By MA. NIÑA PAMELA CASTRO and BRYAN EZRA GONZALES

OFTEN disenfranchised for reasons ranging from violence to illiteracy, indigenous people (IP) voters last week were given a peek into what hopefully could be more inclusive elections in the future.

In Oriental and Occidental Mindoro during the May 9 polls, a pilot initiative to bring polling places closer to Mangyan communities was received “overwhelmingly” by them.

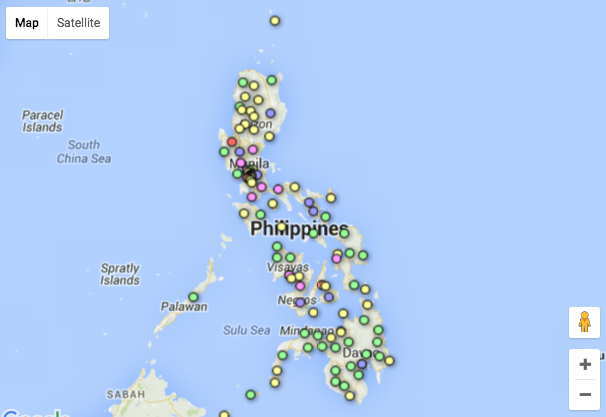

While voting problems persist in other IP communities elsewhere, stakeholders hope the Mindoro project could be replicated across the country in the coming elections.

“The Separate Polling Places (SPPs) and the Accessible Voting Centers (AVCs) put an end to the long lines of IP voters in the regular polling places where Mangyans used to vote,” said lawyer Erwin Caliba of the National Commission on Indigenous Peoples (NCIP).

SPPs are additional polling places established in existing voting centers where qualified IP voters can cast their votes. AVCs, meanwhile, are newly established voting centers located closer to the communities of registered IP voters.

They were organized in line with Comelec Resolution No. 10080, which ordered the installment of SPPs and AVCs in pilot areas around the two Mindoro provinces to address access, discrimination, and “hakot” or hamletting issues.

“The SPP and AVC were a great voting experience for Mangyans,” said Caliba, citing interview reports conducted by monitors from the NCIP, as well as the Commission on Human Rights (CHR), the Legal Network for Truthful Elections (LENTE), and the Commission on Elections (Comelec) itself.

“When asked if they want to be voting in (these special polling places), Mangyan voters overwhelmingly answered in the affirmative,” Caliba said.

“We hope for the replication of the project in all areas where there are IPs in the succeeding electoral exercises,” he added.

Comelec had set up 23 pilot voting centers in the two Mindoro provinces: 14 SPPs and two AVCs for Oriental Mindoro; and four SPPs and three AVCs in Occidental Mindoro.

Both provinces have a total IP population of 20,274, 14% of whom are qualified to vote.

In a statement, Comelec spokesperson James Jimenez reported Saturday that in 16 of the 23 centers, 2,587 of the 2,878 Mangyan voters participated in the elections, which translates to a 90 percent voter turnout rate.

Jimenez described the IP voting initiative as “successfully conducted.”

Rich Apollo Mamhot, administrative officer at LENTE, said the towns of Rizal and Calintaan in Occidental Mindoro did not participate in the project because election reform groups failed to secure the consent of the Mangyan communities there.

Mangyan voters who declined to participate in the pilot IP polls voted instead in regular polling places in existing voting centers, he said.

“Isa ito sa mga pangarap ng mga katutubo. Di sila nakakaranas ng diskriminasyon (This has been one of the dreams of IP voters. They did not experience discrimination in SPPs and AVCs),” Mamhot said.

From the hinterlands to the ballot box

Discrimination, the long travel time from the hinterlands to the ballot box, and being hamletted for their votes by local politicians are major challenges confronting IP voters, which SPPs and AVCs seek to address.

In previous elections, Mangyan voters from far-flung areas in Mindoro would take up to three days to walk to the nearest polling place.

Finally reaching their destination, some are forced to step aside and wait for other to finish casting their ballots, said Pastor Lando Sama of the Mangyan Tribal Churches Association.

“Inuuna yung mga nakapag-aral, may-kaya at Tagalog. Kaya maraming Mangyan ang di nakakaboto (Voters who are educated, rich, and Tagalog are given preference. That is why many Mangyan voters had been unable to vote),” Sama said.

Voters from the lowlands were sometimes alarmed by the unpleasant odor IPs incurred from their long journey, he added.

Politicians would also round IP voters up and provide them food and shelter before sending them off to cast their ballots in their respective voting centers, a practice commonly known as “hakot.”

At times, Sama said, local officials would keep the IP voters in a remote safe house for a prolonged period of time if they felt that the IPs would not vote in their favor.

“Haharangan at kokontrolin ng mga kandidato ang mga botante (Candidates prevent IPs from voting),” Sama said.

The pilot IP voting in the Mindoro provinces sought to remedy these, either by having a polling place that catered solely to IPs, or else bringing the polling place right at the doorstep of their communities.

Said Mamhot of LENTE, travel time for some IPs was reduced to just one to two hours.

Problems persist

Yet, despite SPPs and AVCs, cases of “hakot” or the practice of hamletting IP voters had still been observed in the two Mindoro provinces.

An incumbent official from Paluan, Occidental Mindoro was reported to have threatened several IP voters for refusing to transfer from the AVC at the Katuray Elementary School to the regular voting center in the municipality, according to a complaint filed by LENTE observers in the area.

In the same town, poll watchdogs said around 100 Mangyan voters were offered transportation to their precincts and given cheat sheets.

In San Teodoro, Oriental Mindoro, a local candidate was found sponsoring trucks for several IP voters.

Despite these cases, LENTE said the pilot IP voting was able to reduce such incidents compared to previous polls.

Elsewhere, meanwhile, IP voters continued to grapple with the difficulties of voting without SPPs and AVCs.

In Norzagaray in Bulacan, Freddie Repoverbio, a registered Dumagat voter, said many IP voters needed to bear with hours of boat rides and hiking to get to their precincts.

Repoverbio said this has forced Dumagat voters to rely on transportation services sponsored by local officials.

“Sabi nga nila, ikaw ay isang mamamayan, responsibilidad mong bumoto (As a citizen, it is one’s responsibility to vote)”, Repoverbio said. “Yun nga lang ang pakinabang namin sa gobyerno (In the eyes of the government, we are only worth our ballots).”

At the United Church of Christ in the Philippines Haran compound in Davao City, registered Lumad voters seeking refuge were not able to cast their ballots due to death threats posed by the Alamara, a paramilitary group allegedly recruited by the military stationed in Southern Mindanao.

Datu Mentroso Malibato of the Lumad rights organization Karadyawan To Tibo Tribu (For the Welfare of All Tribes) said members of the Alamara threatened to burn the evacuation site and kill the Lumad leaders inside the compound because they refused to return to their communities in Davao del Norte.

Malibato has been staying at the Haran evacuation site for more than a year now, along with 700 Lumad evacuees displaced by ongoing conflicts between government forces and the New People’s Army (NPA) in the Davao region.

“Pag nakita nila kami, patay kami (If they see us, we are dead),” he said.

Something to start with

Such problems highlight the need for more continuing efforts to ensure that IP voters in coming elections get to exercise their right to suffrage.

For now, stakeholders bask in the success of the Mindoro initiative, and hope to build on it and other previous efforts promoting inclusive elections for IPs.

Some of these had already been implemented in previous elections, as in 2012, the year before the midterm polls, when Comelec, NCIP and the Department of Interior and Local Government (DILG) jointly agreed to address the logistical concerns, research, and information dissemination of IP voter registration.

That year, registration drives and voter education programs were launched for the Tedurays in South Upi, Maguindanao; the Kalanguya, Iwak, Ibaloi, Kankanaey, Karao, Tuwali, Ayangan, Isinay, Hanglulo, Subanen, Itneg and Kalahan in Kapayapa, Nueva Vizcaya; the Kankanaeys in Ilocos Sur; and other IP groups in Capas, Tarlac, Nakar, Quezon, Buhi, Camarines Sur, Valderrama, Antique; Malita, Davao Occidental, Lake Sebu, South Cotabato, and Bakun, Benguet.

Say stakeholders, the successful IP voting project in Oriental and Occidental Mindoro is a sign of hopeful things to come.

There have been constraints in the execution of the IP voting initiative, said CHR chair Jose Luis Martin Gascon, but the pilot test has generated awareness on the challenges confronting IPs and other vulnerable sectors during elections.

“In the past, there was no attention given to the vulnerable groups,” Gascon said. “But now, there are special initiatives and efforts (for these sectors).”

Gascon said the commission has yet to collate reports from monitoring teams deployed in several indigenous communities during the elections.

Caliba of NCIP said he hopes the initiative would benefit more IP communities in future elections.

“At least now, we have something we can start with,” Caliba said.