Nearly 17 years after the Philippines became a party to the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC), the first international treaty negotiated under the auspices of the World Health Organization (WHO), efforts to comply with some of the remaining major commitments are met with even more intensified resistance from the legislature.

In its periodic reports to the Conference of Parties (COP), the governing body of the WHO-FCTC, the government has always identified “political environment” as the constraint or barrier encountered in implementing the convention.

In recent months, legislators perceived as advocates of the tobacco industry have been discrediting the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), and seeking to nullify an issuance restricting interaction with the tobacco industry.

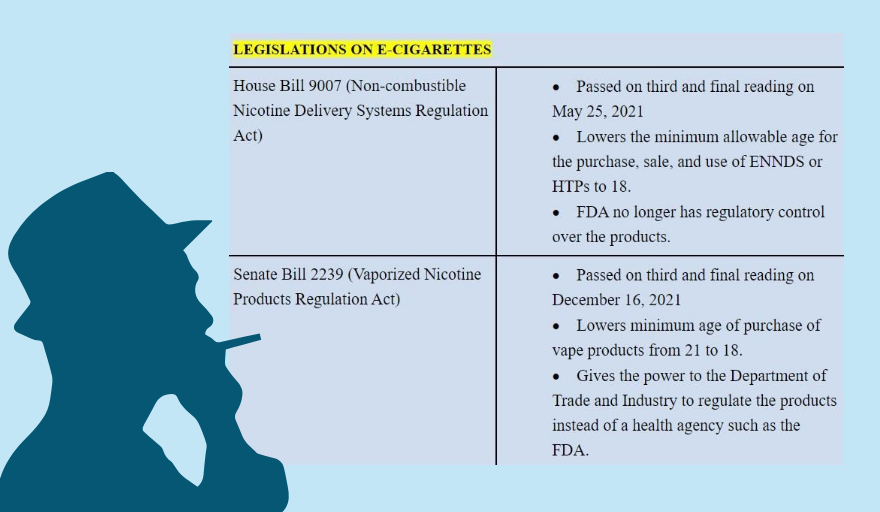

These moves are seen as part of an increasing resistance to measures meant to insulate the government from tobacco industry influence. They are parallel to efforts in Congress to reverse strict regulatory policies laid down in Republic Act No. 11467, enacted in January 2020, and Executive Order No. 106, issued a month later, on the use, sale, manufacture, importation and distribution of electronic cigarettes or vapes and heated tobacco products (HTPs) to protect public health.

The government considered the enactment of RA 11467 as “an advancement in tobacco product regulation,” as it reinforces the regulatory authority of FDA over electronic nicotine delivery systems (ENDS), electronic non-nicotine delivery systems (ENNDS) and HTPs. However, the pending legislation threatens to reverse the law shortly before its scheduled full implementation by May.

One of the most challenging commitments in the FCTC is Article 5.3, which calls for protection of the country’s tobacco control and public health policies from commercial and other vested interests of the tobacco industry, says Rodley Carza, head of the Department of Health’s (DOH) Policy and Technology Division under the Health Promotions Service.

“A lot of articles in the FCTC can be managed through purely administrative and legislative work, or scientific, but [insulating the government from] tobacco industry interference will take a lot of political will and adherence to a certain principle is really out of the control of the [DOH],” Carza explains in an interview with VERA Files.

In the course of justifying a legislative action to transfer regulatory authority over e-cigarettes or vapes and HTPs from the FDA to the Department of Trade and Industry (DTI), the House committee on good government and public accountability investigated the FDA for receiving a grant of $150, 430 (around P7.5 million) in 2016 from foreign entities known for their anti-tobacco advocacies, namely, The Union Against Tuberculosis and Lung Diseases (The Union) headquartered in Paris, France; and Bloomberg Philanthropies (Bloomberg), based in New York City.

Rep. Jericho Nograles of Puwersa ng Bayaning Atleta party list even raised the issue of sovereignty. “The bigger issue here is do we allow government agencies to be influenced by monies coming from foreign private organizations?” he asked, adding the grant was an “attack on our independence” and is unconstitutional.

“Why are you waging a war against a legitimate industry?” Deputy Speaker Rufus Rodriguez of Cagayan de Oro asked FDA officials during the inquiry. The industry provides livelihood to thousands of farmers, generates jobs, and pays taxes, he added.

Deputy Speaker Rodante Marcoleta of SAGIP party list butted in, saying the tobacco industry “needs to be protected also.”

Deputy Speaker Deogracias Victor Savellano, from the tobacco-producing province of Ilocos Sur, said the foreign funders may have influenced the FDA when it formulated the guidelines on the use of e-cigarettes and HTPs, thereby undermining the country’s sovereignty.

Dr. Rolando Enrique “Eric” Domingo, then-director general of FDA, explains the grant was for a project called “Strengthening the Regulatory Systems of Tobacco Control under the Food and Drug Administration.” The project needed to hire additional staff to implement the agency’s mandate to regulate ENDS/ENNDS, HTPs and vapor products under RA 11467.

Speaking to VERA Files, Domingo asserts the grant was above board. He says FDA followed all of CSC’s rules on such grants, ensuring there was no conflict of interest among the DOH-FDA and their partners, who are all health advocates.

Domingo believes, however, that efforts to weaken the FDA is a “legal maneuver” the global tobacco industry employs not only in the Philippines but in other countries as well.

In 2014, the DOH issued Administrative Order No. 2014-000816 covering ENDS/ENNDS, classifying them as pharmaceutical products to be regulated by the FDA. Under RA 11467, these novel tobacco products fall under the FDA’s regulatory functions.

The congressional probe began two months before pro-tobacco legislators approved in May 2021 House Bill No. 9007, which reclassifies ENDS/ENNDS as consumer products and consequently transfers regulatory functions over them from the FDA to the DTI, thus rendering the grant spending for naught.

Domingo quit his post in January 2022, weeks after the humiliating interrogation by lawmakers, some of whom insinuated FDA officials pocketed part of the grant.

The FDA reported to the House that it used P3.5 million of the grant to hire staff, and P1.6 million unused amount was returned to The Union. The rest was spent buying reagents and setting up the Information Technology system.

Despite the FDA’s explanations, criticisms questioning the agency’s credibility went on.

“You know, the fight against tobacco is really tiring,” Domingo says. “The attacks keep coming, from all sides, and your allies seem to be so few.”

While the DOH and FDA are allies, it is difficult to find supporters from other sectors, even within government, he says. “It’s one of the things that makes me tired,” Domingo adds, three weeks after leaving his post as FDA chief.

It is clear to him who are the forces behind the moves to emasculate the FDA. “I would think the only people who would gain from this are from the tobacco industry and, of course, people engaged in the business of vapes and HTPs.”

“Health systems all over the world keep feeling the pressure,” he adds. “In fact, under FCTC, the WHO has always been working against the influence of the tobacco industry when it comes to policy setting, and you just have to be steadfast and you just have to really know what your goals are.”

For the FDA, Domingo says: “It’s really just public health. There’s nothing unclear about it. The DOH and FDA will always work for public health, and that also means working always against the use of tobacco. Tobacco has no healthy use in any way.”

Conflicting interests

While the pro-tobacco lawmakers raised ethical questions and conflict of interest issues against the FDA over the grant, they were silent on sponsored exposure trips to tobacco industry’s facilities in Europe. Like the pot calling the kettle black, some of them were on those trips.

The lawmakers, specifically Deputy Speakers Rodriguez, Savellano and Marcoleta, and Reps. Estrellita Suansing of Nueva Ecija, Sharon Garin of AAMBIS-OWA party list, Alfredo Garbin Jr. of AKO-Bicol party list, and Nograles took turns interrogating FDA officials on the propriety and constitutionality of receiving the grant from The Union and Bloomberg.

On the other hand, they were vocal against the restrictions for “unnecessary interactions with the tobacco industry” under the CSC and DOH’s Joint Memorandum Circular 2010-001. In fact, they moved that the issuance be declared void ab initio (from the beginning), saying Health Secretary Francisco Duque III— the CSC chairman at that time who signed the JMC with then-secretary Esperanza Cabral of the DOH— did not have authority from the other commissioners to issue it.

JMC 2010-001, intended to protect the bureaucracy against tobacco industry interference, prohibits the following:

· Unnecessary interaction with the tobacco industry, except “when strictly necessary” for effective regulation, supervision and control and full transparency is required in any dealing to avoid perception of real or potential partnership or cooperation resulting from such interaction

· Preferential treatment to the tobacco industry in terms of providing incentives, privileges or exemptions not provided for by law

· Accepting gifts, donations and sponsorships including gratuity favors, entertainment, loan or anything of monetary value in the course of official duties

· Financial interest in the tobacco industry

· Accepting other favors comparable to those mentioned above, like employment or recommending a family member for hiring in any private enterprise connected with the tobacco industry which has regular or pending official transaction with the agency

· Conflict of interest with the tobacco industry

· Engaging in an occupational activity within the tobacco industry within a period of time after leaving government service.

The prohibitions cover all government officials and employees, regardless of status, in the national and local government, including government owned and controlled corporations and state colleges and universities.

The JMC defines tobacco industry interference as the broad array of tactics and strategies used by the industry to interfere with the setting and implementing of tobacco control measures.

Carza, whose office monitors, implements and develop policies on tobacco control pursuant to the WHO FCTC, says lawmakers’ moves to nullify JMC 2010-001 clearly manifest the tobacco industry’s interference in policy making.

“It’s something that we need to abide by because it’s a commitment of the country to the FCTC. As long as you’re in the government, whether appointed or elected, we are covered by this policy, but again there are attempts to weaken this policy, so it’s really important for us to have a stronger policy statement on this,” he says.

Asked if legislators are covered by an issuance from the executive branch, Carza says: “Insofar as the DOH is concerned, the JMC covers the entire government, the entire bureaucracy–whether you’re elected or appointed. In the JMC, the operative term used is public official; no distinction whether appointed or elected.”

Carza acknowledges policy gaps and inconsistencies in the country’s compliance to the requirements under the FCTC. One of these is the lack of awareness among public officials and employees on the restrictions provided in JMC 2010-001.

Violation of any of the prohibitions under JMC 2010-001 is considered a ground for administrative disciplinary action under Executive Order No. 292, or the Administrative Code of 1987. It may also constitute criminal and civil actions under existing laws.

Almost 12 years since the circular came into force, no one has filed a complaint to the CSC despite apparent violations like receiving donations from the tobacco industry, going on exposure trips to the industry’s facilities, and openly defending the industry in congressional hearings.

To Rep. Rozzano Rufino Biazon of Muntinlupa City, JMC 2010-001 is necessary for policy formation to be insulated from tobacco industry influence.

“This industry knows that these efforts to safeguard health is a threat to their industry’s health, so there’s a conflict of interest there — the interest of the tobacco industry to earn profits and the interest of the government to protect the people’s health,” he points out.

“It involves a product that has already been proven by science to be detrimental to the health of people and, definitely, to address that threat to the industry, they’ll spend to ensure their industry’s profits and the foremost strategy is to influence policy.”

Biazon authored a bill seeking to regulate ENDS/ENNDS but had to later withdraw his name from a list of sponsors when the consolidated version of similar bills turned out to be an “economics-driven regulatory law instead of being purely health protection law.”

During the ninth session of the Conference of Parties (COP9) to the WHO FCTC in November 2021, the Philippines was given three “Dirty Ashtray” awards—a lampoon prize for companies and governments seen as peddlers of tobacco industry interests—by the international watchdog Framework Convention Alliance (FCA), a Geneva-based confederation of 350 organizations pushing for FCTC’s implementation in signatory countries.

Medical associations and health advocates said the shameful “Dirty Ashtray” awards are “proof of the strong and rising tobacco industry interference in the Philippine government” and that “tobacco interests are front and center” in the delegation’s agenda while public health interests take a backseat.

The only time the Philippines received the “Orchid” award was in 2012 for excluding the National Tobacco Administration from the official delegation to the COP5 in South Korea. The award, the opposite of the “Dirty Ashtray,” is given to parties who stood their ground to support the global health forum’s agenda.

In 2010, the Philippines also got the “Dirty Ashtray” award after the country’s delegation mouthed pro-tobacco industry interests at the COP4 in Uruguay. The same thing happened last year when the delegation led by Foreign Secretary Teodoro Locsin Jr. praised the tobacco industry not only as a “source of good through taxation” but also for creating “products that delivered a similar satisfaction, but with far less harm.”

At the end of the five-day conference in Geneva, the Philippines got the most number of “Dirty Ashtray” awards from the FCA: for insisting on amendments “with unhelpful and often confusing wording,” for attempting to block progress at the COP at the 11th hour, and for using the COVID-19 management burden to “ignore” the FCTC despite “links between tobacco, non-communicable diseases, and COVID-19.”

Health experts say that tobacco use increases the risk of suffering from serious symptoms due to COVID-19.

*VERA Files reached out to PMFTC, Inc., the Philippine affiliate of Philip Morris International, for its side of the story. The company, which controls over 90% of the local market, declined our requests for an interview and a comment to a set of questions “until [the vape bill is] officially acted upon by the Palace.”

This story is part of the project Seeing Through the Smoke, which is supported by a grant from the International Union of Tuberculosis and Lung Disease (The Union) on behalf of STOP, a global tobacco industry watchdog.