Chennelyn Almonguera already knew about car seats for children even before the safety measure was signed into law last month but she was not keen on buying them for her two kids, aged five and two. She was not convinced the child restraints can protect them in the event of a road crash.

“I’m just scared that something might happen and I will not be able to take hold of the kids”, the 29-year-old mother said in Cebuano, expressing the belief of many Filipino parents that kids are safer in their arms.

Janelle Bascon, 24, on the other hand, has not heard of car seats until she migrated to Canada with her 11-month-old baby.

The Cebu native, who is home for a visit, recounted: “I only got to know that kids need car seats when I got there. Even newly born babies will not be released by hospitals without car seats”.

The country took a huge leap towards ensuring the safety of children on the road with the enactment of the Child Safety in Motor Vehicles Act, which requires the use of car seats and prohibits a child from sitting in front of a vehicle.

Republic Act 11229, signed by President Rodrigo Duterte last Feb. 22 but made public on March 12, mandates the use of child restraints that are appropriate to the child’s age, height and weight. These are car seats, booster seats or car beds designed to diminish the risk of injury to a child because they limit a child’s mobility in the event of a road crash or a vehicle’s sudden stop.

Car seat vs. a mother’s embrace

While Almonguera and other mothers in the country think embracing their kids will protect them, studies prove that this is more dangerous than helpful. In an event of a collision, the pressure from the mother’s arms could crush the child’s fragile frame, health experts say.

Worldwide, 95 countries already have laws requiring the use of car seats. Of this number, 53 countries are said to meet the best practices on child restraints, according to the World Health Organization (WHO).

Now that the use of car seats is a law, Almonguera says she will comply, even if it means an additional expense for the family. “If they made such a law, that certainly means it’s for us, for our kids’ safety. We can look for money, but not life,” she said.

While buckling up children is already a standard practice in many countries, it has not gained popularity in the Philippines because of a lack of awareness of child restraints, the preferred practice of embracing kids while traveling and what some say is the steep price of a car seat.

A study conducted by the Institute of Health Policy and Development Studies in the University of the Philippines Manila (UP-IHPDS) reveals that the average price of car seat in the country is five thousand pesos, an amount many say is “too expensive” for common Filipinos.

Atty. Melisa Jane Comafay, advocacy officer for the Global Road Safety Project of IDEALS (Initiatives for Dialogue and Empowerment through Alternative Legal Services Inc.) admits that raising public awareness of the importance of child restraints is one big challenge advocates like her will have to address.

“Safety of the children is the primary objective of this law, it’s not to make them spend more but it’s the actual safety of their children. It’s not the cost but the cost of the life of your children,” Comafay explained.

Road safety champions have also argued that a car seat will come out cheaper than medical bills that may have to be incurred in the event of a road crash.

Under the law, drivers who refuse to use car seats on private vehicles will be fined 1, 000 pesos for the first offense, 2, 000 pesos for the second offense, and 5, 000 pesos and the suspension of the driver’s license for one year for the third and succeeding offenses. RA 11229 also prohibits leaving children alone in the vehicle and allowing children 12 years old and below to sit in the front seat unless the child is 150 centimeters (4’11”) in height.

Instead of focusing on the penalties and the additional cost of buying a car seat, Comafay is urging parents to look at the safety of their children instead.

Why use car seats?

Road traffic injuries are now the leading cause of death for children and young adults aged 5- 29 years old. Approximately 1.35 million people die each year as a result of road traffic crashes around the world according to WHO’s 2018 Global Status Report on Road Safety.

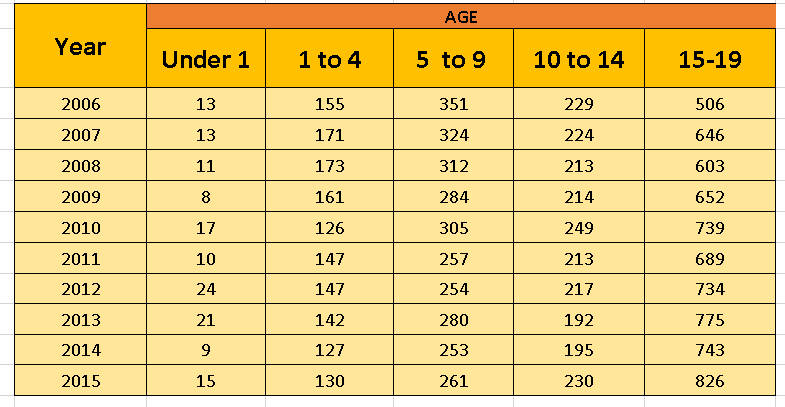

In the Philippines, an average of 671 children aged 14 and below died each year from 2006 to 2014 from road crashes, according to the Philippine Statistics Authority.

With their small size and limited physical, social and cognitive development, children are at high risk for traffic injuries, says the WHO. Seatbelts are not enough.

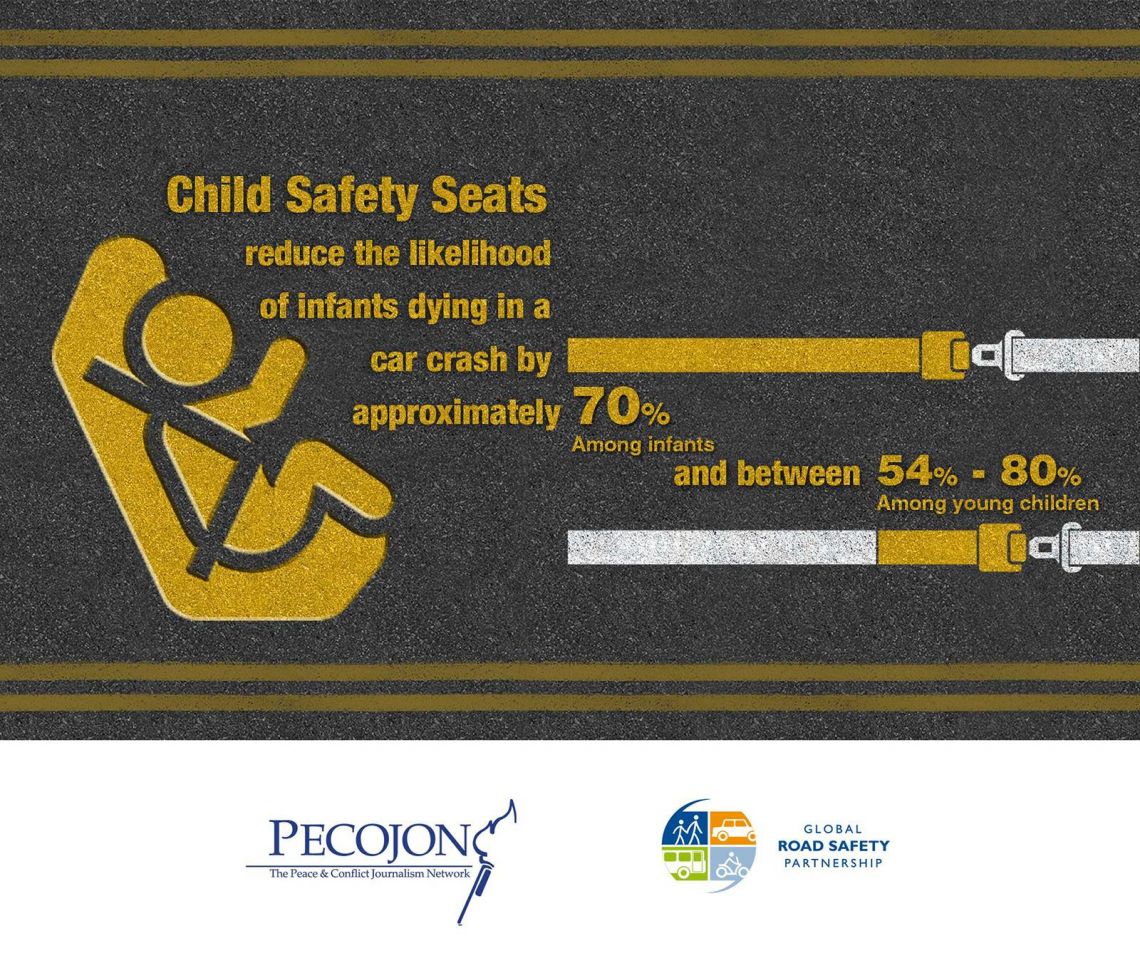

To reduce the risk of injury and fatalities on children, the use of appropriate child car seats is needed. Car seats reduce the likelihood of a fatal crash by up to 70% among infants and 54-80% among children, it says.

CHILD SAFETY ON PUBLIC VEHICLES

The law requiring the use of car seats for children is very helpful, according to 23-year-old Zash Mariez del Pilar, who has a two-year-old kid and a four-month-old baby.

Though her parents have a car, she often travels with her kids using public transport. She is hoping that a similar law would be created and enforced to keep children in public vehicles safe too.

While RA11229 covers only private vehicles, it orders a study on the feasibility of adopting the same measure for public utility vehicles (PUVs) in order to protect child passengers.

Under Section 9 of the Child Safety on Motor Vehicles Act, the Department of Transport (DOTr) is mandated to “conduct a study and recommend to Congress the use of child restraints in public utility vehicles such as jeepneys, buses, including school buses, taxis, vans, coasters, accredited/affiliated service vehicle transportation network companies and all other motor vehicles used for public transport”.

If the DOTr determines that car seats are not applicable for certain PUVs, it shall recommend to Congress other safety measures to ensure child’s safety in vehicles, the law says.

Atty. Ismael Garaygay III, head of the Cebu City Transportation Office, supports safety measures for passengers of public vehicles as there are more crashes in the city involving PUVs, the primary mode of transport in the city.

He is hoping that better safety measures would also be put in place for public transportation such as jeepneys, motorcycles, and taxis.

Director Victor Caindec of the Land Transportation Office (LTO) in Region 7 says their office had taken part in the finalization of the Child Safety in Motor Vehicles Act, yet he also acknowledges that there is a lot more to do to prepare the country for the new law.

“What is very important to note is that this law is patterned after international traffic safety standards. I always believe that whatever law our lawmakers pass would always be a step in the right direction.”

Among the issues that need to be addressed, Caindec says, is integrating the use of car seats into the public transport system and convincing parents of private vehicle owners to comply with the new law.

“If we talk about safety in general, not everyone even follows the seat-belt law. If we now add one more requirement … that is another problem to be dealt with,” he pointed out.

“It is not to say that there is no desire to support … to ensure that the law is properly passed, but those are practical and real challenges,” Caindec added.

In terms of enforcement, the LTO director admits that the agency has not enough budget to further expand its law enforcement capability in terms of manpower. To solve this, he said they maximized their deputation power. LTO 7 has deputized more than 400 PNP officers to help in its operations.

Passenger van terminal in Cebu City. Photo by: Zii Wenceslao

Cebu City has an existing ordinance that prohibits children aged seven and below from riding on motorcycles unless the child’s foot can reach the standard foot peg and the child is able to wrap his or her arms can wrap around the waist of the driver.

However, cases of violation of this law are still rampant, according to Traffic Operations 11 Officer Ulysses Empic and Traffic Aide Redosel Gabumpa. Similar reports are also noted in the Land Transportation Office.

Drivers of passenger vans in Cebu, however, are observed to maintain good practices when it comes to prohibiting children to ride in front seats as mandated by the Seatbelts Act of 1999.

This story has been produced with the help of a grant from The Global Road Safety Partnership (GRSP), a hosted project of the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC).