizens to inform on others who may be involved in illegal drugs as well as other criminal activities, including terrorism.

A study by Mong Palatino titled “Tokhang in North Caloocan: Weaponizing Local Governance, Social Disarticulation, and Community Resistance” published in Kasarinlan: Philippine Journal of Third World Studies, argued that these memos cemented the critical role of barangays in the campaign. The barangays and the BADACs were tasked, among others, to come up with a list of suspected drug personalities to be submitted to the PNP; to evaluate who among the voluntary surrenderees are qualified for rehabilitation; and to participate in actual operations such as inspecting drug dens, tagging along actual police operations, and even arresting drug dealers and users. Barangays that fail to comply with the guidelines set by the DILG were warned of administrative and criminal charges.

Despite these strict guidelines and the threat of charges, barangay officials have been shown to exercise some level of discretion when implementing these roles. In a piece by the Philippine Center for Investigative Journalism published on May 16, 2018 titled “Barangay Officials Make Tough Choices in the Drug War,” other than willful submission to the inevitability of killings, some barangay officials looked for ways to avoid adding to the body count.

One of the officials featured in the report warns his constituents they will be part of a list of suspected drug personalities to be submitted to the police. He ensures that targeted drug suspects will be either jailed or asked to leave the province so as to save them from the possibility of an impending death at the hands of police. Another official, a widow of a barangay chairman shot by masked vigilantes, felt hopeless about stopping the killings. She instead focused her efforts in addressing what she thought as the root of why people take the path of drugs and crime. By doing so, she hopes to lessen the number of killings by reducing would-be criminals.

Barangay Officials as Victims of Drug-related Killings

Yet, barangay officials, whether they exercise utmost compliance or subtle defiance, still stand on precarious grounds. Being at the forefront of this campaign, compliance leaves them vulnerable to assailants associated with the drug trade. On the other hand, not fully complying with directives subjects them to the government’s hasty conclusions that equate non-compliance with support to the illegal drug trade. This puts them at the same risk as suspected drug pushers, where mere suspicion becomes the basis for the police or emboldened vigilantes to take away their lives.

In data from July 1, 2016 to October 31, 2020 that we gathered, 85 of the total 3,368 drug-related deaths recorded were of either former or current barangay officials from different parts of the country. This number was out of the 18.41percent or 620 of the victims who had their occupations included in the reports. The occupation of 81.59 percent or 2,748 other victims were not reported.

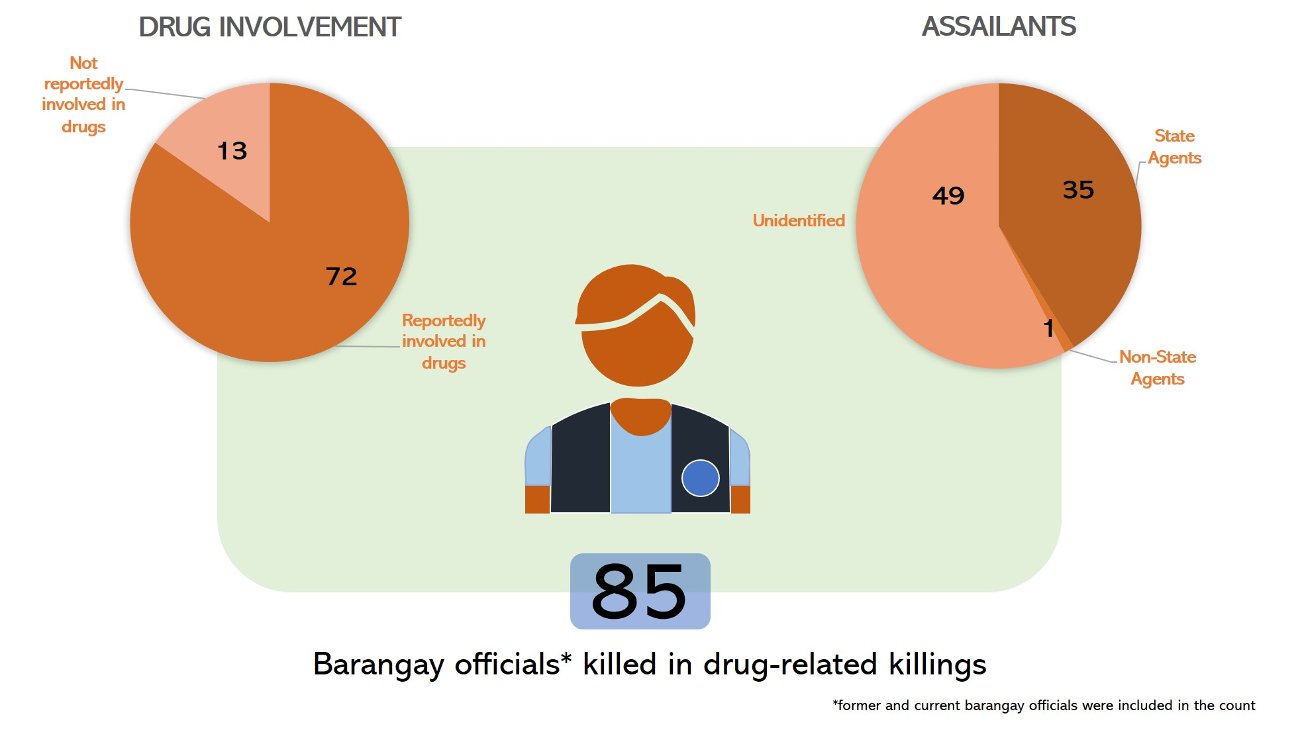

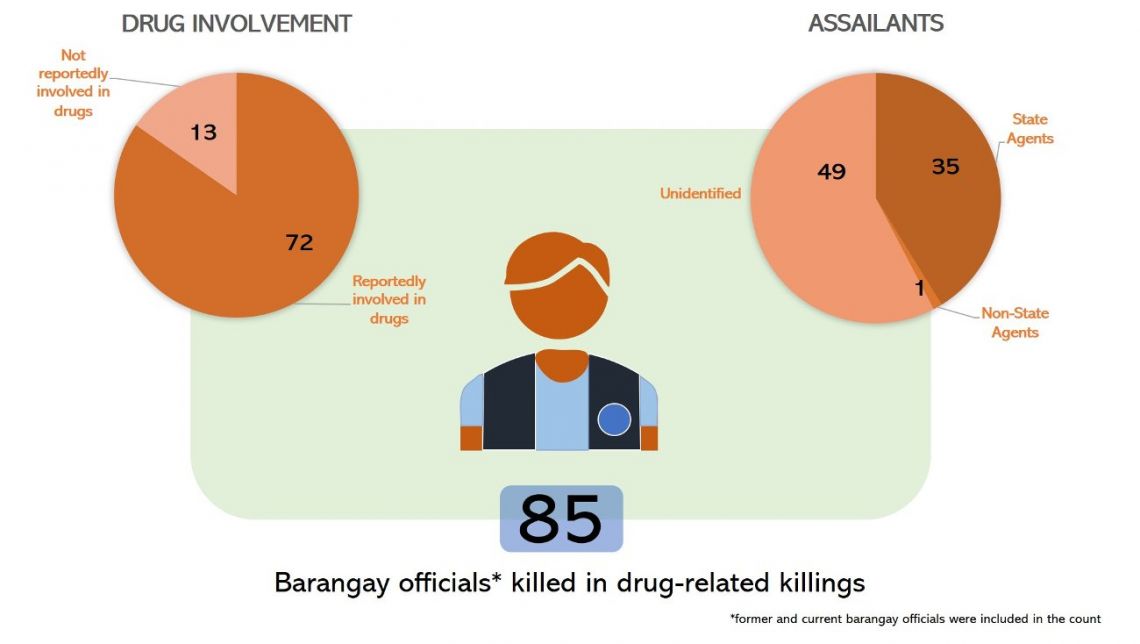

Of these 85 barangay officials, 72 were said to be involved in drugs. Twenty-four of them were allegedly included in a drug watchlist.

Figure 2. Barangay officials killed in drug-related killings with information on drug involvement and their assailants from July 1, 2016 to October 31, 2020.

One of them was a barangay chairperson of Talomo, Davao City. The report stated that Artemio Jimenez Jr., allegedly included in the city’s drug watchlist, was killed by unidentified gunmen on September 16, 2016. Prior to his death, Jimenez reportedly tried to clear his name by proving that he tested negative for drugs.

In a more recent incident, on October 20, 2020, two former barangay officials were killed in separate drug operations in South Cotabato and Davao del Sur. Diosdado Cruz, former chairperson of barangay Rubber in Polomolok, South Cotabato, was killed by the police after an alleged shootout. Cruz was reportedly a member of a local terror group Dawlah Islamiyah and was previously arrested over drug charges on March 28, 2019 but was released on April 2, 2019. Another shootout in Davao del Sur left dead a former barangay councilor of Dulangan, Digos City. Roy Miro Calingacion was an alleged high-profile target and was previously arrested for drug-trafficking in 2011 but was released from jail in 2019.

Fourteen of the barangay officials killed reportedly either operated a large-scale drug trade or condoned such activities within their localities. Two of them were killed by unidentified assailants while the remaining twelve died in police anti-illegal drug operations.

The other 13 barangay officials killed within the context of the war on drugs were reportedly not involved in the illegal drug trade. One of them was killed by an identified attacker while the remaining 12 were killed by unidentified assailants.

Wilson Batucan, a barangay watchman in Barangay Cansaga, Consolacion, Cebu, was killed by unidentified assailants on March 28, 2017, three months after his seven-year-old son was killed by a stray bullet fired by masked men chasing a drug suspect in their barangay. Batucan was active in seeking justice for the death of his son as he reportedly told his wife that the masked men responsible for their child’s death were policemen. However, Batucan gave no names to his wife to prevent her from getting involved in the issue. He also reportedly refused a financial offer in exchange for not pursuing the investigation on his son’s death. Contrary to these, the provincial police director of Cebu claimed Batucan was likely killed by the drug suspect eluding an arrest in which the barangay watchman took part.

It is hard to get off the list even for barangay officials promising to better themselves. Ignacio Gallero, a village watchman, partner to Jerlyn Bernal and a father of four, was shot by one of six unknown men who surrounded his house on February 22, 2017. He was previously suspended for testing positive for illegal drug use. He was reinstated after vowing to change for the better. Gallero reportedly participated in rehabilitation programs and activities. He remained, however, in the watchlist. The night he was killed, Jerlyn pleaded with the killer not to shoot Gallero.

Unidentified assailants killing people suspected of links to the drug trade is not something unique to barangay officials. What is striking in our data, however, were barangay officials getting killed by unknown assailants for their support of the drug war.

Our report in Vera Files, “No Let-up in ‘Tokhang’ Even During Quarantine,” mentioned Melody Quijano, 39, a barangay councilor in De La Paz, Biñan, Laguna, She was killed on her way home by motorcycle-riding gunmen. She just finished her shift in a checkpoint during the lockdown in April. As a barangay councilor, she was said to be an active supporter of the campaign against illegal drugs.

Bernardo M. Lerio, a barangay chairman in Sorsogon, was similarly reported to have been an active supporter of the government’s anti-drug campaign. He was shot to death by motorcycle-riding gunmen on June 14, 2017. In another case, a former barangay councilor described by police as an active supporter of the anti-drug campaign was shot multiple times by an unidentified man.

The drug war has put barangay officials in a very tight spot where a single misstep could mean finding themselves at gunpoint. Whether active in the fight against illegal drugs in their localities, or holding reservations with the way the government chose to handle the problem, barangay officials still face imminent threats either from unidentified assailants or from law enforcement agents. Without any let-up in tokhang operations amidst a pandemic, nor in killings even without threats of tokhang from higher authorities, barangay officials continue to add to the number of drug-related deaths.

Jamaica Jian G. Gacoscosim and Nixcharl C. Noriega are research associates at the Third World Studies Center, College of Social Sciences and Philosophy, University of the Philippines Diliman. This piece is part of the on-going research project, “Violence, Human Rights, and Democracy in the Philippines.” The project’s output can be accessed at dahas.upd.edu.ph. Joel F. Ariate Jr. provided additional research.