Public consultations for the draft implementing rules and regulations (IRR) of the child-restraint law will be held in August this year.

Lawyer Evita Ricafort of ImagineLaw, a public-interest legal group involved in drafting the IRR, also said the final regulations are expected to be released on September 2019, with full implementation of the law starting on September 2020.

“Usually, the government releases the draft online and they will also announce the exact date and place of the public consultation,” she said at a June 27 VERA Files forum in Quezon City.

“And usually, the DOTr (Department of Transportation) will also issue invitations to stakeholders, road-safety advocates, consumer associations and probably parents’ organizations that are already involved in road safety,” Ricafort added.

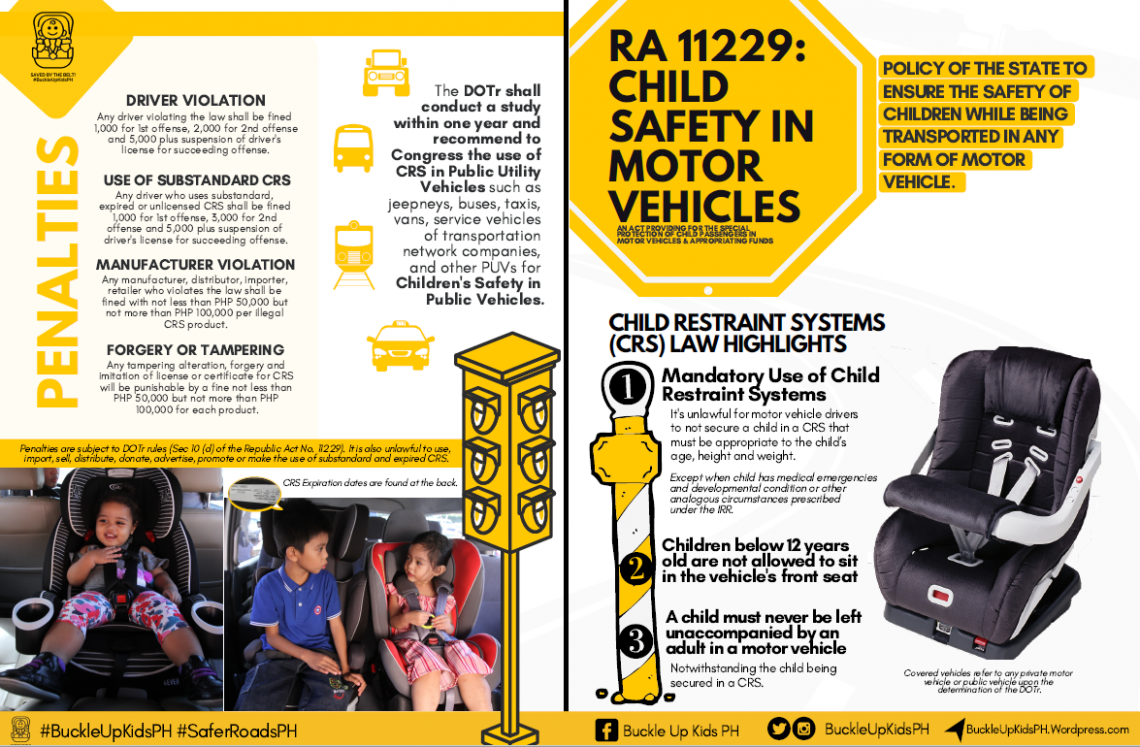

President Rodrigo Duterte signed into law Republic Act (R.A.) 11229 or the “Child Safety in Motor Vehicles Act” on February 2019.

The law requires private-vehicle drivers to ensure that passengers who are 12 years old and younger that are 4’10” and shorter are secured with child restraints when riding a car. It also states that only passengers who are 13 years old and older can use the front passenger seat.

Ricafort said the DOTr may also open online consultations to allow more people to give suggestions.

Parents’ concerns

The consultations come amid concerns over the proper implementation and the expenses that come with following the law.

“Concerns about the cost may also be referred to in the IRR, if there are going to be ways to bring down the cost for Filipinos,” Ricafort said. “In other jurisdictions, there are rental schemes, there are loan schemes.”

In a June 2019 forum conducted by non-government organization Initiatives for Dialogue and Empowerment through Alternative Legal Services, Inc. (IDEALS), parents pointed out how the law could be a big burden, even for well-meaning parents.

“Hindi kasya ang three car seats sa car [Three car seats won’t fit in the car],” mother-of-three Mitzi Barrios told VERA Files at the forum. “Dalawang lang ang kasya, so kailangan ba namin ng bagong sasakyan? [Only two can fit, so do we need to buy a new car?]”

The parents also noted the need to ensure child safety in public-utility vehicles, which are vital for families that cannot afford cars.

Section 9 of R.A. 11229 states that the DOTr must conduct a study to determine whether or not child restraints could be used in PUVs.

“Kung ‘yung families magco-commute lang talaga, sana yung mga PUVs, magkaroon ng car seat,” Mitzi’s husband Dominic told VERA Files. “Dapat nasa kanila yung burden, not doon sa family.”

[Translation: If families could only commute, I hope that PUVs would also have car seats. The burden should be on them, not on the family.]

‘Highly effective’ vs. top killer

R.A. 11229 is one of the government’s responses to what the World Health Organization (WHO) called the top killer of people aged 5 to 29 years old worldwide – road crashes.

The 2018 WHO Global Status Report on Road Safety also found that four in five road-traffic deaths around the world in 2016 occurred in middle-income countries like the Philippines.

The international group said child restraints are “highly effective” in reducing injury and death to child occupants, with the greatest benefit for children under four years old.

For children 8 to 12 years old, the WHO said using booster seats reduced the risk of injury by 19 percent compared to just using a seatbelt, which is normally designed for adults.

PH ‘model’ in child-restraint legislation

Ricafort also revealed at the forum some aspects of the draft IRR, such as a nationwide public-information campaign and guidelines for child-restraint manufacturers and resellers.

“This will actually be the first part of implementing the law: how they would be able to get the approval for the safety standards,” she said.

Ricafort also said the draft outlines child-restraint training programs, as well as clearer rules on the law’s exceptions.

“There will be training for enforcers, there will be the process for the inspectors of the DOTr on how this law will be implemented, there will be training for fitting stations where the public may be educated on how to properly install and how to properly use child-safety devices in their vehicles,” she said.

“What falls under this exception of medical emergencies and for children with medical or developmental conditions who may be exempt from the law, what they need to do, what they need to comply with,” Ricafort added.

Australian engineer and child-restraint expert Michael Griffiths hailed the law, saying at the forum that the Philippines has the potential to become a “model” in child-restraint legislation for developing countries.

“There are some things that the Philippines is already doing better,” he said. “You have a program to train police in the enforcement role. We never had that in Australia and because of that, they never really offered much support.”

Griffiths also praised the Philippines’ efforts to prevent counterfeiting of child-restraint standards stickers, as compared to the paper stickers used in his country.

“Your standards stickers are much more difficult to counterfeit,” he said. “We’ve had problems in Australia with counterfeit stickers. That’s a lesson that we could learn.”

This story was produced with the help of a grant from The Global Road Safety Partnership (GRSP), a hosted project of the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC).