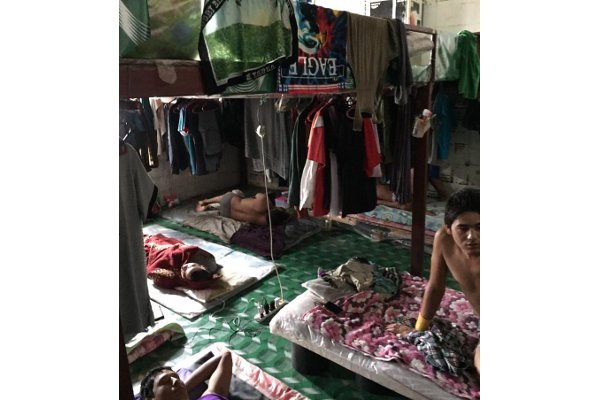

KUALA LUMPUR – The living quarters of migrant workers in Kajang, about 30 kilometres from the Malaysian capital Kuala Lumpur, were like a buffalo cage – dirty and smelly. In a December raid, Malaysia’s Human Resources Minister M Saravanan was shocked and horrified to discover that 751 foreigners, working at a glove-processing factory, were living in two 1.5-metre-tall containers which could only accommodate 100 people.

Living quarters for migrant workers at a glove-making company in Malaysia. Photo from Andy Hall.

Saravanan revealed that nine out of 10 migrant workers in Malaysia were provided with quarters that do not comply with the government’s standards for worker accommodations.

Over in neighbouring Singapore, it was normal until recently for up to 20 migrant workers to be packed in a tiny room with double-decker beds. The cramped space – there were no legal rules on maximum occupancy in migrant workers’ quarters before COVID-19 – made social distancing impossible.

In sum, the COVID-19 pandemic exposed Malaysians and Singaporeans to the appalling living conditions of migrant workers who have been largely invisible in their daily lives.

Their overcrowded, often squalid, accommodation has been a key factor behind the pandemic’s spread in these countries. Thus, COVID-19 drove home the lesson that there should not be discrimination between the social protection of migrant workers and that of the general population as the virus does not differentiate between them, says Adrian Pereira, executive director of the non-government North South Initiative based in Malaysia.

But more than a year into the pandemic, has this led to a greater understanding of migrant workers’ lives among communities in ASEAN’s migrant-receiving countries?

Not quite, say activists pushing for migrants’ rights – although there were initiatives last year that saw Singaporean citizens reach out to migrant workers after reading media reports about how they were being housed.

Nobody cared about the workers’ living conditions because their plight was “hidden” from most Malaysians and Singaporeans, says Andy Hall, a specialist on migrant workers’ rights based in Nepal. “But once COVID-19 came, people realised that the accommodation had an impact on the general population and their health. So, they decided to improve it,” he said.

There has even been a lot of hate speech coming out of social media against migrant workers over the past year, Pereira observed.

“It’s horrific,” Hall said, describing the living conditions of foreign migrant workers in Singapore before the government pushed for proper accommodation for them during the pandemic. “We see workers not allowed out of factories and their living quarters to go to shops because employers have power over them.”

Malaysia and Singapore are major destinations in ASEAN for migrant workers, along with Thailand. The World Bank estimates migrant workers in Malaysia at 3.26 million. From Indonesia, Myanmar, the Philippines as well as Nepal and Bangladesh, they are in domestic work, construction, agriculture and make up more than 20% of the labour force. There are nearly 1.5 million migrant workers, many from the Philippines, Indonesia and Bangladesh, among Singapore’s 5.9 million people. They make up some 37% of its labour force.

Since the COVID-19 pandemic, some reforms have been undertaken. Singapore announced, and said it has started to build, new, less-dense quarters for migrant workers.

The Malaysian government enforced new minimum standards that employers were to follow from Sep 1, 2020 if they provide housing for their employees. For example, a single bed and mattress cannot be shared among workers. The employer must also ensure the availability of water and electricity supply in their living quarters.

But at a time when migrant workers are experiencing renewed discrimination at this time of pandemic, they remain a vulnerable, or even more vulnerable, occupational group.

They have typically been excluded from social protection mechanisms, such as financial assistance given to locals amid COVID-19-caused work stoppages. “Very little was done to ensure they had financial relief, unlike what the government did for locals. Even those not infected by the virus were imprisoned in their dormitories and not allowed to move freely. Many have also lost their jobs,” said Jolovan Wham, a Singapore-based social worker with the Transformative Justice Collective.

Lee Hwok Aun, a senior fellow with Singapore’s ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute, pointed out that the pandemic further exposed the precarious conditions of migrant workers in crises, such as weak legal protection, heavy workloads and poor living conditions. The pandemic brought on added risks, he said, as many migrants work on production lines or in large groups, and could not work from home or find alternative options.

Still, Lee added, there has been some improvement. For example, migrant workers are now entitled to coverage under Malaysia’s Social Security Organisation.

Taking a wider view, Hall said the core challenge is not just about social protection needs exposed by COVID-19, but basic human rights. “When the capitalist companies and governments like Malaysia want workers, they take them. When they don’t want workers, they throw them away,” he said.

“We saw workers without money, without income, but not only that, they were in debt because of all the recruitment fees they paid. COVID-19 showed us that the whole system of migration is completely broken and dysfunctional. And the workers are essentially treated like subhuman,” Hall said, adding that the situation is similar in Singapore.

Since no one is safe from COVID-19 until everyone is, ASEAN has included in its COVID-19 recovery plan a commitment to look into better social protection for migrant workers, including portable health insurance they can use overseas. If it becomes reality, this would go further than the 2017 “consensus” document on migrant workers’ rights that ASEAN has.

While this idea is timely and essential, Lee said: “But as with most things ASEAN, it is hard to feel confident about whether and how the rhetoric will translate into reality.” There is also the challenge of varying standards in countries’ labour laws and social protection.

But it would at least be a start, Pereira said. “This is most welcome as a moral standard and hopefully will be legally binding someday,” he added.

For Hall, the idea is not something new. “They’ve been talking about this issue of social protection, but even within the countries with ASEAN, they don’t have the proper social protection system for their local workers. So the concept of social protection for migrant workers is just so far off to be unbelievably unimaginable,” he explained.

Pereira said that migrant workers constitute significantly to both countries’ workforces and economies, so social protection needs to be operationalized after the pandemic. “I don’t think our leaders have a choice,” he said.

Lee expects employers in Malaysia to lobby fiercely against mandating provident-fund coverage for migrant workers. But since the country already extends coverage to them on workplace accidents and injuries, it should be comfortable supporting this at the regional level, he said.

What kind of social mechanism would be most useful for migrant workers in Malaysia and Singapore?

Lee said: “Governments must lead in setting the agenda and being the intermediating and coordinating authority.”

Pereira said: “We must ensure robust and strong unions in Malaysia, where migrants can play functional roles in them.”

Wham said: “They need to have comprehensive health insurance, and the government needs to do more to cushion the impact of the pandemic on their livelihoods.”

Said Hall: “These social protection mechanisms should be the same as local citizens.”

In Malaysia, the popular COVID-19 tagline is “Kita Jaga Kita” (we take care of each other), while in Singapore, it is “Together we can overcome!”. The “we” should include migrant workers.