“I lost two children. They were shot dead. My family has never been the same.”

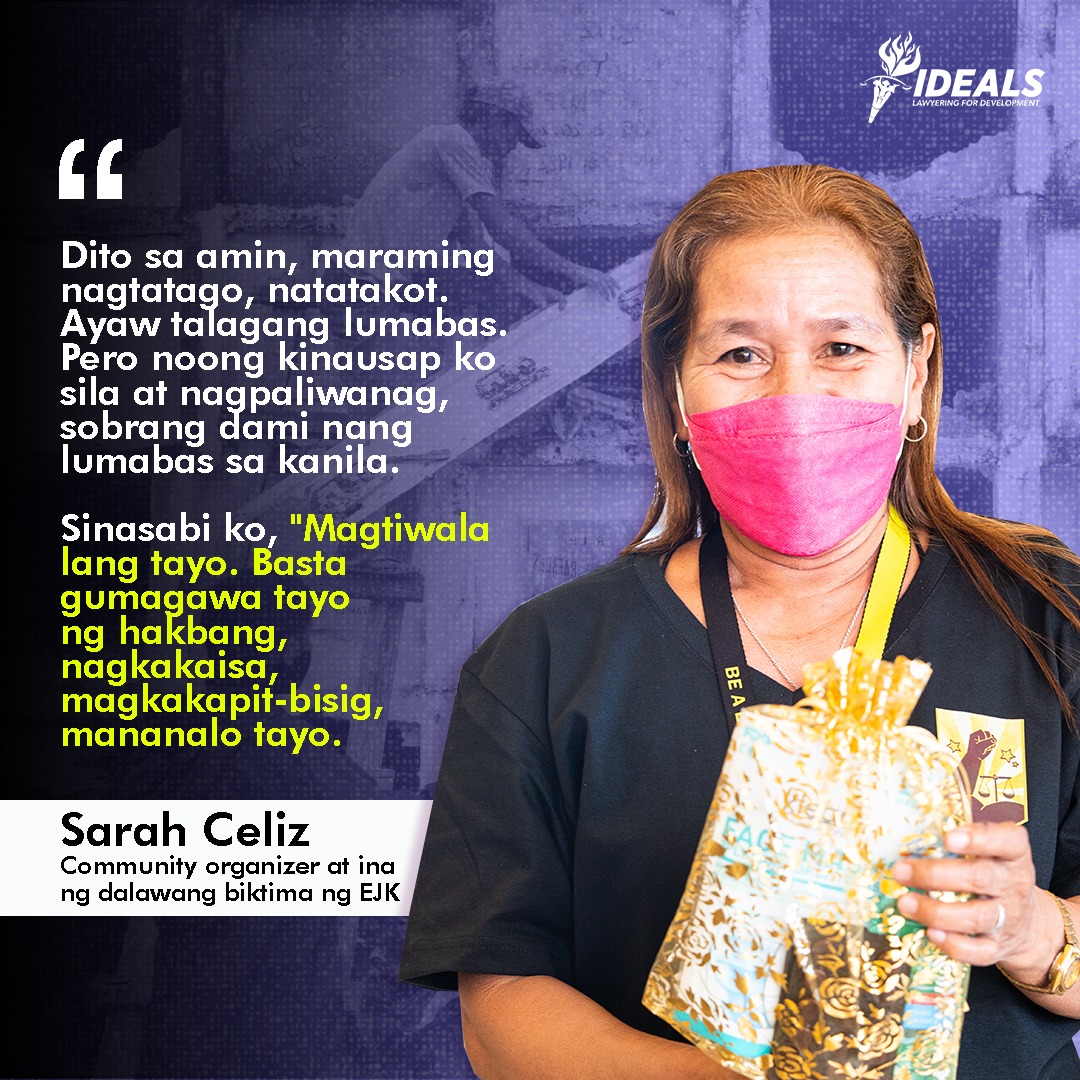

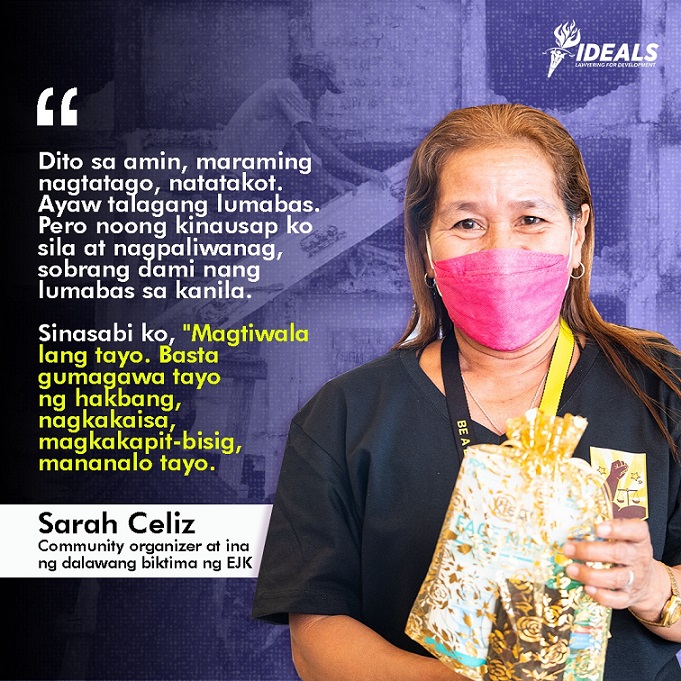

The story of Sarah Celiz, who lost her sons in extrajudicial killings (EJKs), resurfaced on the day the former president Rodrigo Duterte was arrested and detained at the International Criminal Court (ICC) in The Hague where he now awaits trial for crimes against humanity over his bloody anti-drug campaign.

Recalling how her sons, Almon and Dicklie, were gunned down six months apart in deadly crackdowns in their neighborhood in Bagong Silang, Caloocan City over seven years ago, Celiz broke down during a news conference.

When she tried to file a complaint, the police asked her for evidence.

“My evidence were the bodies of my sons. They were killed without due process,” Celiz declared.

“I want (Duterte’s) family to feel what we felt. I want them to feel the same way I feel about what happened to my sons,” she cried out.

Celiz and other family members of victims of drug war killings had kept vigil in shock and disbelief as they watched on TV and on their phones the arrest as Duterte was hauled off to a chartered plane by police escorts and flown out of the country he once ruled with an iron hand.

“I had tears of sadness because our loved ones are gone, and joy because Duterte is in the place where he belongs”, she said.

In the succeeding weeks, more families came out in the open, with tears of sadness and relief, to demand for accountability and justice for what they suffered during Duterte’s term from June 2016 to June 2022.

“My hope and that of the families of EJK victims is that we find justice so that we can move on with our lives,” Celiz said.

Firing up hope

Lawyer Ansheline Mae Bacudio said most EJK victims were breadwinners and household heads who left behind spouses, children, parents, siblings, and grandparents.. Their loss did not just hurt the bereaved families’ psych, it also hit them hard economically as many were forced to look for livelihood in order to survive.

“From 2016 onwards, we documented more than 700 cases of human rights violations that we submitted to agencies to help find justice, but the cases never progressed,” said Bacudio, who is human rights manager of IDEALS or Initiatives for Dialogue and Empowerment through Alternative Legal Services, an alternative lawyers’ group that assists the poor and marginalized.

She said Duterte’s arrest is a step towards justice as it renewed hope for the victims and their families. It would also pave the way for IDEALS to continue with the cases of the victims and survivors, whom they support under their Alyansa Para sa Karapatang Pantao (ALPAS) project.

“His arrest and detention is a message that no one is above the law,” she said. “This is just the beginning for justice.”

Never again

Duterte’s detention as he prepares for his confirmation of charges hearing in September has widened the doorway to the advocacy for a humane approach to drug use and dependence.

Lawyer Mary Catherine Alvarez, executive director of StreetLaw PH, an organization of Cebu City-based human rights lawyers, said her group will continue to work for policy reforms based on their experience working in communities.

StreetLaw PH works with and provides paralegal assistance and training to people who use drugs but have rights under the law on the understanding that “using drugs does not make people less worthy.”

“My position is that whatever happens next, we must maintain the importance of preventing more harm on people and of assuring that no one else has to die again as we work towards an approach that puts health and human rights first,” said Alvarez.

“It is important to prevent what happened from happening again,” she added.

The lawyer said the movement for drug policy reform needs to acknowledge the role of the existing policy, mainly Republic Act (RA) 9165 or the Dangerous Drugs Law, at the center of the large scale killings in the drug campaign.

Lessons from the Philippines

As the international community watched developments in the Philippines, the Global Commission on Drug Policy (GDCP) acknowledged the arrest of Duterte, saying that during his presidency, the “war on drugs led to thousands of deaths, with official reports citing over 6,200 fatalities in police operations, while human rights organizations estimate the toll to be significantly higher.”

“Many victims were from marginalized communities, deprived of due process, and their deaths have had enduring impacts on families and societal trust,” it said in a statement.

Based in Geneva, the GDCP consists of 28 commissioners, 15 former heads of state and prominent political, economic and cultural leaders who promote drug policies that prioritize public health, human rights, and social justice, and advocates for a drug policy that shifts from prohibition to human rights and evidence-based approaches.

The organization said the ICC’s action highlights the urgent need to transition from repressive drug policies to evidence-based, health-centered, and human rights-respecting approaches.

“Globally, the consequences of the ‘war on drugs’ have been severe: escalating incarceration rates, widespread human rights violations, and persistent public health crises,” it added. “We urge governments worldwide to reflect on the lessons from the Philippines and reject policies that prioritize punishment over progress. Drug policy reform is a matter of justice, public health and humanity.”

Gloria Lai, regional director for Asia of the International Drug Policy Consortium, a global network that works on rights-affirming drug policies with over 190 member organizations worldwide, appreciated the congressional investigations in the Philippines where Duterte admitted to his crimes prior to his ICC arrest and detention.

“In shedding more light on the acts of human rights violations, such as torture and extrajudicial killings, this would hopefully help sustain and expand the review of the devastating impacts of punitive drug policies that escalated terribly during the Duterte administration,” Lai said.

This was produced with assistance from the National Endowment for Democracy.