If there’s one thing that makes singer,

actress, and television host Jolina Magdangal jumpy, it’s zooming vehicles.

“If there’s a vehicle speeding past us or a

fast-moving bus, I just pray for the people inside it. It’s like they have death

hanging over their heads!” she says in Filipino.

The feeling of anxiety is not irrational. Magdangal,

her husband musician Mark Escueta, and their firstborn son, five-year-old Pele,

are road crash survivors.

The family and their driver were headed to

the airport early morning on July 10, 2017, and while waiting for the red light

to turn green on an intersection along East Avenue in Quezon City, a passenger

van hit the rear of their SUV.

The impact left the Magdangal-Escuetas’

bumper and back window smashed. Jolina took home a nasty bump behind her head

while Mark experienced upper body pain.

Pele, safely secured in his front-facing car

seat, was unharmed.

Magdangal, who popularized a song called Bahala Na (Come What May), knew it was

not luck, but the decision to strap her then three-year-old son in a car seat, that

saved him from injury.

When the couple bought the toddler’s car

seat, there was no ordinance mandating them to have one. Magdangal and

Escueta’s P10,000 investment was a personal choice that paid off. It kept Pele

safely in place the whole time of the crash.

A new law signed in February by President

Rodrigo Duterte now makes it imperative for all private vehicle owners to have

child restraint systems (CRS) in place for those traveling with children, and

restricts minors aged 12 and below from sitting in the front seat.

Speaking at a press conference on March 19 in

Quezon City, Magdangal urged parents to support the law – Republic Act 11229 or the Child Safety in Motor

Vehicles Act – and at the same time called for more affordable car seats.

“That’s one of their reasons they cite [for

not buying one], ‘It’s too expensive. I can carry my child.’ They don’t realize

that this is a good investment because it’s their kids’ lives on the line,” said

Magdangal.

“But I do hope there will also be car seats that are cheap but tough,

so people will use them and everybody can follow the law.”

Transport officials, road safety experts and advocates discuss the Child Safety in Motor Vehicles Act.

Seats

that save kids’ lives

Pele wasn’t the only child in the scene.

Magdangal said once her anger dissipated, she

went down from their vehicle to check on the van’s passengers. To her surprise,

one of them was a mother cradling a baby.

The baby seemed fine, and it appeared that

the kid was carried by its mother the whole time, the actress related.

“The baby’s okay,” she recalled the mother

saying.

But among children who are involved in road

crashes, few are as lucky as the child inside the van that morning two years

ago.

Road traffic injuries are now the leading cause

of death among children and young adults (aged five to 29) worldwide, according

to the World Health Organization (WHO) Global Status Report on Road Safety

2018.

In the Philippines, it’s the fourth leading

cause of death for children aged five to nine, Department of Health (DOH) data

shows.

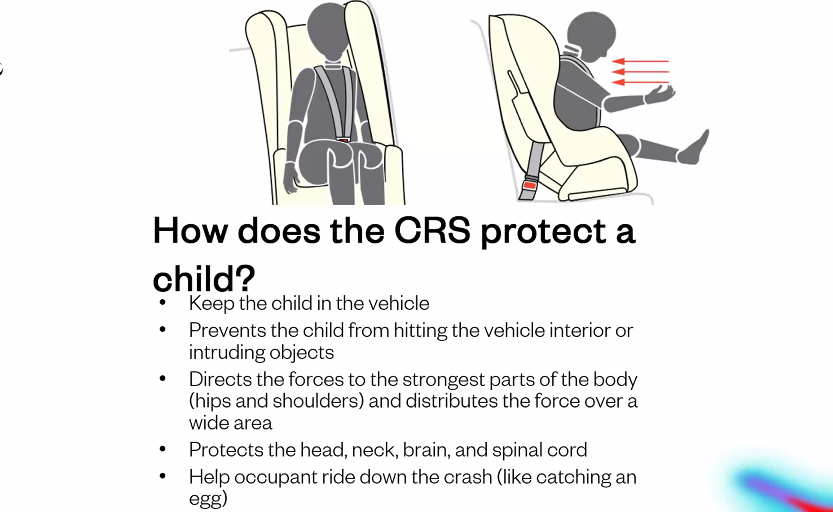

Designed to accommodate a child’s height,

weight and stage of development, CRS protect children from collisions, sudden

stops and swerves by restraining a child’s movement and distributing the forces

of a crash to the stronger points of a child’s body.

A WHO manual on seat belts and road safety says a

regular vehicular seatbelt “may lead to abdominal injuries among children, and

will not be optimally effective at preventing ejection and injury” because of a

child’s different build from adults.

“Studies have shown that (CRS) really

protect, they protect against deaths by as much as 70% among infants and among

older children by as much as 54% to 80%,” says Dr. John Juliard Go, WHO

Philippines’ program officer for road safety and non-communicable

diseases.

RA 11229, specifically, requires children

aged 12 and below, standing less than 4’11”, to be transported in car seats.

Additionally, the law also makes it illegal for children in the same age and

height range to sit in the front seat of the vehicle.

In the Magdangal-Escueta family’s case, Pele

had been in a front-facing car seat appropriate for his age at the time of the

crash – one meant for kids aged two to six years – that was placed in the car’s

rear seat.

Influenced by relatives and friends from the United States who visit the country and immediately seek out CRS for their kids, Magdangal says she cannot drive around without her children being secured by CRS. Her nine-month-old daughter Vika also uses a car seat that’s rear-facing.

“For me, it’s like you’re betting on ‘bahala na‘ (come what may). It seems you’re hedging your bets on that and you’re lucky if nothing happens to your child.”

Affordability an issue

Compliance with RA 11229 is set to become compulsory a year after the Department of Transportation and several agencies finish drafting its implementing rules and regulations, which the law has given them six months to do.

This gives plenty of time for the government, road safety experts and advocates to resolve an issue affecting support for the law: car seat affordability.

Magdangal recalls that Pele’s booster seat during the crash was worth around P10,000. (Escueta has said in a previous report that it was actually P17,000).

Pele uses the same seat he had been in at the time of the collision, after it was found to be still in good condition after a post-crash check-up by its manufacturer.

While built for durability and long-time use, the car seats’ steep prices keep parents from purchasing them.

A study on car seat affordability and availability by the University of the Philippines Manila – Philippine General Hospital headed by its Institute of Health Policy and Development Studies director Dr. Hilton Lam found the average price of brand new car seats sold in malls was P8,864.52; brand new child seats online were at P5,755.44, while second-hand car seats also found online were priced on average at P3,535.

Philippine Red Cross’ Rhea Munsayac demonstrates how to use a car seat for toddlers.

Philippine Red Cross’ Rhea Munsayac demonstrates how to use a car seat for toddlers.

As a general rule, however, WHO’s Dr. Go says parents are discouraged from using a second-hand car seat unless they know its history.

“If it is handed down within the family and has not been involved in a crash, then it can be put to good use because its quality remains intact.”

But he cautions that a car seat should be replaced 10 years after its manufacturing date.

The average price of a brand new seat is beyond what parents in the study said they were willing to spend, which ranges from P1,000 to P5,000. Respondents in the study, however, were optimistic that with the passage of the law, mandatory compliance would mean more supply in the market, and eventually lower prices.

Magdangal, who has been traumatized by the car crash, she said her children’s car seats provide her the comfort and assurance when they’re traveling.

“It’s not good for me or for other parents to be paranoid inside the car. We don’t get to rest. But because of the (kids’) car seats, in a way, I am reassured about their safety.”

She said she hopes parents would invest in their children’s CRS because their lives are at stake.

“Money can be saved, spent and can be saved again if we work hard. But our children’s lives cannot be replaced.”

This story has been produced with the help of a grant from The Global Road Safety Partnership (GRSP), a hosted project of the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC).