(Conclusion)

Five Septembers after tropical storm “Ondoy” (Ketsana) took the lives of 68 people in Marikina City and left P384 million worth of damages, the city was again placed under a state of calamity in 2014 when tropical storm “Mario” (Fung-Wong) submerged eight barangays, forcing people out of their houses to safety.

Before all the chaos, Alma Maurillo, who has low vision due to glaucoma meningitis, voluntarily evacuated to a primary school 650 meters away from her home in Balubad Settlement in Barangay Nangka. She and other residents of the flood-prone barangay had mastered this drill.

The treasurer of the barangay’s persons with disabilities (PWDs) association, Maurillo knows PWDs are supposed to be housed on the first floor of Nangka Elementary School, along with senior citizens and pregnant women.

Having difficulty climbing stairs, she waited for hours in front of the room for the door to be opened, pleading to stay on the ground floor. Barangay officials denied her request.

Staying on the first floor of the evacuation center would have been easier for Nangka, Marikina resident Alma Maurillo, who has low vision due to glaucoma meningitis. However, simple requests like that, which could have made the lives of PWDs easier, are not always granted.

Maurillo is just one of the over 7,000 registered PWDs in disaster-prone Marikina who will need temporary refuge when a calamity strikes. Some of them, however, would rather stay with relatives or generous neighbors, if any, due to inaccessible shelters. Despite local and international laws securing the right of PWDs to accessible facilities during disasters, none of the city’s three most disaster-prone barangays of Nangka, Tumana and Malanday have required in their disaster management modules the lodging of PWDs on the first floor of evacuation centers or the allocation a separate room exclusively for the sector.

Despite 35-year-old law, schools in Marikina not accessible to PWDs

In the absence of permanent evacuation centers and shelter sites in Marikina, 31 primary and secondary schools have been the go-to sites during calamities due to their reachability and capacity to accommodate a large number of people.

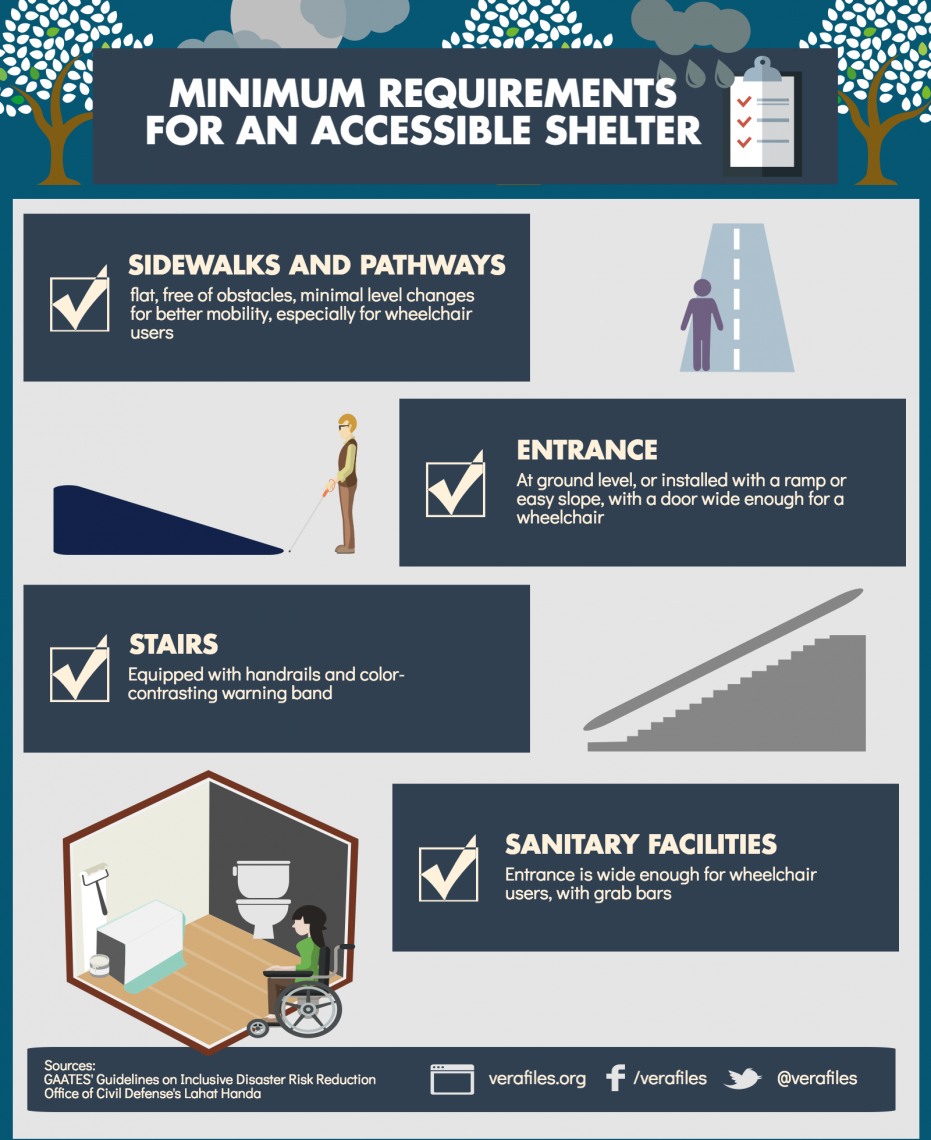

Intended for public use, schools are mandated to be barrier-free by Batas Pambansa 344 or the Accessibility Law. The 1982 law aims to enhance the mobility of PWDs by requiring public and private buildings and public facilities to provide accessible features such as ramps.

For one, doors should have a minimum clear width of 0.80 meters, to allow the entry of wheelchairs, which have usual width of 0.60 to 0.75 meters. Portalets, which are often used in evacuation centers, usually do not fit this specification.

“Paano makakapasok ang naka-wheelchair (sa portalet)? Eh kahit naman sa hindi disabled hindi pa rin siya humane (How can wheelchair users go inside portalets? It’s not even humane for regular people),” Mateo Lee, deputy executive director of the National Council on Disability Affairs, said.

Passed in 1991 and amended in 2012, Republic Act No. 7277 or the Magna Carta for PWDs emphasizes the rights of the sector, but it lacks provisions on the welfare of PWDs during humanitarian emergencies.

In the absence of a law, disaster mitigation agencies in the country, as well as abroad, have developed several guidelines on inclusive disaster risk reduction, which include provisions on accessible shelter sites and evacuation centers.

In 2016, the Office of Civil Defense (OCD) and international aid organization Handicap International launched “Lahat Handa,” a supplementary module to the basic instructor’s guide for disaster responders.

The Lahat Handa prescribes the use of contrasting colors in doors, signages, and even in stairs, as it helps those with visual disabilities.

Supposedly safe shelters, Marikina schools still exposed to flooding

Lahat Handa also provides for protection mechanisms in evacuation camps, which include help desks, express lanes, priority sleeping areas and a mobile clinic, all of which shall have a PWD volunteer to man the booth, and assistive devices like wheelchairs, crutches and hearing aids.

But since there are no wheelchairs at Concepcion Integrated School (CIS) in flood-prone Barangay Tumana, 19-year-old Patty Boy Berzo, who has orthopedic disability, would end up lying on a makeshift bed in the evacuation center should there be a disaster.

In the

event of a disaster, wheelchair user Patty Boy Berzo prefers to leave his

nonfoldable wheelchair at home, in the absence of ramps and lifts in the

nearest evacuation center.

His wheelchair, a bulky and non-foldable one borrowed from a family friend, would be left at home because there are no ramps at the CIS. “Without [the wheelchair], he’s not able to do anything. He has no choice but to just lie down. We don’t let him go around because we’ll just have a hard time,” Delia said.

The international module “Guideline on Inclusive Disaster Risk Reduction: Disaster and Disabilities,” prepared by Global Alliance on Accessible Technologies and Environments (GAATES) discourages leaving assistive devices like wheelchairs and white canes.

“When evacuating persons with disabilities in disaster situations, their assistive devices, or means of communication and walking aids should not be left behind,” the document said.

NCDA’s Lee said the wheelchair, for instance, is part of the PWD’s “personal dignity.” That is why evacuation centers must be equipped with assistive devices.

Accessible facilities are a requirement, but the government needs to start investing in designated permanent shelter sites that follow universal design, said Edward Ello of Handicap International.

Universal design refers to “the design of products environments, programs and services to be usable by all people, to the greatest extent possible, without the need for adaptation or specialized design,” according to the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (UNCRPD).

Relief packs are one size fits all

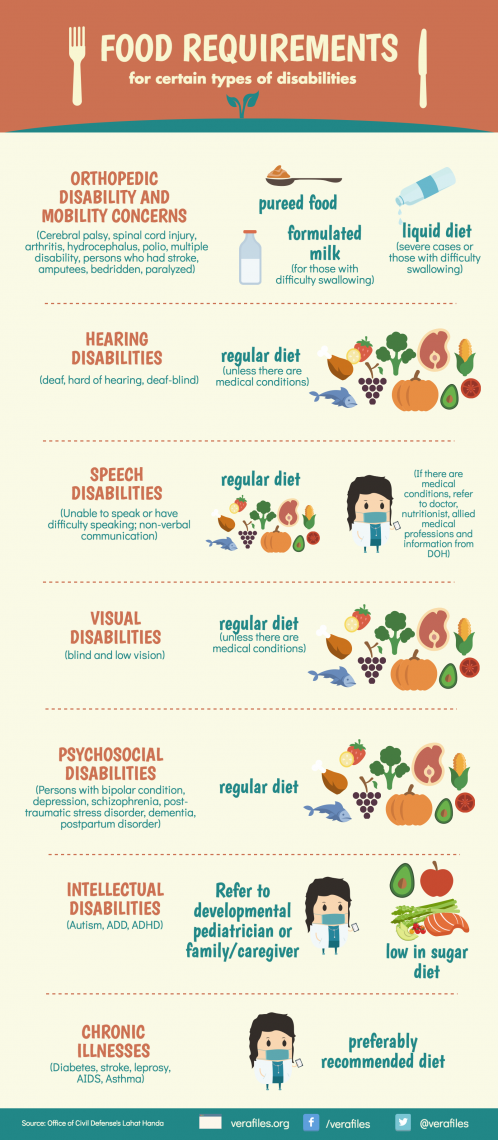

The quality and variety of relief goods distributed in evacuation centers should also be improved, as they may pose harmful effects to the physical and behavioral health of children with disabilities.

Inside a relief pack prescribed by the Social Welfare Department are the following: six kilos of rice, four cans of sardines, four cans of corned beef, four sachets of coffee or cereal energy drink. This would feed a family of five in two days, according to former Social Welfare Secretary Judy Taguiwalo.

“Certain types of disability require certain nutritional requirement. May mga bata na hindi lagi pwede bigyan ng gatas, chocolate. Nagiging hyper sila (Some kids must not be given milk or chocolate at all times because they become hyperactive),” NCDA’s Lee said.

According to Lahat Handa, soft diet must be provided for people with mobility issues, specifically those who have difficulty swallowing. Food for people with intellectual disabilities such as autism, Attention Deficit Disorder (ADD) and Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) must be low in sugar.

Alternatives suggested by Lee include boiled eggs, bananas, bread and rice porridges. But to do that, he said one will need a mobile kitchen.

Not just objects of charity

Both Lee and Ello also believe PWDs who are capable of rescuing themselves can be trained to contribute to disaster management.

Most people fail to see the capacity of PWDs, who are often perceived as people who need priority, Ello said. When trained, some PWDs can also provide rescue to family members.

The attitude change must come from PWDs themselves, he added. “Dapat marunong din sila mag-advocate ng rights nila, hindi yung tipong charity (They must know how to advocate for their rights, and not just rely on charity).”

Read first part here.

(This report is based on the authors’ undergraduate thesis, “Critical Point: An Investigative Study of the Inclusiveness of Disaster Risk Reduction and Management Programs of Marikina City for Persons with Disabilities” done under the supervision of University of the Philippines journalism professor Yvonne T. Chua.)