(First of two parts)

A loud, hornlike sound blares from the Marikina River. Restless families living at the flood-prone Balubad Settlement in Nangka, Marikina City start packing their bags and brace for possibly a second warning sound that would signal their evacuation.

Despite the fear they create, warning sirens have become indispensable to over 451,000 residents of Marikina, who were caught unprepared by tropical storm “Ondoy” (Ketsana) whose torrential rain spawned record-high floodwaters that killed nearly 464 people in Metro Manila — 68 of them in Marikina — in late September of 2009. Records show the typhoon destroyed over 18,000 houses and caused P384 million worth of damage.

The city has learned its lesson: Twelve sirens are now installed along the riverbanks to serve as an early warning system. This and other disaster-related measures the local government put in place in the aftermath of Ondoy have turned the effort into a multi-awarded disaster resilience model in the country and abroad.

But because the sirens can only be heard, they are of no help to those who cannot hear, like 22-year-old Rodelyn Gacute.

Marikina has installed 12 sirens along its

riverbanks as an early warning system, but not one would help persons with

hearing disabilities like Rodelyn Gacute.

A person with hearing disability, Rodelyn has had to depend only on her mother, sampaguita vendor Zoraida Gacute, who signals her of impending floods. Only then does Rodelyn, the eldest of seven, proceed to pack their clothes and wait for the signal to leave.

This has been their ritual of survival, the mother serving as the daughter’s lifeline. Had there only been an early warning system in visual format that could reach her deaf child, Zoraida would not have had to worry. But until there’s one, the only recourse is to always keep Rodelyn in her sight–especially when disaster strikes.

“She has to be where I can see her at all times so I wouldn’t have to worry and look for her. Whatever happens, at least we are together,” she said in Filipino.

For a disaster resilience model, Marikina City ironically falls far behind the ideal in terms of preparing one of the most vulnerable sectors — people with disabilities (PWDs) — for disasters. Not only are alarm-based warnings inaccessible to some PWDs, the city also failed to capture all PWDs in its roster. With only 7,000 registered PWDs out of an estimated 10,000, some are in constant danger of being missed out during evacuation, rescue and relief operations — proof of how the welfare of PWDs continues to be overlooked in the city’s lauded efforts. This, despite laws safeguarding their welfare during disasters.

Protection for the vulnerable

PWDs are classified as vulnerable along with women, children, the elderly and ethnic minorities in Republic Act No. 10121 or the Philippine Disaster Risk Reduction and Management Act, which calls them “differently-abled people.” (“Persons with disability” is the appropriate and disability-sensitive term to use.—Ed.)

The United Nations Convention on the Rights of PWDs (UNCRPD), to which the Philippines is a signatory, also provides for the protection and safety of PWDs in natural disasters.

Marikina received the Gawad Kalasag Award

from the Office of Civil Defense in 2013 for its efficient early warning

system. A single sound of the warning sirens varies in length and frequency,

depending on the alert level.

In 2013, Marikina received the Gawad Kalasag Award from the Office of Civil Defense (OCD) for its efficient early warning system. A single sound of the warning sirens varies in length and frequency, depending on the alert level. The water level during Ondoy was recorded at 23 meters. Had the warning system been in place then, the alert level would have been at 4th alarm signaling forced evacuation, and sirens aired non-stop.

Besides exposure to flooding, parts of the city also sit directly atop of the 100-kilometer West Valley Fault, whose movement could trigger a 7.2-magnitude earthquake, or “Big One.”

Rodelyn’s mother, Zoraida, knows her small home in Nangka may collapse should that happen.

When her daughter experienced a 3.6-magnitude earthquake once, Rodelyn panicked and shouted the name of his father, Zoraida said. Fearing for their safety, Zoraida makes sure her daughter is always within reach.

“Kailangan nandiyan lang siya. Para nakikita mo. Para hindi ka mag-aalala. Asan na? Hindi ka na maghahanap.. Kahit ano mangyari, at least sama-sama (She has to be where I can see her at all times so I wouldn’t have to worry and look for her. Whatever happens, at least we are together),” she said.

Marikina’s multi-awarded early warning system limited to audio signals

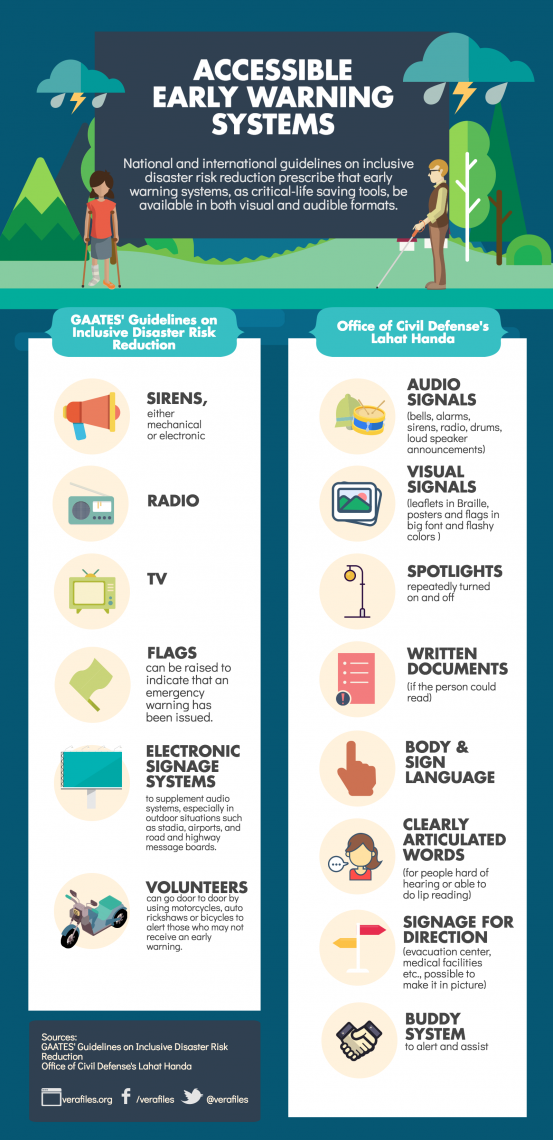

To cater to all types of disability, national and international guidelines prescribe other formats such as the posting of a notice in a community center, hoisting of a red flag, broadcasting warnings on television and radio or a word-of-mouth information program.

However, in the three most disaster-prone barangays of Nangka, Tumana and Malanday, early warnings are limited to audio signals in the form of sirens, bells, whistles, public addresses, text messages and door-to-door rounds of first responders.

Early warning systems should be available in both visual and audible formats, according to Canada-based Global Alliance for Accessible Technologies and Environments (GAATES). It has published guidelines on disability and disaster based on research conducted in the Philippines, Myanmar and Sri Lanka.

The study noted that in the Asia Pacific Region, “very little has been done to make disability-inclusive early warning systems.” Most disaster announcements are delivered primarily in an audible format, and this doesn’t meet the needs of people with hearing disability, it added.

In a 2015 interview with the authors, Val Barcinal, then-head of Marikina City Disaster Risk Reduction and Management Office (MCDRRMO), said he had considered hoisting flags above the rivers in addition to sirens fixed on high poles. But the plan didn’t push through when he found it inconvenient to assign someone to wave the flags every time there’s a disaster.

Pilot lights alongside sirens were also considered, but Barcinal said it would entail much effort in terms of localizing the system per barangay, which “operates independently” from the city.

Trauma from Ondoy lingers 8 years on

An accessible early warning system, however, is only one of the indicators of an inclusive disaster management.

Useless as it may seem to deaf people like Rodelyn, the sirens pose a different effect on children with intellectual disabilities like 16-year-old Marvin Orona of Barangay Tumana.

Sirens are intended to alert Marikina residents of the possibility of evacuation, it triggers Marvin, who has alearning disability, of a traumatic experience. (Authors obtained permission to use photo.)

Each time the first alarm is raised over the Marikina River, Marvin trembles and yells at his two younger siblings to start packing their bags. “Dalian niyo na! Andyan na iyong tubig, mataas na (Hurry! The water’s rising)!” he would say, running around their home situated across a creek beneath the Tumana bridge.

Then, he would reach for his bag and stuff it with some clothes, textbooks, pencils, and his most prized toys. He would cling to them tightly for the next few hours or so—until the rain ends.

The series of loud sounds coming from the siren remind Marvin, who has global developmental delay (GDD), of his traumatic experience during Ondoy.

As floodwaters rose to the ceiling of their two-story home, his mother, Maria, hurried to bring her three children, one after the other, atop the roof. All of them obeyed willfully except Marvin. Drenched in rain and silent tears, the child had to be grabbed by the wrists and shoved to the roof.

How Marvin would be able to save himself during a disaster remains Maria’s biggest fear as a mother of a PWD. When it comes to comprehending the idea of disasters, Maria admits her child would have difficulty.

Mateo Lee, deputy executive director of the National Council on Disability Affairs (NCDA), said children with learning disabilities like Marvin are not flexible to changes in routine.

Training them to grasp the idea of disasters would take months, even years, he said. Even if the parents have training on how to handle their children during disasters, warning alerts are only sent a day or two prior to evacuation. It is not that easy to change the child’s routine),” Lee said in Filipino.

Disaster management councils, he said, must work on training rescuers on handling different disabilities and communicating with immediate families of PWDs. But it must be a constant practice, as disasters may occur anytime.

Survival as ‘a matter of luck’

Marikina City conducts regular trainings for first responders, but none so far has been devoted to handling different types of disability, the DRRMO confirmed.

In April 2015, the city integrated in one of its trainings some safety precautions for PWDs during earthquakes.

Gil Flores, who heads the Marikina PWD Affairs Office (PDAO), attended the training. PWDs were told to try, as much as possible, to reach the ground floor using the stairs, or run to the nearest beam of a building if they are unable to exit the premises.

Flores, a wheelchair user because of his orthopedic disability, counts himself lucky to have learned such precautionary techniques. But even after the training, he still fears getting stuck on a high building when an earthquake strikes.

It’s all a matter of luck: “Talagang siguro kung aabutin ako (ng lindol), gagapang na ako pababa ng hagdan (When an earthquake strikes, maybe I would end up crawling downstairs).”

Several earthquake drills have been conducted in anticipation of the “Big One,” but none has been designed for PWDs despite physical barriers to mobility.

In Nangka, where Rodelyn lives, the barangay officials created a video on safety during disasters. But only when it was shown before PWDs did the officials realize the video, lacking subtitles, wasn’t fit for deaf people. The officials forgot to hire a sign language interpreter.

‘Missing’ PWDs

In the event of a disaster, first responders would prioritize PWDs like Rodelyn and Marvin, who are accounted for in the city’s records as registered PWDs. But PDAO’s Flores said Marikina still has to reach out to at least 3,000 PWDs who have not yet been registered to the city’s PWD database.

Hernando Laurio, or Bokbok to his neighbors, is one of them. The 23-year-old who has autism is usually seen wandering around the low-lying creekside compound of Libis, Malaya in Barangay Malanday.

Bokbok

to his neighbors, Hernando Laurio, who has multiple disabilities, loves to walk

around the community, which worries his sister in case a disaster happens.

A few steps away from Bokbok’s house, 23-year-old John Gwendol Santos or Aaron, who has intellectual disability, often observes outsiders in silence from a window. He does not like to mingle with a crowd. In fact, his father, Salazar, remembers how angry he got while walking back and forth, when a fire hit a nearby community.

The barangay’s PWD database includes neither Bokbok nor Aaron, as they are not registered PWDs.

A barangay official said one way to include PWDs in disaster management is by putting stickers outside their houses to identify and prioritize them, but the effort does not go as far as to include those invisible in their database.

Both the city and Malanday’s databases are unreliable, with some names repeated as many as four times. They also lack vital information such as the disability and the address, which is important in addressing the needs of PWDs.

According to the GAATES guidelines on inclusive disaster risk reduction management, an updated registry of PWDs is an effective way to identify people within a community that might need assistance in an emergency. It also stressed that governments must work on public awareness campaigns, piggybacked on municipal mailings or announcements to invite people to register their names, location and individual needs.

Only when there is data can the DRRMO determine areas with the highest concentration of PWDs, as well as map the exact locations of those directly vulnerable to floods and earthquakes, said Barcinal. Or else, the former disaster management officer pointed out, plans to include Marikina’s registered PWD population in disaster preparedness efforts will be kept in limbo.

In the meantime, family members of PWDs have no other choice but to keep them close. “Iyong pinagaalala ko sa kanya kasi ganyan siya, hindi niya alam…pag nangyari na iyon at mag-isa lang siya, parang matutulala na lang (I worry that because of his disability, he wouldn’t know what to do if he’s alone in case the disaster strikes),” said Marvin’s mother, Maria.

When the shaking begins and people are running and shouting in the distance, Maria is certain that her son won’t be able to move around. “Sigurado akong hindi ito (makakaalis) kunwari nadatnan siya sa school (I’m sure he wouldn’t be able to seek refuge in case it happens in school),” she said. “Kaya (dinadasal) ko sana ‘pag nangyari iyon, sama-sama na lang kami rito sa bahay (I’m praying that when it happens, we’re together, at home).” (To be concluded)

(This report is based on the authors’ undergraduate thesis, “Critical Point: An Investigative Study of the Inclusiveness of Disaster Risk Reduction and Management Programs of Marikina City for Persons with Disabilities” done under the supervision of University of the Philippines journalism professor Yvonne T. Chua. VERA Files is put out by veteran journalists taking a deeper look at current issues. Vera is Latin for “true.”)