Filipino and American soldiers during a Balikatan military exercise, one of the activities covered by the Visiting Forces Agreement. Photo from U.S. Embassy in Manila.

“I would like to put on notice, if there’s an American agent here, that from now on, you want the Visiting Forces Agreement done? You have to pay.”

Thus, President Rodrigo Duterte laid down the country’s foreign policy.

Ironically, he did so after inspecting new air assets of the Philippine Air Force (PAF) donated by Washington in an event last February 12 at a former base of the United States in Pampanga, which is now the Clark Freeport and Special Economic Zone.

Vice President Leni Robredo and Senator Panfilo Lacson described the move as extortion, a charge dismissed by Presidential Spokesperson Harry Roque.In a press briefing three days after Duterte’s pronouncement, Roque even put a price tag on the deal: $16 billion. That’s the same amount that Pakistan receives as military aid from Washington for hosting and maintaining several U.S. military bases, he pointed out.

Duterte’s posturing is reminiscent of the bombast used by former strongman Ferdinand Marcos in dealing with the U.S. when it had bases in the country and was trying to draw the Philippines into the Vietnam war.

As it turned out, his nationalist bluster was only veneer for thievery.

On his birthday on September 11, 1966, with PAF jet fighters doing a fly-by over the Manila port area, Marcos sent off to Vietnam a contingent of the Philippine Civic Action Group (Philcag) composed of 1,000 engineers and medical workers as well as a small security force. Another 900 personnel would leave in the succeeding weeks.

This was a complete turnaround from Marcos’ campaign promise in the 1965 presidential election – that he would not allow the Philippines to be part of the U.S. war effort in Vietnam. Although Philcag was decidedly a non-combat troop whose main job was to go on public works and socio-civic missions in Tay Ninh province in southeast Vietnam, it was part of the effort to win the hearts and minds of the people for the U.S. and South Vietnam.

A U.S. Senate inquiry revealed three years later that Marcos changed his tune for a whopping $39 million.

But Marcos denied ever backtracking on his position.As recorded by Nick Joaquin (writing as Quijano de Manila) in Reportage on the Marcoses (1981), the former president said, “The allegation that this decision was imposed on me by the Americans is unfair, and it is not true. My decision was arrived at purely from a consideration of the national interest . . . I was asked whether any development in Vietnam had attracted my attention. I said yes, the massive support of America for South Vietnam. I was then asked what I, who had been quotedas opposing the sending of hostile troops to Vietnam, had to say about this latest development. I replied: ‘I am now ready to reassess my position; I am now in favor of sending additional aid to South Vietnam in the form of an engineering construction battalion with a security force.’ That was what the Vietnam government had requested—an engineering construction battalion—and I followed the request verbatim . . . I still maintain we are not sending hostile troops—though this may be a point of pure semantics!”

But this was not how many Filipinos saw it as noted by Condrado de Quiros in his column Dead Aim: How Marcos Ambushed Philippine Democracy (1997).He wrote: “But the nation did know a betrayal when it saw one and immediately erupted in protest over the Philcag. That, the Liberals chorused, was the kind of president the people had just voted into office. They warned of direr things to come. Meantime, the activists, who were just beginning to flex their muscles in the campuses, swept through the streets, launching a big demonstration before the American Embassy, a scene that would be repeated more and more frequently in years to come. The rally ended on a bloody note, riot police charging through the ralliers with teargas and truncheon. That, too, would be repeated more and more frequently in years to come.”

By 1967, Philcag’s presence in Vietnam remained controversial. To sustain its operations, the troops needed P38 million but Marcos failed to include a bill financing Philcag among the 31 urgent measures he sent to Congress for approval both in 1967 — and the following year. Philcag started to run out of funds by March 1968, forcing Marcos to reduce the Philcag contingent which by then was drawing funds only from the savings of the defense department.

Two years later, Marcos and Congress agreed to just bring Philcag back to the country. “Funds being spent for Philcag would be better utilized for pressing economic development projects in the Philippines,” a report by the United Press International (UPI) quoted a member of Congress as saying.

In October of that same year, the Senate Subcommittee on US Security Agreements and Commitments Abroad chaired by Senator Stuart Symington began hearings on military aid in the Vietnam War which also looked into funding for Philcag.

Writing on the findings of the Symington subcommittee in a December 10, 1969 article headlined “U.S. ‘Bought’ Marcos Army,” Ward Just of the Washington Post said,

“It is an extraordinary document, mixed with wonderful ironies and absurdities all of which combine to throw the United States into a lover’s embrace with a country whose people probably don’t want us around at all, and a government whose principal preoccupation is cash.”

He further noted, “What emerges from this hearing is that the United States is paying for the Philippines for the privilege of defending it against attack. Apart from the $38 million for Philcag, there is $22.5 million a year for military assistance, and beyond that . . . there are 20 American stations in the Philippines, which pump an estimated $150 million a year into the economy.”

Just also quoted Sen. James William Fulbright as saying, “My own feeling is that all we did was go out and hire soldiers in order to support our then-administration’s view that so many people were in sympathy with our war in Vietnam, and we paid a very high price for it.”

The Marcos administration was swift and firm in its denial. Malacanang released a statement saying that it was “erroneous” to describe Washington’s contributions to Philcag as a “subsidy in any form or as a fee.” It stressed that “Philcag received direct exclusive funding from the Philippine government and from no other source.”

Succeeding investigations by the U.S. General Accounting Office and the Philippine senate would belie this. Research have exposed how Marcos squeezed Washington for millions of dollars in the name of the Philcag team in Vietnam. It is uncertain if those funds ever reached the Philcag personnel, but there is confirmation that a significant portion of it went to Marcos’s pocket.

In April 1972, for example, a Philippine senate committee headed by Sen. Leonardo Perez confirmed what the Symington subcommittee already made public. As reported by UPI: “The committee said in a 37-page report that the Philcag received $19.6 million from the U.S. government. It also said former Defense Secretary Ernesto Mata got $3.6 million from the (U.S.) under the military assistance program.”

American author Raymond Bonner recounted in his book Waltzing with a Dictator: The Marcoses and the Making of American Policy (1987) a more damning story on how Marcos received his cut. “At least $39 million was spent by the United States to equip, train, and pay (Philcag). . . throughout Marcos’s first term—the U.S. embassy had been delivering quarterly checks, each in the amount of several hundred thousand dollars.”

According to Bonner, a diplomat at the U.S. Embassy in Manila from June 1966 to September 1973 James Rafferty was responsible for personally bringing some of the checks to Marcos. The author noted that U.S. intelligence, military, and diplomatic officials in the Philippines at the time had no doubt that much of this amount went into the strongman’s pockets or more accurately, into his overseas bank accounts.”

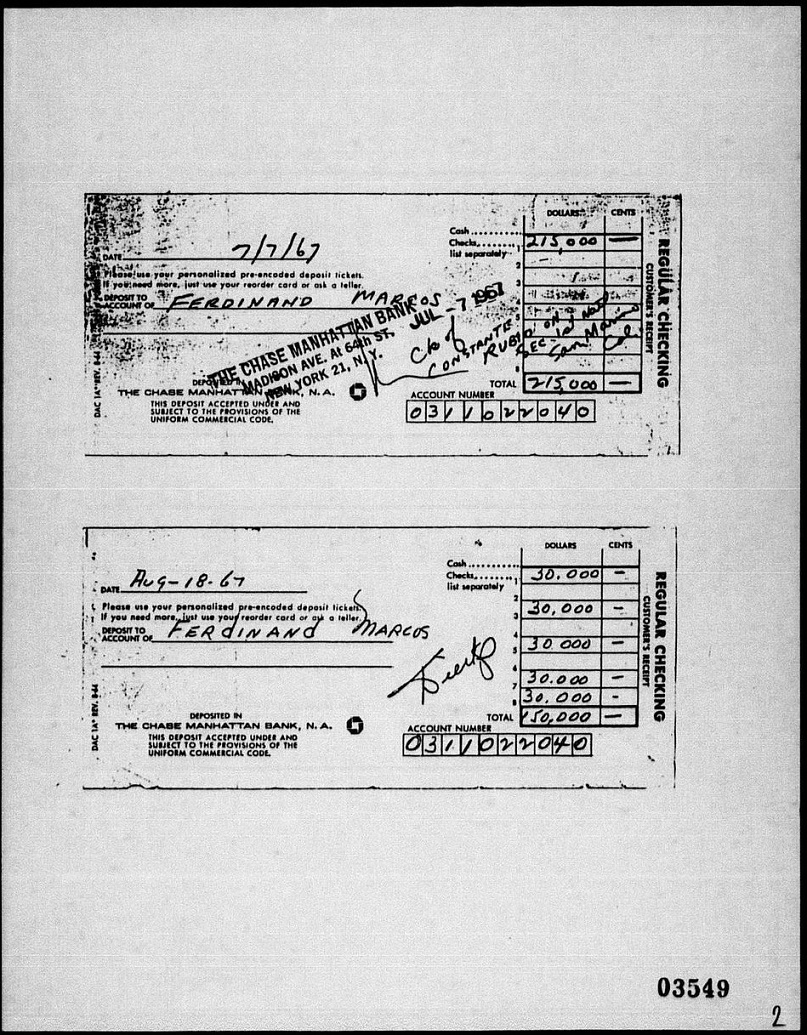

It is well-established that Marcos and his wife, Imelda, opened bank accounts in Switzerland in 1968 under their pseudonyms William Saunders and Jane Ryan. A lesser-known fact is that among the papers with the Presidential Commission on Good Government are photocopies of two deposit slips of a Chase Manhattan account of Marcos: one dated July 7, 1967 was for $215,000 and another for five checks worth $30,000 each on August 18, 1967.

A Chase Manhattan check for Ferdinand Marcos. Photo from PCGG records.

Bonner’s claim is bolstered by David Chaikin and J.C. Sharman in Corruption and Money Laundering: A Symbiotic Relationship (2009), revealing that a General Accounting Office investigation could not trace how U.S. funding for Philcag was spent and several senior U.S. officials suspected that Marcos had diverted the funds for his “own personal political advantage.”

The authors cited a statement by a former U.S. ambassador to the Philippines that Marcos had not “felt under any obligation to use the funds . . . for the Philcag directly, but had actually used it for purposes, such as ‘security matters.’”

Given their classified nature, Marcos was unwilling to disclose how he utilized the Philcag funds—even to the Americans.

According to author Alfred W. McCoy, the former strongman “manipulated” his alliance with Washington to win more resources for the military. In Closer than Brothers: Manhood at the Philippine Military Academy (1999), McCoy wrote,“Aside from equipment for other AFP units, Marcos also demanded, during the three years (Philcag) served in Vietnam, ‘special payments’ of a million dollars per year—delivered directly to his office by the U.S. Embassy. These negotiable checks, never audited, may have provided Marcos with the black funds for covert units within the AFP.”

Fast forward to present day.

Duterte has not made public his statement of assets, liabilities, and net worth since 2018. This reticence in disclosing his accumulated wealth given the decades the President has been in public office does not inspire confidence that the “payment” he now demands from the U.S. will not go the way “aid” from Washington did during the Marcos regime.

Alternatively, Duterte’s bluster can also be read as a way to save face given his near-amorous relationship with China.

So, with one hand Duterte receives goodies from the Americans and with his other hand, slaps the U.S. with VFA issues and demands to show his possibly jealous Chinese mistress that the deal is not part of any deep romantic entanglement. If we follow Duterte’s logic, future trysts with the Americans could include payment upfront and not just a roll of bills left on the side of the bed after the deed is done.

(Joel F. Ariate Jr. is a university researcher at the Third World Studies Center, College of Social Sciences and Philosophy, University of the Philippines Diliman. This piece is part of the Center’s on-going research program, the Marcos Regime Research. Miguel Paolo P. Reyes provided research assistance.)