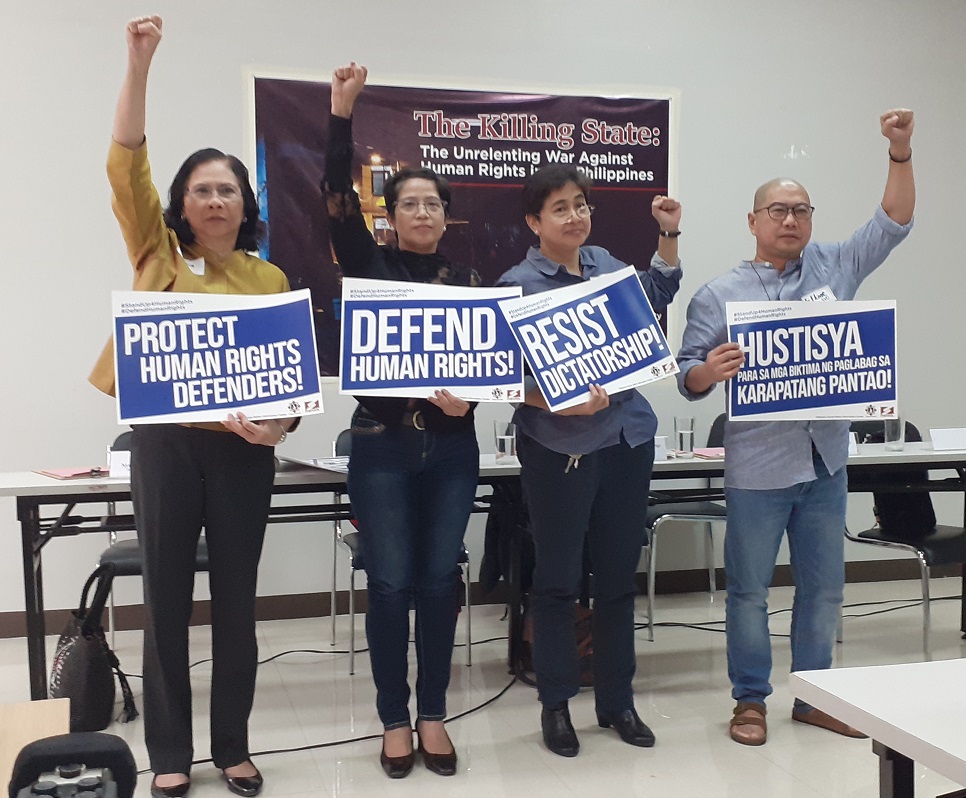

“Duterte’s drug war is war against human rights.” (L-R) Philippine Human Rights Information Centre Executive Director, Dr. Nymia Pimentel-Simbulan, KILUSAN para sa Pambansang Demokrasya Secretaty-General, Atty. Virginia Lacsa-Suarez, Rev. Fr. Flaviano Antonio Villanueva, UP Manila Department of Pathology Chair, Dr. Raquel Rosario-Fortun

President Rodrigo Duterte’s bloody drug war, which the Commission on Human Rights claims to have resulted in 27,000 deaths, has escalated to “an unrelenting war against human rights,” with evidence showing that the killings are “systemic, coordinated, sequential, and comprehensive,” the Philippine Human Rights Information Center (PhilRights) said.

In its report, “The Killing State: An Unrelenting War Against Human Rights in the Philippines,” PhilRights said there is enough evidence to conclude that the drug war “has resulted in gross and interrelated human rights violations that extended to the families and communities of those who have been killed.”

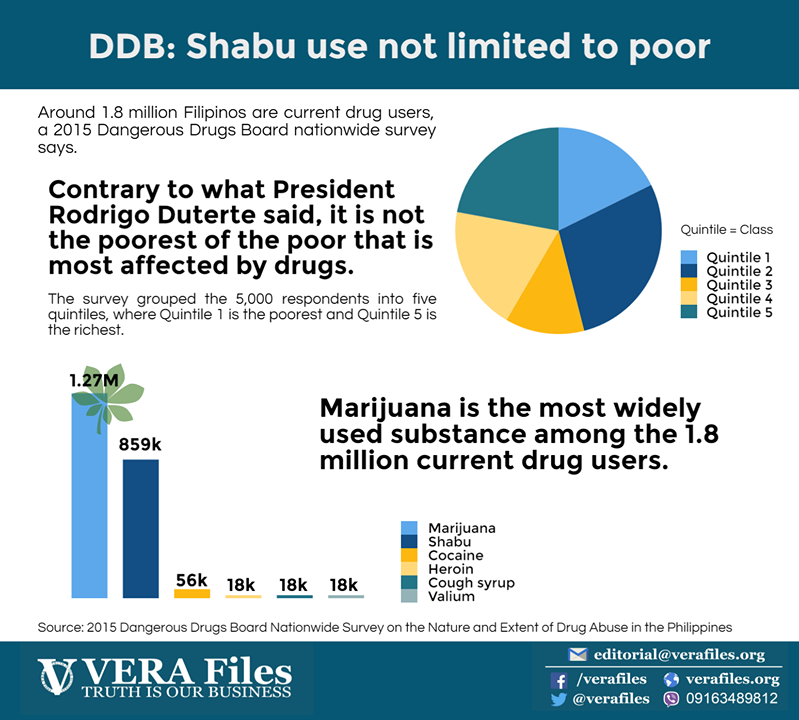

The group documented 118 alleged extrajudicial killings (EJK) victims in Metro Manila, Bulacan, and Rizal, since Duterte took office in July 2016 up to present. Based on their study, the victims are “mostly male adults within the productive age range (18-35 years old), are family breadwinners, are low- and irregular-wage earners from the informal sectors, are of low educational attainment, and are residents of urban poor communities.”

Three out of five of the documented victims had links to illegal drugs, while two out of five had no known links to illegal drugs and were believed to be killed because of schemes such as “palit-ulo” or are victims of mistaken identity, or were killed in operations targeting other persons, the study showed.

The peaks of documented killings were on August 2016, August 2017, and July 2018, or immediately after the president’s State of the Nation Address (SONA), where he renews his orders to put an end to the illegal drug trade in the country.

In his SONA last year, Duterte vowed that the “illegal drugs war will not be sidelined…it will be as relentless and chilling, if you will, as on the day it began.”

The government figure on death related to the drug war is 6,000.

Other striking patterns and modalities showed in the study:

- Over half or 52 percent of the killings were done during police operations and under police custody; 13 percent were done in operations believed to be conducted by the police as alleged by informants; and 35 percent were killed by unidentified assailants and riding-in-tandem killers;

- All documented victims bore gunshot wounds; one in five victims bore signs of torture, including beatings, dismembered body parts, broken limbs, missing fingernails, and burn marks;

- Over half or 53 percent of all documented victims bore three or more gunshot wounds; one out of five victims sustained head and neck bullet wounds;

- One in five victims had been visited by an Oplan Tokhang team prior to being killed;

- Alleged violations occurred before and after the killing for some of the victims, including torture, illegal arrest and detention, illegal searches and ransacking, harassment and threats, loss or destruction of personal properties, and denial of medical care;

- Alleged tampering of evidence, including the intervention of funeral personnel immediately after the killing and the taking of already dead victims to hospitals were also reported by informants; and

- Families of about three in five documented victims had difficulties in accessing documents, especially police and medico-legal reports.

The report also showed multidimensional impact of EJKs including informants and affected communities’ “perceived sense of insecurity in their homes, and in general, in the communities where most of the killings are happening,” compromising their freedom of movement.

“The brutality of killings have sent shockwaves that reverberate across sectors and geographies. Many victims and families have been kept silent, by choice or by desperate circumstances,” PhilRights Executive Director Nymia Pimentel-Simbulan said.

Other impact of EJKs on informants and affected families according to the study:

- Informants believe that the families’ violation of rights due to inability to seek and attain justice through the legal system should be recognized as a violation of rights;

- Families are compelled to hide the fact that their family members were victims of alleged EJK in order to gain access to support services from government agencies and private institutions;

- The killings have direct and adverse effect on the physical and psychological health of family members, including weight loss, loss of appetite, paranoia, and insomnia, among others;

- Children and other family members, especially those who witnessed the killings, have shown signs of psychosocial effects, including anger, violence, aggressive tendencies, and social withdrawal;

- Some children needed to quit school due to financial difficulties, whereas some had to stop attending classes due to the stigma associated with being children of alleged EJK victims; and

- Informants perceive a loss of the sense of solidarity, unity, and harmony among families and communities, a sense of isolation in relation to quality of daily interaction with neighbors and the feeling of being betrayed by barangay officials.

“Deaths and killings are simply achievements for this administration and this shows the distorted moral of the administration of Duterte. The war on drugs has actually expanded and has become a war on human rights, dahil pinapakita dito na pag pinatay ang isang tao (because it only shows that when you kill somebody)…ang buong pamilya niya ay maapektuhan, ang karapatang pantao ng pamilya niya ay maaapektuhan (the victim’s family will be affected, the family’s human rights will be affected),” said lawyer Virginia Lacsa-Suarez, secretary-general of KILUSAN para sa Pambansang Demokrasya.

“The war on drugs can now be called as war against human rights, against the masses, against human rights defenders, wala nang sinisino (no one is spared),” Suarez added.

Aside from the alleged EJKs, PhilRights also documented 45 cases of other violations such as frustrated EJKs, illegal arrests and arbitrary detention, and enforced disappearances.