Residents and officials explore solutions beyond temporary closures

GUINOBATAN, Albay—Super Typhoon Uwan sent floodwaters racing through Barangay Masarawag, a riverbank community in this town long shaped by shifting rivers, erosion and quarrying at the foot of Mayon Volcano.

But residents say 2025 feels different.

Floods now arrive without warning, even on days that begin bright and calm. “It’s sunny in the morning, yet in the afternoon we’re flooded,” Barangay Councilor Judith Pabelona told BicoldotPH. This year’s repeated floods and lahar surges have forced several evacuations and deepened emotional strain.

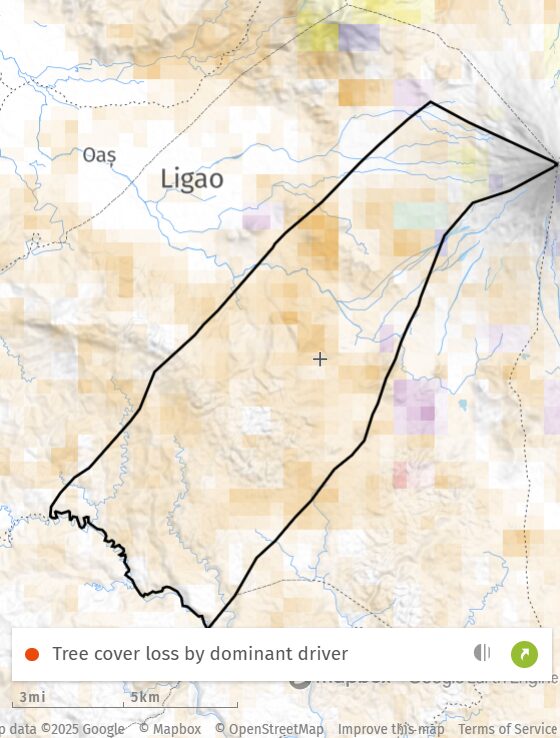

Municipal Disaster Risk and Reduction Management Office (MDRRMO) officer-in-charge Joy Maravillas said Masarawag sits along old river channels where land-use changes altered runoff paths. Quarrying is no longer active in the barangay, but nearby sites such as Maninila in Guinobatan and Budiao Channel in Daraga were recently shut down after being deemed “critically hollowed out.”

Across Albay’s second district, 35 quarry operators have been suspended or had permits revoked for over-extraction. “Our goal is to protect critical areas and prevent further damage,” said Provincial Administrator Rolly Rosal.

For Masarawag residents, one question looms: Will these suspensions actually ease sudden flooding, or have years of landscape change already created new risks?

Flooding as a recurring trauma

Flood alerts now trigger instinctive fear. “We’ve evacuated multiple times. It’s not just the flooding, it’s the trauma,” said student Janel Bosquillos, who also struggles with noise from heavy trucks.

In Purok 6, vendor Joy Botiquin Orila recalled how the road turned into an overflowing river during a moderate rain, costing her a day’s income.

Pabelona added that they worry about sand and debris from Mayon’s slopes rushing down again.

What upstream inspections reveal

Masarawag councilor Romulo Llona said upland coconut farms now act as overflow channels, directing water toward the barangay center. Maravillas explained that expanding plantations replaced deep-rooted trees that once held slopes in place, while industrial growth has added pressure on already fragile waterways. Residents, including Pabelona, also point to past illegal logging and poorly managed tree-planting as having weakened the mountainside.

The consequences are visible. A sinkhole recently opened in a residential area, injuring a pregnant woman and frightening her elderly mother enough to request relocation.

An inspection by the Albay Provincial Engineering Office (APEO) identified natural waterways and a large gully—about four persons high and four armspans wide—channeling runoff from Mayon. Fresh flood traces were visible during BicoldotPH‘s visit.

Rosal said upstream risks also stem from aging infrastructure and long-term land-use shifts. A sabo dam built in the 1980s is now damaged and may no longer control debris as intended, especially after decades of tree-cutting and slope disturbance. He added that the residential area used to be part of the drainage system, altering water routes, while quarrying in neighboring villages may also be contributing to runoff intensity.

Pabelona reiterated that Masarawag itself has no quarry operations, only dredging and desilting.

Where quarry suspensions fall short

The suspensions aim to assess environmental damage, identify hazardous or exhausted sites, and revoke noncompliant permits before allowing operators to resume. Eighteen operators have already returned, while revoked permittees may haul remaining stockpiles until Jan. 15 to prevent them from being washed away.

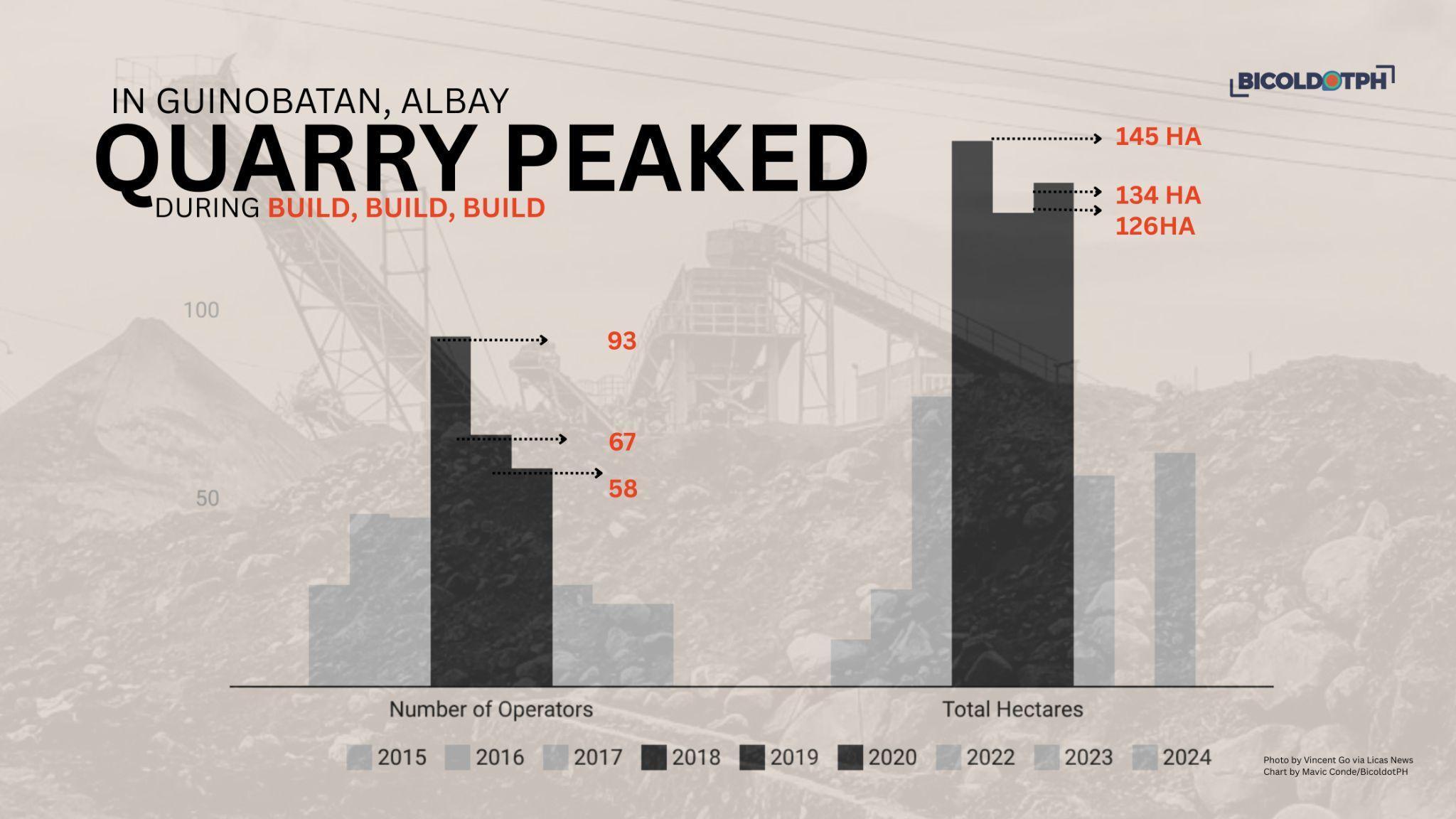

Former governor Al Francis Bichara maintained that quarrying did not cause the 2020 lahar disaster that killed five people and buried 300 houses, arguing that loose volcanic debris was the main culprit. But the Mines and Geosciences Bureau (MGB) records show quarry permits rose sharply during his term. Environmental groups say safeguards such as hazard mapping and watershed rehabilitation lagged behind extraction.

The Philippine Institute of Volcanology and Seismology (Phivolcs) has also noted in past advisories that while poorly monitored quarrying can worsen erosion, removing excess volcanic sediment can help reduce lahar volumes. Operators and some local government units (LGUs) often cite this to argue that quarrying has both risk-reduction benefits and environmental costs, reflecting the complexity of the matter.

MGB data underscores the scale: Guinobatan’s quarry area expanded from the size of 300 basketball courts in 2015 to about 3,450 in 2018. Masarawag permits from 2017 to 2024 covered 70 to 215 courts.

Residents online continue urging stronger action, including reforestation of Mayon’s slopes and stricter limits on what they describe as excessive quarrying. Dikes, they note, have repeatedly failed during heavy rains.

And despite DENR suspending several operations after the 2020 disaster, no comprehensive rehabilitation plan followed.

Stricter rules, but missing pieces

Rosal said new rules now require tighter document checks, a seven-day hauling window instead of 90, monthly inspections, and a ban on nighttime hauling. But the impact of these changes, he cautioned, will not be immediately felt.

The province will now require each operator to assign a technically capable control officer—a measure not previously mandated. Rosal said future permits will prioritize small and medium-scale operations, which are easier to monitor and less likely to cause large-scale disruption.

“Income must only be secondary to pro-environment mining,” he said.

Environmental advocate Adornado Cabaldag warned that quarry profits seldom benefit affected communities and that poorly regulated extraction worsens floods, landslides, and ecosystem loss. He called for “stronger accountability measures and genuine ecological rehabilitation.”

Under the Philippine Mining Act of 1995 and its IRR (DENR AO 95-23), operators must rehabilitate affected areas through erosion control, river-system stabilization, and re-vegetation. But the provincial government has yet to release a public rehabilitation plan or timetable.

Gaps residents want closed

APEO is preparing findings for the provincial government. Llona supports completing Masarawag’s dike system and improving roadside drainage. Environmental groups and church leaders continue calling for transparent monitoring and clear decision-making.

Guinobatan Mayor Ann Gemma Ongjoco said temporary shelters will be prepared should evacuations be needed. Identified families will stay in modular container vans on a provincial lot in Bubulusan village. An earth dike is also under construction in Purok 4 to divert water toward other gullies. A proposed box culvert raised concerns that it would redirect water into another residential area, prompting the LGU to seek technical guidance from the Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) before proceeding.

For now, the town relies on localized evacuations and post-flood clearing. Residents typically return once waters subside. Recent forced evacuations cost the LGU an estimated P2–P3 million.

Barangay officials and residents still await clarity on who will oversee rehabilitation, how progress will be measured, and when updated risk assessments will be released. Until then, vigilance remains their only certainty. “We’re doubly alert every time we’re told to evacuate,” one resident said.

–With additional reports from Vince Villar, Rey Anthony Ostria, Aireen Perol-Jaymalin, Bea Bianca Nicerio and Alexa Obaña

*Editor’s Note: Data reviewed is only from Guinobatan. Be guided accordingly.

*A standard basketball court is about 420 square meters (0.042 hectares).

12.6 hectares ÷ 0.042 hectares/court = 300 courts

*Vince Villar, correspondent for Legazpi City-based BicoldotPH, is a VERA Files fellow under the project Climate Reporting: Turning Adversities into Constructive Opportunities.

This story was produced with the support of International Media Support and the Digital Democracy Initiative, a project funded by the European Union, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Denmark, and the Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation.

The views and opinions expressed in this piece are the sole responsibility of the writer and do not necessarily reflect the views of the European Union, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Denmark, the Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation, and International Media Support.