Text and photos by YVONNE T. CHUA

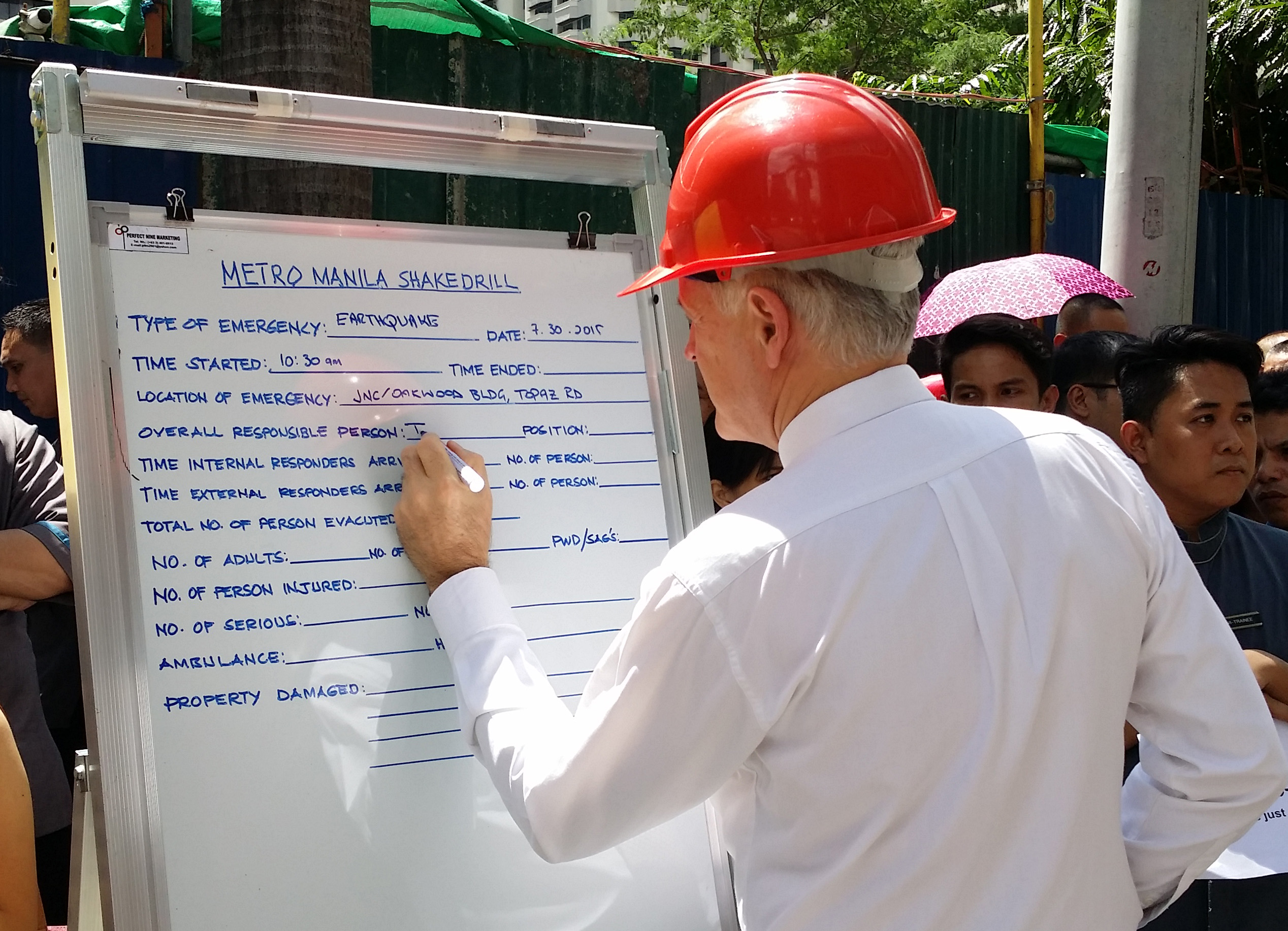

AT 10:30 a.m., the hotel emergency alarm went off, signaling the start of Thursday’s “Shake Drill” designed to prepare Metro Manilans for a 7.2 magnitude earthquake or the “Big One.”

Many of the 30 or so guests meeting at the hotel’s fifth-floor function room quickly stood up and gathered their belongings. As some headed toward the door, an announcement in English blared over the PA system, reminding them to stay put and to drop, cover and hold.

Most did as told. But it took three guests slightly longer to do so: They were blind and had to be assisted to the floor.

Five others, all of them in wheelchairs, meanwhile, covered their heads with their hands.

In about a minute, the second announcement came: Evacuate the building.

The hotel staff requested everyone who had no disability to leave the room right away.

They would, they assured the group, take care of “extricating” persons with disabilities: the three blind guests, the five wheelchair users, an amputee who uses crutches—and one who passed himself off as a deaf person to test how well equipped the hotel was to evacuate persons with disabilities in case of a disaster.

And that was how Oakwood Premier Hotel in Ortigas, Pasig discovered it wasn’t, not even with the disaster training its staff had undergone just two weeks ago.

The reality check came from no less the leaders of disabled people’s organizations (DPOs) and disability advocates whom The Asia Foundation had gathered for a briefing on the Australian government’s disability strategy.

Had the TAF held the meeting in another hotel, the results would probably have been the same.

As the guests exited Oakwood’s function room, deaf community advocate Arthur Allan Ponce dashed to the waitstaff and began signing as he pretended to be deaf. When he couldn’t get his message across, he used finger spelling. One of the waiters then led him to the fire escape—and left him there.

Unguided, Ponce made his way down to the ground floor where he approached the hotel’s “fire tenders,” again signing to them that he needed help. Apparently at a loss over how to deal with him, the tenders turned their backs on him.

Meanwhile, he could hear the announcements coming over the PA system or being shouted to guests. He observed the hotel had no lights to guide people with hearing disability had power been cut, and no sign cards with graphic warning to tell them and the other guests where to seek shelter.

“If this had happened at night, I would have been dead,” Ponce, of the Philippine Accessible Deaf Services, said after the half-hour drill.

Back at Oakwood’s fifth floor, the hotel staff gingerly led the three blind persons one by one out of the function room, down through the fire escape to the ground floor. All of them are from the Adaptive Technology for Rehabilitation, Integration and Empowerment of the Visually Impaired (ATRIEV) who had gone to the meeting with just one companion.

But when they reached a supposedly safe place, “they just left me there,” said Atriev’s Carol Catacutan. “They didn’t endorse me to someone else.”

Evacuating the five wheelchair users from the fifth floor proved the most challenging for the hotel. The five waited patiently outside the function room as hotel personnel discussed among themselves how to carry them down five flights of stairs one at a time. The hotel has a spine board but didn’t use it in the drill.

Only two employees lifted the hefty Dennis Ilagan, president of the Cerebral Palsied Association of the Philippines, out of his wheelchair and carried him down the fire escape by the armpits and legs. The employees paused at every stair landing to catch their breath and switch positions as they felt the strain in their arms.

They eventually got Ilagan out to the street where a medic took his blood pressure. But hotel employees left his wheelchair on the fifth floor. This was brought down when the other wheelchair users firmly explained why Ilagan needed it.

“When the person gets to an accessible place, he’ll use the wheelchair to wheel himself to safety,” said AKAP-Pinoy’s Abner Manlapaz, who also uses a wheelchair.

Two hotel employees would also later carry Ilagan’s wife, Grace, down and out of the building. But she was apprehensive throughout the rescue.

She could sense the employees’ panic and exhaustion. One of them had muttered, “Pagod na ako (I’m tired).”

Every time their grip on her slackened, Grace feared they would drop her and she might injure her spinal cord. “Please, not a spinal cord injury. I already have cerebral palsy,” she said.

Grace said she was lucky Shelly Thomson of Australia’s Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade was nearby when she was being moved.

Thomson, who was in Manila to give briefings on Australia’s disability strategy and conduct disability training, showed hotel employees the correct way of carrying a PWD like Grace.

Unlike the Ilagans, Manlapaz refused to be bodily carried. He insisted on being brought down in his wheelchair.

His instruction was clear: Four people were needed to carry his wheelchair. The hotel assigned two. As they wended through the narrow fire escape, Manlapaz persuaded two more employees to help.

Out on the street, hotel guests found the first staging area was right under trees and an electricity post in front of the looming luxury hotel, instead of at the open-air parking lot adjoining it which was a safe zone.

In the end, the other two wheelchair users—Charito Manglapus of CPAP and Bianca Lapuz of the Commission on Elections—stayed behind on the fifth floor. Manglapus uses an electric wheelchair and Lapuz a wheelchair scooter.

Manglapus would say later that it would have been not only difficult but also dangerous to carry her down the way hotel staff did with the other wheelchair users because she can’t cross her arms.

Later in the day, when things quieted down, Oakwood Premier general manager Trevor MacDonald personally thanked the PWDs and disability advocates for the valuable lessons the hotel unexpectedly learned first hand during the drill.

For Thursday’s drill, the hotel staff learned only at 10 a.m.—half an hour before the metrowide drill—that they would also be evacuating PWDs. This after the PWDs at the TAF meeting declared that they were joining the drill which, they said, should be disability inclusive.

Already considered by many disability advocates as PWD-friendly, the hotel was convening a special meeting that afternoon to discuss how it can better respond to disasters, especially for persons with disabilities, MacDonald said.

TAF Deputy Country Representative Maribel Buenaobra and other disability advocates suggested disability sensitivity training not only for Oakwood but for other hotels, especially for first responders.

The government’s National Council for Disability Affairs runs such courses, including how to extricate people with different disabilities during emergencies.

The courses teach one- to four-person carry for persons with mobility problems, communicating through signing, writing or lip reading for those who are deaf or hard of hearing, and guiding blind people to safety, among other things, said NCDA’s Delfina Baquir.

Disability advocates also stressed the importance of providing instructions in Filipino or the vernacular, and in graphics.

But there’s an equally important thing to bear in mind when rescuing PWDs during disasters. Said Manlapaz: “Ask PWDs how they want to be assisted.”