September 26, 2009 began just like another rainy day for Corazon Tosio as she saw dark clouds looming over the Marikina River from her house. She knew a storm was brewing. She even knew its name was Ondoy.

And that name would stay with her and with hundreds of families in communities that were battered by the typhoon’s extraordinary rainfall, which drove people up the roofs of their homes and washed away cars and even houses.

Ondoy, known internationally as Ketsana, dumped a month’s worth of rain over parts of Metro Manila and nearby provinces in just six hours.

Ten years to the day, the memories of that disaster are still vivid in many people’s minds.

“We really did not expect it to be that strong because floods have come and gone in our barangay. But Ondoy was really strong. It brought severe flooding,” said Tosio, who was then 49 years old.

Her family had lived in Malanday, one of the most flood-prone communities in Marikina, since they moved to the capital from Aklan province to look for job opportunities decades earlier.

“The flood went up here,” said Tosio, already standing on a tall concrete platform, putting her finger to her neck, an inch below her chin.

The water level in the Marikina River rose to 23 meters above sea level during the flood, which was way above the 16-meter level that would trigger a preventive evacuation of residents around the area.

According to the National Disaster Risk Reduction and Management Council (NDRRMC), then National Disaster Coordinating Council, 464 people died, 529 were injured and 37 were missing as a result of Ondoy.

The estimated cost of damage to infrastructure, which included school buildings and health facilities, was about 4.3 billion pesos while damage to agriculture amounted to 6.6 billion pesos.

Marikina City was “the most heavily affected by flood waters ranging from knee/neck to roof top deep,” according to the disaster agency’s final report on Ondoy.

The Marikina River ten years after disaster struck

The Marikina River ten years after disaster struck

Coping amidst disaster

“It was just me, my husband, and my youngest son at home during the flood,” Tosio said in an interview on the sidelines of a seminar on reporting on women and the environment organized by the Center for Women’s Resources (CWR).

She could not contact her daughter and eldest son, who were away studying and working, because of her phone’s weak signal.

And if weren’t for her neighbor who offered her home’s upper floor as a makeshift evacuation center, Tosio’s family may have suffered more.

“When we got there, everyone was soaked. It was a good thing we brought extra clothes. I gave them the extra clothes of my children and husband,” she said.

“That night, we survived with nothing to eat. I also got worried for my children who were not with me. We weren’t able to sleep all night and morning out of fear because the waters have not gone down yet, and it would rain from time to time.”

When the flood water receded, Tosio went back home to clean the house and prepare food for her family. Her two children had made it back home safely.

“We had to save candles for the night, which was very dark, because there was no electricity. We had to make use of the leftover coal, even though it was soaked from the flood. We had to eat,” she said.

“One of our neighbors got electrocuted. Another one got swept away. I just remember being very thankful that (my children) got home safe.”

After the ordeal, setting up a second floor became the family’s goal. Like many in the neighborhood who built higher, they now feel safer whenever flooding occurs.

It was not the first time Tosio sought refuge from impending danger. Before Ondoy, another typhoon brought vulnerable families living around the river, including hers, to an evacuation center.

“Staying there can be very noisy and messy,” she said, adding that unruly children were all around. “You stay with chickens. The comfort room was dirty and smelly.”

“Also, if a family evacuated at night, they will not get any food for that night. They will have to wait for the next day, because food was rationed,” she shared.

Houses lined in Barangay Malanday with a second floor.

Houses lined in Barangay Malanday with a second floor.

Tosio, now a community volunteer for Gabriela, which promotes women’s issues, talked about the concerns she and other mothers deal with during and after disasters.

Making sure there is food for the family is one. That the house is cleaned up after flooding to avoid bacterial disease is another.

Francisca Inso, 56, another mother from Barangay Malanday, shared Tosio’s experience.

After Ondoy, she admitted she had a hard time providing for her family and taking care of her two children.

“At first, I felt depressed. Then I became anxious and constantly feared for my family whenever there was rain. (My children) would tell me to calm down. This feeling went on for a while,” she shared.

“Of course, I am a mother and a daughter. I have to take care of [my family], especially in times like what happened during Ondoy,” said Inso, who lives with her two children, her husband, and mother. She earns money by selling items, such as shoes and floor mats, to neighbors.

Gender-specific roles pose gender-specific risks

“Women from the marginalized sectors become more vulnerable because they are more likely to be at home during disasters and will put themselves in danger just to save their children and their elderly parents. They are also expected to tend to the sick during post-disaster scenario,” said Jojo Guan, Executive Director of CWR, a women’s advocacy group.

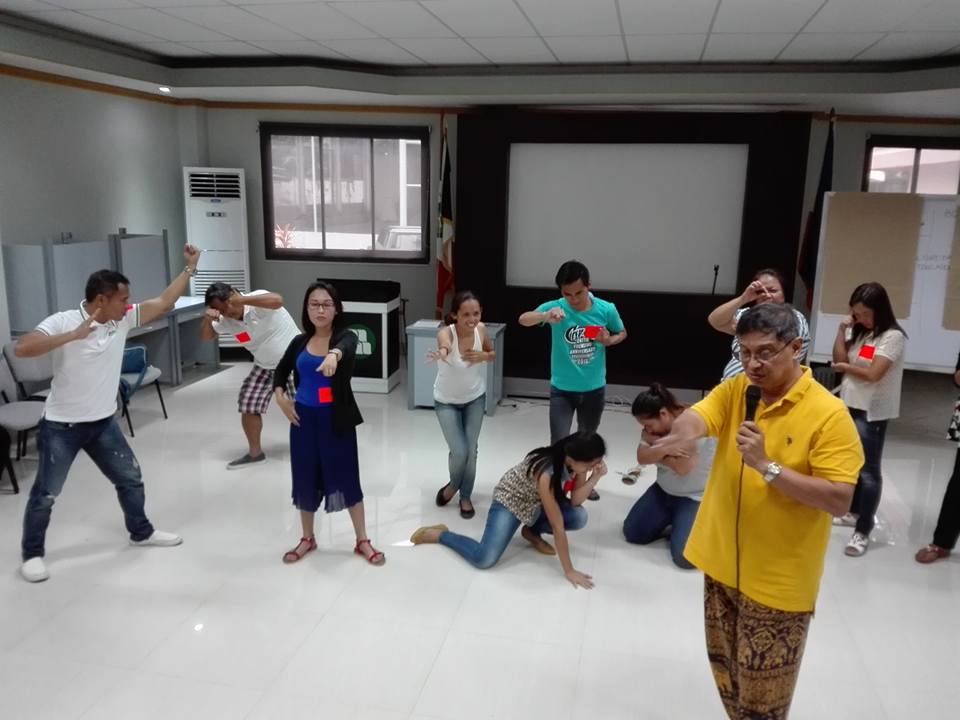

Based on her experience conducting gender sensitivity workshops, Guan has realized that many Filipinos are “unaware of the gender inequality gap.”

“Every time I give the exercise on perception during workshops, I discover a sad reality: Many of them – both men and women – are comfortable with their traditional roles and do not want to stir the status quo.”

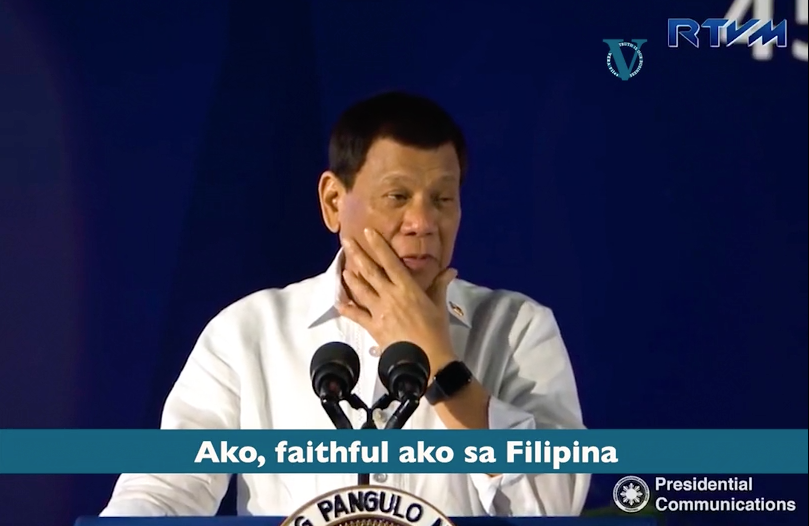

Many traditional women think harassments and abuses are inexplicably part of their gender role, Guan said at the training seminar in Quezon City in late August.

“An ideal woman needs to be compliant, caring, understanding and forgiving towards her man, any action that does not comply with the ‘mold’ is deviant behavior.”

Men, on the other hand, have been brought up to believe that being macho is a characteristic of their gender role, she added.

“Culture plays an important part in the gender inequality gap. And culture is a reflection of who rules or who has the power in society,” said Guan.

In narrowing the inequality gap, Guan encourages men to join gender sensitivity trainings and advocate for women’s rights.

Women must also “study and analyze the social, economic, and political issues in our country so as to know what to demand, what to do, and who would be held accountable during disasters.”

The importance of disaster preparedness

“Each family should have a plan for every disaster,” according to Hanna Fiel, Head of the Research and Public Information Department of the Citizens’ Disaster Response Center (CDRC), an organization which helps to promote community-based disaster management.

Planning for disasters should not be the job of just one family member. “Together, communities or families must do a risk assessment,” Fiel suggested. “Are they easily flooded? Are they prone to earthquakes? Is there a volcano nearby? Will there be a tsunami coming?”

She said her organization helps educate communities. “We gather people to identify their specific hazards at home and in the community. Based on those risks, they will be the ones to pick their safe house.”

According to the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA), the Philippines is ranked third in the 2018 World Risk Index of most disaster-prone countries in the world.

The archipelago bears almost all forms of disasters, from man-made to natural: typhoons, earthquakes, volcanic eruptions and displacement resulting from armed conflict.

“In the Philippines, it is true that many communities have risks. We have communities near rivers, seas, volcanoes, and fault lines but we cannot move them to another place because of a present risk in the community. That would be like checking only one side of the coin,” said Fiel.

“Their livelihood would be at stake. We have to make sure if they will be resettled somewhere that they can have a decent job, she added.

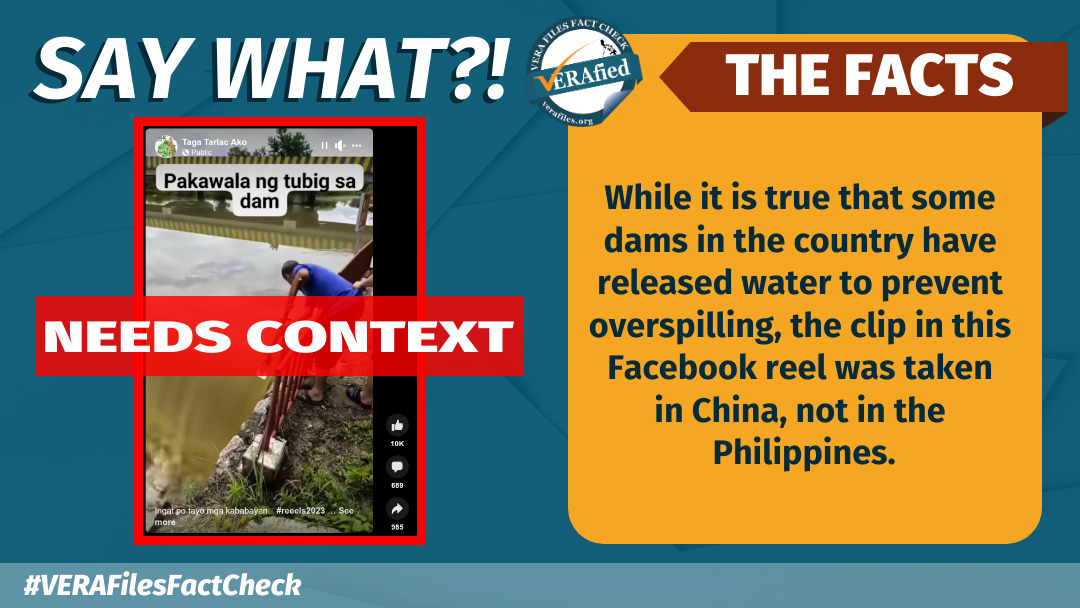

The contents of a go bag: rope (in case people have to cross deep floods), transistor radio, water-resistant cell phone bag, lighter, first aid kit, Swiss knife, medical kit, non-battery dependent flashlight, whistle, emergency blanket, ice pack. Fiel adds clothes, food, water, and important documents should also be stored in the bag.

The contents of a go bag: rope (in case people have to cross deep floods), transistor radio, water-resistant cell phone bag, lighter, first aid kit, Swiss knife, medical kit, non-battery dependent flashlight, whistle, emergency blanket, ice pack. Fiel adds clothes, food, water, and important documents should also be stored in the bag.

“A family should also have a plan on where to evacuate. But it should depend on the kind of disaster. There should also be a meeting point, in case there is no signal.”

Fiel also advised that at least one person in a household is capable of doing cardiopulmonary resuscitation or CPR, an emergency procedure to bring ventilation to another person’s mouth while also delivering chest compressions.

She suggested that each family have a ‘go bag’, which should contain clothes, food, a flashlight, a first-aid kit, important documents “so you will not need to look for them during times of disaster.”

Post-disaster preparedness

“What households should do after the disaster would differ depending on the kind of calamity,” said Fiel.

People should avoid immediately plugging electronic devices right after a flood because they may explode or start a fire, she explained.

“For earthquakes, families should check the integrity of the house before going in because it may collapse. People should also not go inside barefoot, in case glass had been shattered inside.”

After a flood, a family must clean the house to avoid possible infections.

“We believe disasters can be prevented. If not prevented, the effects should be mitigated to minimize damage and casualty rates. That is why we don’t wait to act when there is a disaster. We prepare for it,” said Fiel.

After experiencing many calamities, Tosio now knows the drill. Her usual preparation is to carry liters of clean water, food, and clean clothes up the cabinet. If the rain intensifies, the family takes with them important belongings and flees to an evacuation center.

Tosio considers herself better prepared, with a second floor and a ready bag containing extra clothes for herself and her family.

“Ondoy served as a lesson to me, to our community, the local government,” she said., adding that the situation has greatly improved but the learning continues.

Current SK Chairperson of Barangay Malanday and Ondoy survivor Amen Gandamato said the barangay officials now actively inform residents ahead of disasters by posting public announcements online and via patrol.