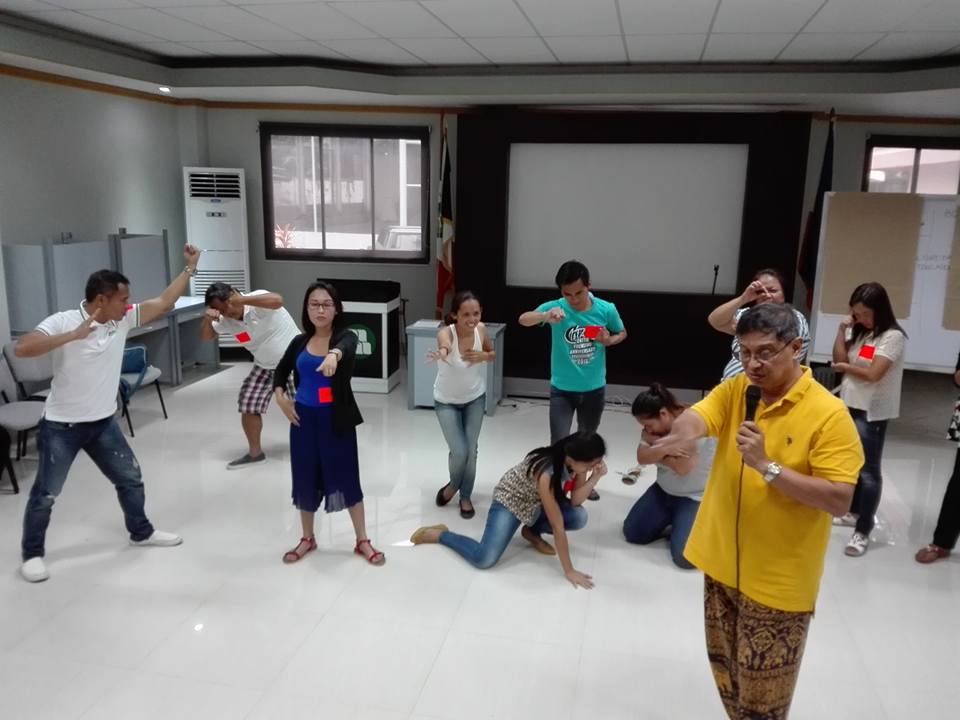

TAGBILARAN, Bohol –Small groups formed various tableaus portraying a family or local community grappling with social or natural environmental hazards or issues.

Later the tableaus were transformed into drama skits—three visual sets illustrating cause, problem and solution, complete with dialogue, music and some dancing.

They were participants in a series of training-workshops held here in October and November focusing on “Culture-based Climate Change and Disaster Risk Reduction Education,” facilitated by local non-government organization PROCESS-Bohol in partnership with the National Commission for Culture and the Arts and Kasing Sining.

It forms part of the Bahandi Bol-anon Kabilin program now adopted with five local government units (Loon, Maribojoc, Cortes, Antequera and Balilihan) as partners “geared towards providing basic skills in communicating basic themes and concerns in Disaster Risk Reduction (DRRM), climate change and heritage protection using arts and culture” as effective communication tools, says Lutgardo Labad, artistic and pedagogy director of the program.

Typhoons are part of life in the Philippines. As 2016 closes, the Philippines had experienced 30 typhoons and an almost daily earth tremor, said resource speaker Oscar V. Lizardo, chief information officer of Project Noah.

The Philippine archipelago being on the typhoon belt and the “Ring of Fire” is the third “most exposed” country to natural hazards worldwide, according to 2016 World Risk Report, produced by the United Nations University, the University of Stuttgart and Bündnis Entwicklung Hilft, an alliance of German aid agencies.

It trails behind Vanuato and Tonga, which ranked first and second, respectively, on the list of the 15 “most exposed” countries to natural hazards—such as volcanic eruptions, typhoons, and earthquakes.

Exposure to hazards does not automatically make a community vulnerable to disaster, according Lizardo.

But if the community is poor and with less capacity to manage itself, then it will always be “victimized” by natural or manmade hazards. “If an area is exposed to hazards, not all [people there] are vulnerable, but the poor are,” he said.

Vulnerability, he added, could also be due to “various physical, social, economic and environmental factors, such as poor design and construction of buildings, inadequate protection of assets, lack of public information and awareness, limited official recognition of risks and preparedness measures, and disregard for wise environmental management.”

He gave tips to effective communication, such as, making the information visual, localizing both the language and images of the information, preferably with the participation of the “most influential” in the community, using ambassadors (stars, etc.), and being creative in communicating.

Nestor de Veyra, a rural sociologist of Save the Children involved in community-based disaster risk management in Leyte, shared lessons learned from the experience with typhoon Yolanda on November 8, 2013. He said the lack of proper communication of the effects of “storm surge” had a disastrous impact in the area he operated at the height of typhoon Yolanda. “If they just used “tsunami”, even if it was not the right technical term, then the people would have been alerted,” he said.

Lizardo stressed the importance of an accurate hazard map, noting that in the case of Leyte in when Yolanda struck, “70% of evacuation centers in Tacloban were hit by storm surges,” a fact that reflected the inaccuracy of the hazard map presented. Good hazard maps always indicate safe areas for development, and safe areas for evacuation if necessary.

There was also a presentation of folk culture augmenting the capacity of communities to prevent disasters.

In the 2013 earthquake in Bohol animal behavior warned the local folks of the tremor. Fisher folks of Tubigon town noticed the simultaneous flying of herons in the mangrove forest seconds before the earthquake. The flapping of wings of the wild pigeons (camaso) alarmed folks of the quake in barangay Toril, Maribojoc.

The belief of guardian spirits in particular mangrove, mountain forests and springs are factors for the conservation of coastal and mountain environments, some for centuries, These have effectively prevented massive flooding of communities in those areas.

Ignoring such beliefs that control resource use have dire consequences, as shown by flashfloods brought by typhoon Senyang rains in 2014 that flowed from the river tributaries of Abatan River.

Research of some areas affected by earthquakes has shown that some buildings and houses constructed with traditional community technique and materials have proven resilient to quakes when well maintained, he observed.

The community practice of “dajong” (to carry/help) in many parts of Bohol had been applied not only to those who have a relative who dies, but also in emergency situations like the 2013 earthquake. In the absence of electricity, some communities used the native “tingko” and “kuratong” (bamboo community calling devices).

Herbal plants and traditional massage, in the absence of first aid kits, were used for those injured, sick and stressed in the 2013 quake in Maribojoc.

Some common sense traditional wisdom, like not locating the house near a river bank or a community near the coastal area, especially where the river meets the sea, have been ignored, he said, with disastrous consequences, citing the examples of Moalong village in Loon town, and Busao in Maribojoc.

Cultural workers were urged to take a look at the traditional forest-related knowledge and associated management practices which have been transmitted from generation to generation, especially how to cope with local climate shifts and impacts of extreme weather, knowledge related to weather prediction, of wild plant and animal species and their management, and agricultural techniques to manage and conserve water and soil resources.

After the inputs, the participants were asked to get into multi-media creative improvisations incorporating climate change and disaster preparedness, and local heritage and knowledge as sources of content in awareness and education drives through action, music, theater and the visual arts.

Each participant was then asked to draw in a piece of a puzzle board a visualization of his or her pledge of action related to climate change and disaster risk reduction, after which all the puzzle board paintings merged into one mosaic painting.