SARAJEVO – Fact-checkers had been called names: censors, foreign agents, enemies of the state and presstitutes, probably the worst term that allies of former president Rodrigo Duterte have referred to journalists in general and fact-checkers in particular.

But don’t those words better describe the same people who coined them?

Fact-checkers been subject to various forms of harassment such as verbal abuse, coordinated attacks, legal threats, political pressures and even physical violence.

For three days last week, around 500 fact-checkers representing 180 organizations in 80 countries across the globe gathered in this capital of Bosnia and Herzegovina for the 11th Global Fact-Checking Summit (GlobalFact 11). It is an annual conference organized by Poynter’s International Fact-Checking Network (IFCN). This year, the gathering was coordinated with local partner ZestoNe.

There was a lot of sharing of information, experiences and strategies in the fight against mis- and disinformation, and networking.

From the plenary discussions, workshops and breakout sessions, it would appear that fact-checkers have been dealing with almost the same problems, particularly those in countries with restricted or threatened democracies where governments try to discredit people who call them out and demand transparency and accountability for creating, peddling and spreading mis- and disinformation.

Steven Levitsky, wearing his hat as a political scientist, professor at Harvard University and co-author of “How Democracies Die” and “Tyranny of the Majority,” said in his closing remarks that populist candidates are now winning elections much more frequently than at any other time in history because political establishments, such as political parties, interest groups and big traditional media organizations are weakening.

“Collectively, political establishments do tend to impose certain parameters on politics, both in terms of political style and in terms of policy substance,” Levitsky said.

Sitting down later with IFCN Director Anglie Drobnic Holan in an interview session, the Harvard professor said the weakening of political establishments is “unquestionably” democratized as it opens up the political system to a wider array of people. However, it also means that democratic institutions are left vulnerable to anti-system forces.

However, he said, “The world is still considerably more democratic than it was in the 1990s despite the rise of China, despite (Russian President Vladimir) Putin, despite Trump, despite social media, despite AI, despite COVID.”

“To me, that suggests a fair amount of democratic resilience,” he said, noting that many new autocracies often inherit weak states and thus fail to deliver public services to their citizens.

He emphasized the critical role of the opposition and independent media for democracies to flourish, saying that “without an independent, self-sustaining media, it is impossible to guarantee citizens the information they need to oppose the government.”

“Democracy absolutely requires opposition. If there’s one thing that sustains democracy, it’s opposition, and sustainable opposition requires two things: It requires autonomous citizens, and it requires an independent private sector,” he said.

In some breakout sessions, tech companies such as Meta, YouTube and TikTok took a heavy beating from speakers and participants, taking them to account for allowing the spread of mis- and disinformation through their social media platforms, contributing to the erosion of democracy in some countries.

At one point in her keynote remarks on Wednesday, the Philippines’ Maria Ressa, founder and chief executive officer of Rappler, called Meta founder Mark Zuckerberg as “the bigger dictator” than former president Rodrigo Duterte, “part of it is because he’s not an elected official.”

“What you’re seeing on social media is a mob, and a mob creates a chilling effect. A mob changes reality,” she pointed out. She said Meta’s business model shifted when it “commoditized the people and the content.”

While thanking the tech companies for funding fact-checking, Ressa also called on them “to literally do something right now to protect democracy, to prevent genocide.”

“We’re frenemies,” she said.

Other fact-checkers who spoke on stage, with a large screen bearing the tech companies’ names as sponsors for the event, also criticized them for doing little to stop the flow of mis- and disinformation in their social media platforms, and somehow even encouraging creators and peddlers by monetizing content, including scams hoaxes and misleading or deceptive advertising.

Fact-checkers raised concern that as they struggle to do their jobs effectively under a barrage of falsehoods and harassment, the continuing spread of false information on social media can jeopardize elections and influence public policy.

On TikTok’s policy of removing misinformation instead of providing additional information and context, fact-checkers said this raises freedom of speech issues, adding that providing users additional context is more effective at fighting and preventing misinformation than removing the offending content completely.

GlobalFact 11 came out with a Sarajevo Statement, declaring that fact-checking adds to public debates and should never be considered a form of censorship, at the same time reaffirming that fact-checking is an act of free expression that seeks to give the public accurate information and improve information ecosystem.

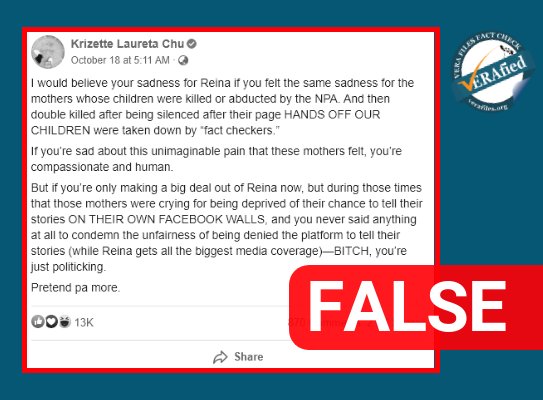

It seeks to address growing concerns over escalating attacks on fact-checkers, including labeling them as enemies of the state, foreign agents, or, in the case of the Philippines, presstitutes. All over the world, fact-checkers have faced increasing hostility, including online threats, court suits and various forms of harassment.

“All the people have the right to seek, receive and impart information and ideas. Fact-checking is deeply rooted in these principles. Fact-checking requires the right and ability to find sources, read widely and interview experts who are free to speak candidly- all as part of rigorous methodology and process. This is the foundation on which all true fact-checking is built. Fact-checking is part of a free press and high-quality journalism, and it contributes to public information and knowledge,” part of the statement reads.

“Fact-checking seeks to provide additional information, setting out evidence to correct and clarify messages that are false, misleading or lack important context. Fact-checking does not seek to expunge or erase these messages, but to preserve them as part of the public debate while offering evidence necessary to accurately inform that debate,” it further says to explain the work of fact-checkers.

The views in this column are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of VERA Files.

This column also appeared in The Manila Times.