By VERLIE Q. RETULIN

It was Aug. 2, 2014 when Ron, 27, arrived in Norway. Her host family welcomed her warmly at the airport and then took her to their home where dinner was waiting for her.

Ron had gone to the Scandinavian country as an au pair, made possible through a cultural exchange program. She was there to learn about the culture and language of the host family and would be given free lodging and food in return for doing light household chores such as washing the dishes and taking care of her host’s children.

Things were going well for Ron who described her hosts as smart and fair and who treated her like she was part of the family. Then in January, her host dad lost his job and had to terminate her contract, saying he could no longer support an au pair.

“That’s when my problems here in Norway started,” Ron said.

Ron was introduced to her new host through a Norwegian agency—a divorcee with four children who lives in a 15-room mansion worth about 10 million Norwegian krone or P57.8 million.

Instead of treating her as an au pair, the divorcee turned her into a maid.

“I signed a contract to help with light housework and not to do general cleaning every day. I signed a contract to work five hours a day, not nine,” Ron said.

Ron’s experience shows that Filipino au pairs in Europe are still subjected to labor exploitation despite revised guidelines issued by the government in 2012 regulating their deployment and putting in place safety nets to shield them from abuse.

The 2015 Trafficking in Persons (TIP) Report released recently by the U.S. State Department noted that many Filipinos overseas are victims of forced labor, some lured through email and social media, with illegal recruiters using student, intern and exchange program visas to circumvent regulatory frameworks.

Au pairs are young unmarried persons without any children, usually between 16 and 30 years old. They are mostly female. The French word means “on par” or “equal to,” which denotes living on an equal basis in a mutual, caring relationship with the host family and the children.

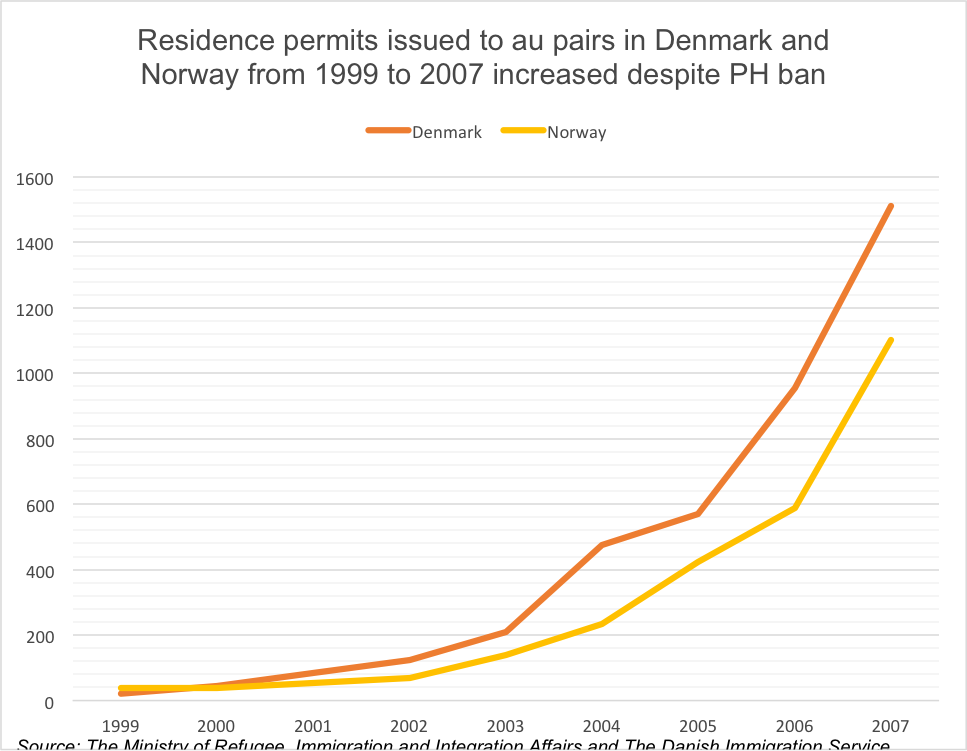

The Philippines has been participating in the au pair program since 1969. However, in 1998, the Philippine government imposed a ban on au pair migration following increasing reports of labor exploitation and sexual abuse.

In 2010, the decade-long ban was lifted in Denmark, Switzerland and Norway, which signed bilateral agreements with the Philippine government. In 2012, it was lifted in all European countries after the New Guidelines on the Departure of Au Pairs to Europe were issued by the Technical Working Group composed of the Department of Foreign Affairs, Department of Labor and Employment, Department of Education, Bureau of Immigration, Philippine Overseas Employment Agency and the Commission on Filipinos Overseas (CFO).

The 2012 guidelines transferred the responsibility of handling the au pairs from POEA and DOLE to CFO since they are not considered as Overseas Filipino Workers.

In addition, au pairs will be required to attend a Country Familiarization Seminar before leaving the country to equip them with information about the host countries and to serve as a monitoring scheme for au pairs leaving the country.

However, in November 2014, two years after the implementation of the guidelines, Vice President Jejomar Binay urged the DFA and the Philippine Embassy in Copenhagen to investigate a report from the Danish labor union, Fag og Arbejde (FOA), that Filipina au pairs in Denmark were being abused.

According to the report, nine of 10 au pairs complaining of abuse from their host families are Filipinas.

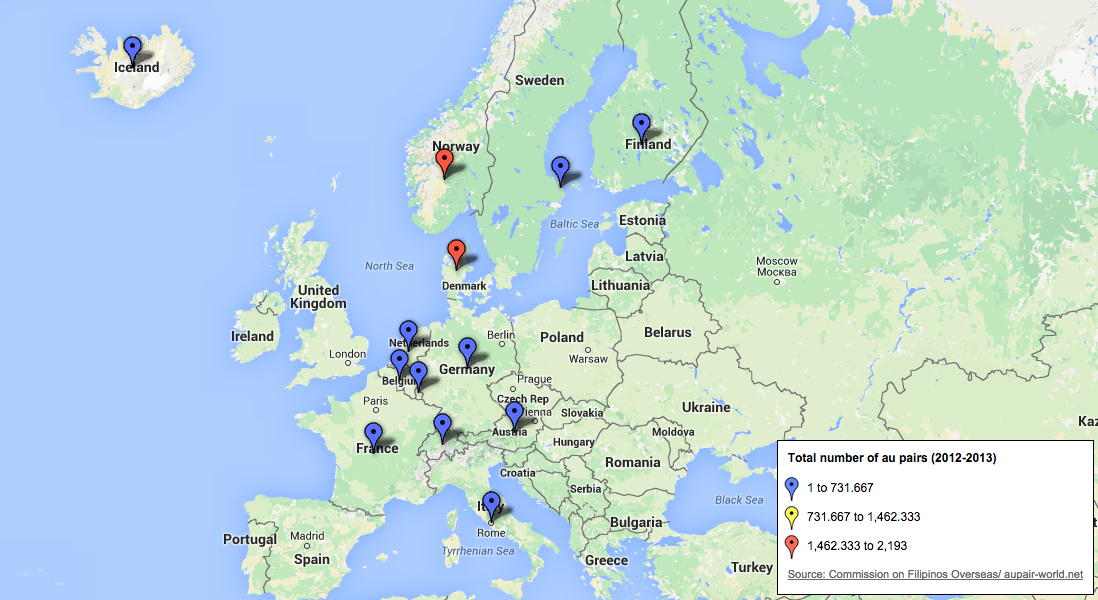

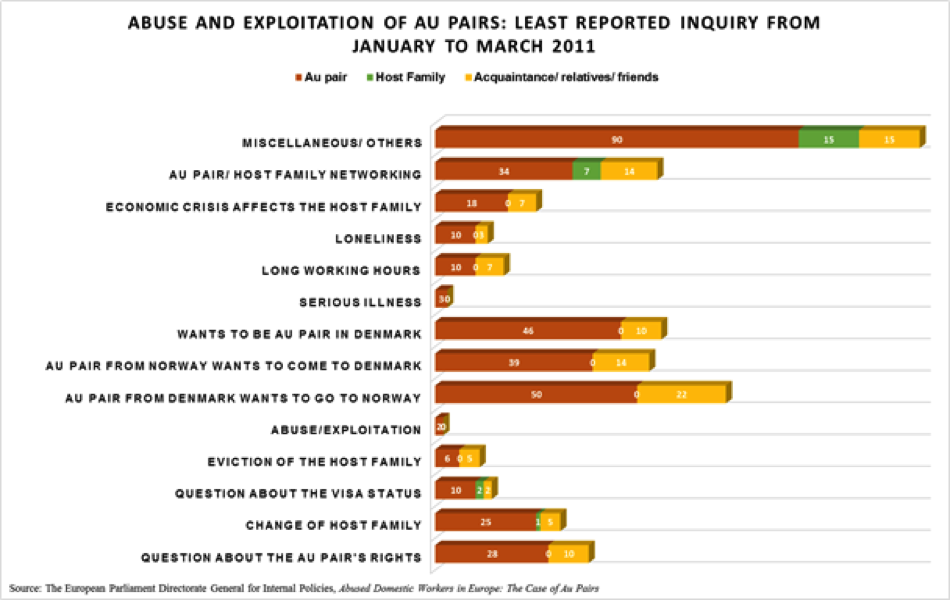

Earlier, in 2011, the Danish Refugee Council (DRC) reported that they received 1,000 calls per year, 60 percent of which were from au pairs and 40 percent from the host family. It also said majority of the 60 percent were Filipinos.

Out of the 371 inquiries that DRC received from January to March 2011, only two of them were related to abuse and exploitation.

Peter van Zoeren, Policy and Advocacy Advisor of the Center for Migrant Advocacy, said, however, it is difficult to provide the actual number of abuse experienced by Filipina au pairs.

“It’s massively underreported. A lot of abuse and exploitation has happened, but the Filipina au pairs won’t report it,” he said.

Filipinas who complain to the authorities run the risk of getting their contract terminated and face deportation if they fail to find another host in one to three months, Van Zoeren said.

Ron confirms Van Zoeren’s statement. Although she has filed a complaint against her second host, she knows of at least two other similarly situated Filipina au pairs in Norway who refuse to go to the authorities.

Contracts are supposed to ensure legal protection for au pairs.

“The contract is a legal basis for the au pair which provided them with legal protection. Therefore, it is important to have an extensive contract that covers as much as it can,” Van Zoeren said.

But many contracts are far from ideal. For example, although the Norwegian contract highlights the au pair’s rights, it only stipulates the punishment for au pairs who engage in illegal work: revocation of residence permit and expulsion from Norway. The contract is silent on punishment for the host family should it abuse an au pair.

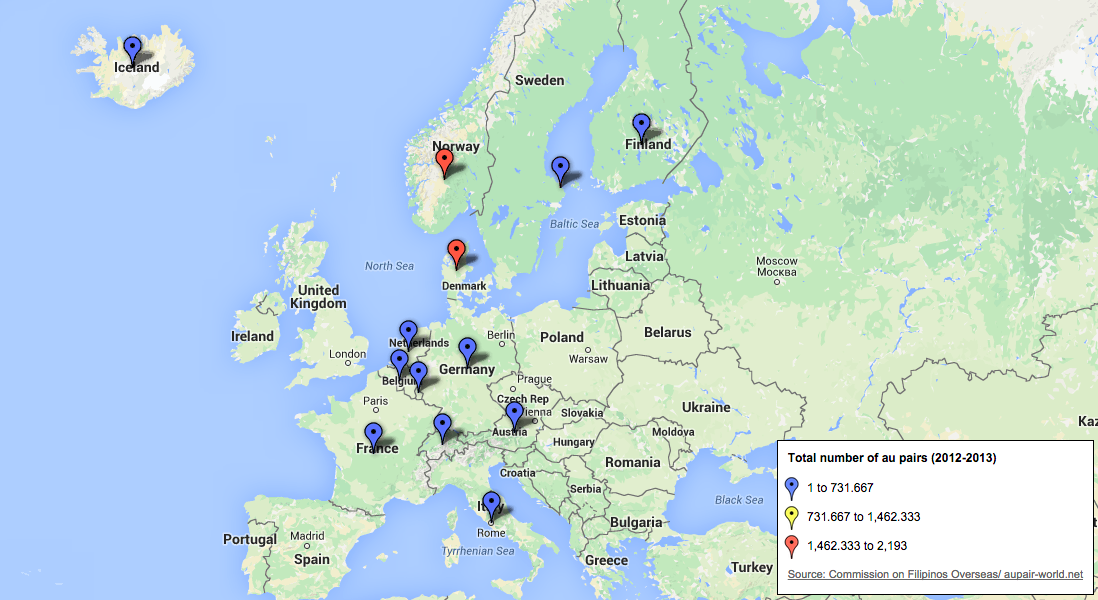

Denmark and Norway were the leading countries of destination for au pairs in 2012 and 2013, according to the data provided by CFO. Forty-two percent of Filipino au pairs went to Denmark and 41 percent to Norway. One out of 10 Filipino au pairs preferred to go to the Netherlands.

Even during the ban, records reveal a consistent and rapid increase in the number of au pair residence permits issued to Filipino immigrants in Denmark and Norway from 1999 to 2007.

Based on the combined data from the Ministry of Refugee, Immigration and Integration Affairs and the Danish Immigration Service, the average annual increase of residence permits issued to Filipino au pairs from 1999 to 2010 was 57.4 percent.

“The Philippine government can’t tell a European government to close or open their borders to a certain type of worker or au pair,” Van Zoeren said. “For instance, if an au pair, during the ban went to the Netherlands—it is perfectly legal. From the (Philippine perspective, however,) that would be an undocumented and illegal way of leaving the country.”

(The author is a journalism student at the University of the Philippines-Diliman. She submitted this story for the data journalism course taught by VERA Files trustee Yvonne T. Chua.)

INTERACTIVE MAP:

Or click here to see map in a bigger window: