John Tobit Cruz, a councilor in Taytay, Rizal, is used to receiving constituents who seek his help to pay for their medicine or hospital bills. But he began to notice something different.

Parents are now also asking for assistance to cope with the chronic illnesses of their children — 12 years or younger — who were living with cancer, heart disease, kidney disease requiring dialysis, and type 2 diabetes.

“We received 50 requests from parents of kids with these diseases in December 2023, more than double the 20 requests that we got in November,” Cruz said in an interview.

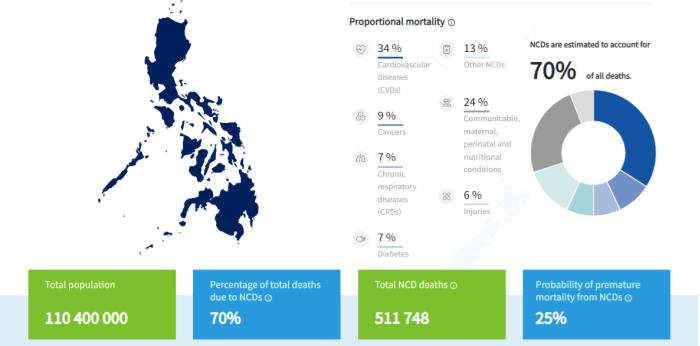

These chronic illnesses — long-term health conditions that shorten lifespans and affect quality of life — are typically associated with adults. These illnesses, also called non-communicable diseases (NCDs), are the top causes of death in the Philippines; 70% of deaths in the country are due to these illnesses. One in every 4 people in the Philippines will likely die of an NCD before he or she turns 70 years old, according to World Health Organization (WHO).

NCDs are also a major public health concern among younger people and children. Worrisome proportions within this group are affected by overweight and obesity and thus at greater risk of developing chronic illnesses of the type Cruz was hearing parents tell him about.

Nutrition officers in barangays in Taytay have already noticed “many chubby children in schools,” said Cruz. “Their weight may already negatively affect their health.”

Worrisome trends

In a fact sheet, the WHO defines overweight and obesity as follows for children aged between five and 19 years:

- overweight is body mass index (BMI)-for-age greater than one standard deviation above the WHO Growth Reference median; and

- obesity is greater than two standard deviations above the WHO Growth Reference median.

Taytay’s municipal nutrition action office uses the above definitions in reporting the status of students in public schools. Data from the office shows that among 23,040 students weighed in eight high schools, 5.42% (1,249) were affected by overweight and 1.91% (439) had obesity during school year 2022-2023.

Among 40,221 students weighed in 17 elementary schools, 5.47% (1,860) were affected by overweight and 2.34% (697) had obesity during the same school year.

These percentages may seem low. But for Taytay’s local government officials, the trends are worrying enough, given the national statistics for childhood and teen overweight/obesity in the Philippines.

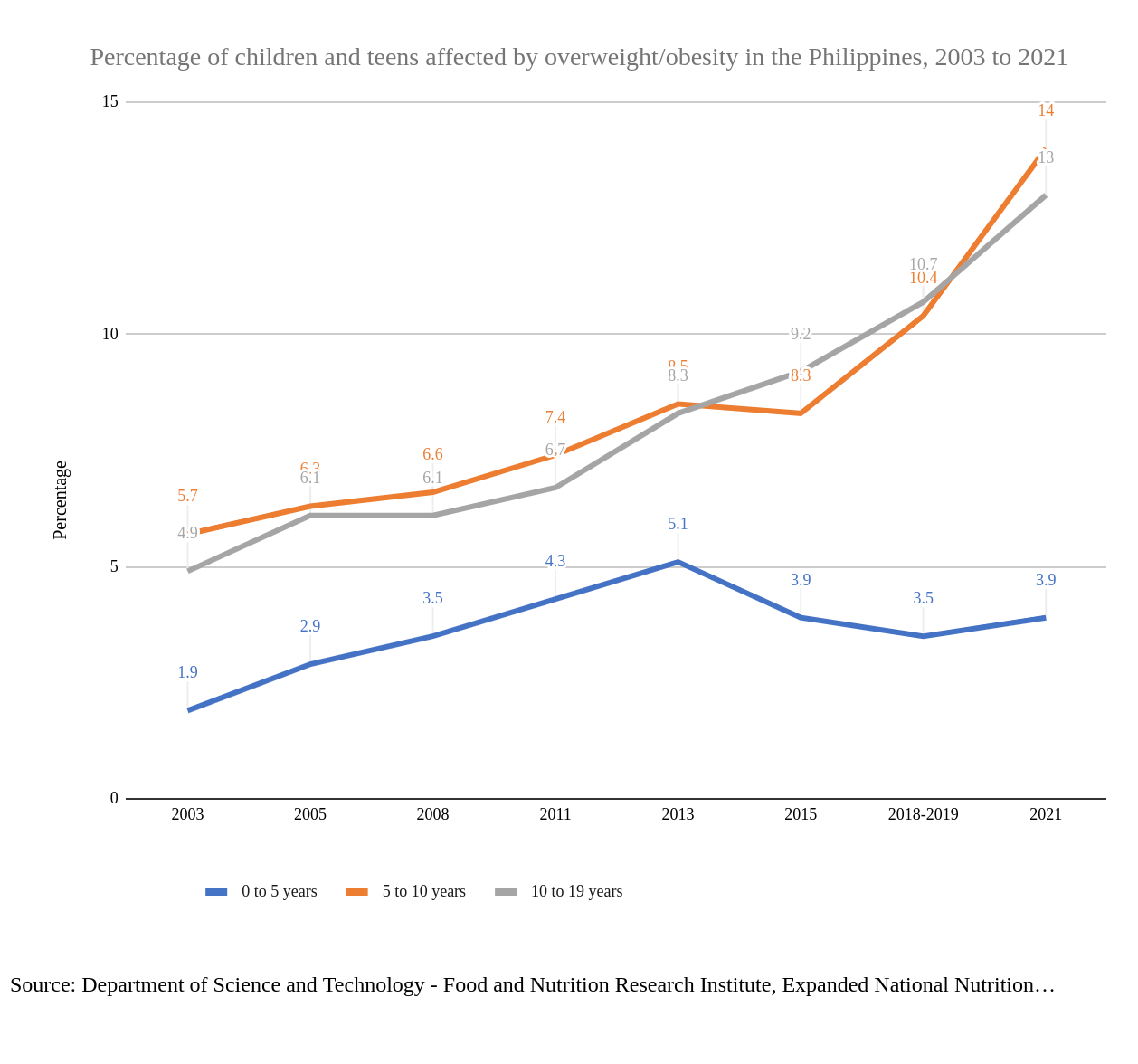

The Department of Science and Technology (DOST) – Food and Nutrition Research Institute (FNRI) uses one statistic to count children and teens aged five to 19 with overweight/obesity, which it defines as BMI-for-age greater than one standard deviation above the WHO Growth Reference median. The current proportion of children and teens aged five to 19 who are affected by overweight/obesity is about 13.5%, reflecting steady increases since 2003.

Among children aged five to 10, overweight/obesity rates increased from 10.4% in 2019 to 14% in 2021, according to data from DOST – FNRI. Among children and adolescents aged 10 to 19, it increased from 10.7% in 2019 to 13% in 2021.

If no action is taken, more than three in 10 adolescents in the Philippines will be living with overweight or obesity by 2030, said a UNICEF country brief.

WHO data for the Philippines puts obesity for adolescents aged 10 to 19 at 5% as of 2022. Worldwide, it reports the prevalence of overweight (including obesity) among children and adolescents aged five to 19 at 20% in 2022, up from just 8% in 1990. It is also growing in lower-income countries and in urban environments.

A landmark ordinance

Cruz said that he realized “that instead of just providing money, these solicitations should be eye openers that that there are gaps in policy and problems on the ground that need to be addressed.”

He then filed Ordinance No. 803 regulating the marketing of unhealthy, nutrient-poor food and beverages to children under 18 in Taytay, and in January this year, the municipal government passed this ordinance, which targets a major factor that WHO and many health advocates have connected to children’s choices and behavior around food.

When the ordinance took effect in February, Taytay became the first local government in the Philippines to use the law to regulate the harmful marketing of unhealthy, ultra-processed food to young people.

Taytay’s Ordinance No. 803 in a nutshell

What unhealthy food and beverages are prohibited to be marketed to children under 18 in Taytay?

- chocolate and sugar confectionery, energy bars, and sweet toppings and desserts;

- cakes and other sweet bakery products and dry mixes for making such;

- all types of candies;

- heavily salted snacks such as chips;

- instant noodles;

- jellies, ice crushes, slushies;

- soft drinks, alcoholic drinks, flavored mineral water, energy drinks, sports drinks, tea, coffee, powdered juice drinks;

- any processed fruit or vegetable juice with added sugar of more than 20 grams or four teaspoons per serving;

- beverages that contain non-nutritive sweeteners; and

- any food or beverage product containing partially hydrogenated oils or with industrially-produced trans-fatty acid content of more than 2 g per 100 g of total oils and fats.

What is “child-directed marketing”?

It is “marketing that uses: images, sounds or language designed to appeal to children such as characters, personalities or celebrities, children actors or voices, or references to school or play; toys or book giveaways, competitions or promotional giveaways, buy-one-take one, discounts, and pricing bundle strategies; themes designed to attract children (e.g. fantasy or adventure); games or activities that are likely to be popular with children”Where is child-directed marketing prohibited?

– in outdoor environments (including billboards), retail environments, public spaces (including transportation terminals), and public events in the municipality

– “in and within 250 meters from any point of the perimeter of child-centered settings” such as “schools, playgrounds, amusement parks, or other places frequented by families and children” in Taytay

“Powerful food marketing … predominantly promotes foods high in saturated fatty acids, trans-fatty acids, free sugars and/or sodium and uses a wide variety of marketing strategies that are likely to appeal to children,” said WHO.

“Food marketing is pervasive and persuasive,” said a WHO and UNICEF report on protecting kids from food marketing. It “negatively affects children’s food preferences, purchase decisions and consumption behaviors, ultimately contributing to childhood obesity and diet-related disease.”

In Taytay, a huge billboard advertising colorful donuts greets travelers at Tikling Junction, a major intersection. One comes across posters advertising sugar-sweetened drinks and fried snacks near schools — the type of marketing now barred under the local ordinance.

But similar scenes are found in Metro Manila and elsewhere in the country, where advertisements designed to appeal to younger consumers are stuck to the walls and roofs of waiting sheds, or come in the form of life-sized cut-outs of celebrity endorsers in malls.

In a 2023 report, UNICEF said the marketing of unhealthy food to young people “heightens the appeal for children of largely unhealthy food and snacks.”

A lot of soft drinks, too little physical activity, and few vegetables

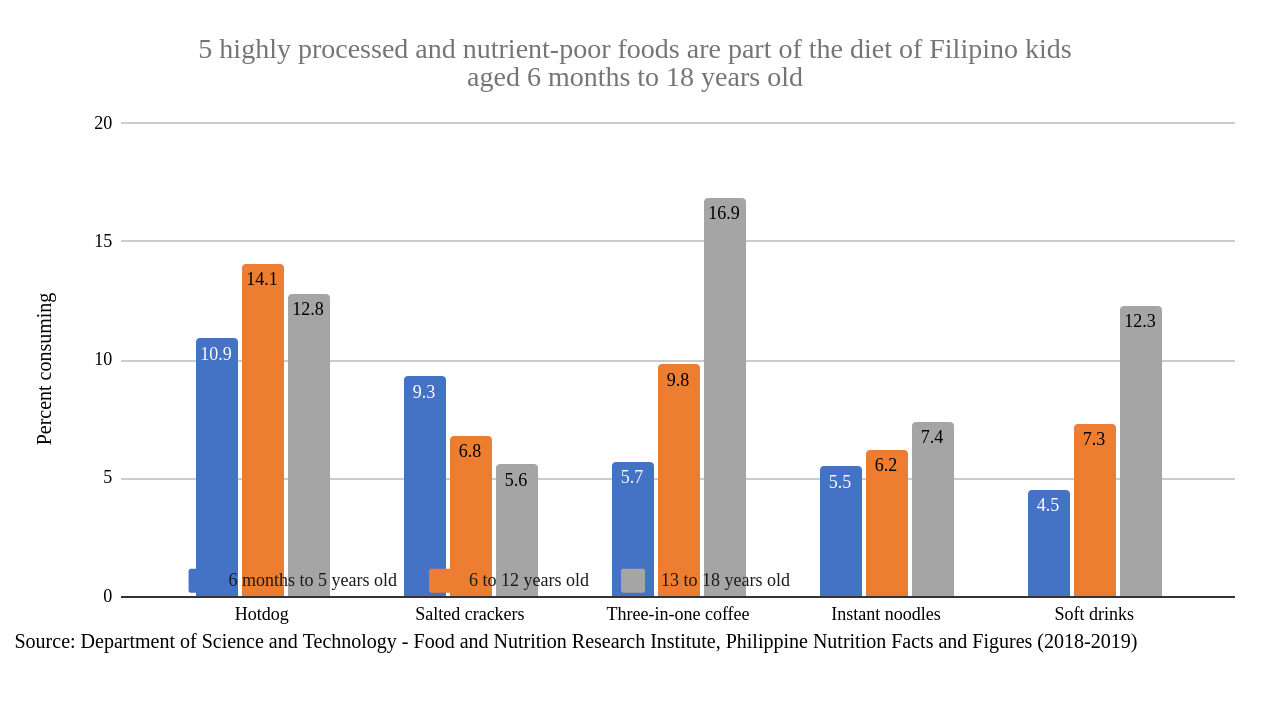

Soft drinks are among the top 30 food items commonly consumed by Filipino kids aged 6 months to 18 years, according to data for 2018-2019 from DOST-FNRI. Other highly processed foods — hotdogs, instant noodles, salted crackers, and three-in-one coffee — are also on the list.

Trends around young Filipinos’ consumption of soft drinks are also evident in the results of WHO-led surveys of adolescents’ health and risk behavior, which have been carried out by national governments across two decades. The same surveys shed light on growing figures of overweight and obese children, as well as levels of physical inactivity among young people — another factor in obesity and a risk factor too for chronic illnesses.

In the 2015 fact sheet for the Philippines’ Global School-based Student Health Survey, 37% of students aged 13 to 17 said they “usually drank carbonated soft drinks one or more times per day during the 30 days before the survey”.

In the fact sheet on the results of the 2019 survey, the question on soft drinks was changed to ask how many respondents “did not drink carbonated soft drinks during the 7 days before the survey”. Only 21.8% percent of students aged 13 to 17 said they did not consume such drinks.

In the 2019 survey, 36.4% of students said they “spent three or more hours per day sitting and watching television, playing computer games, or talking with friends, when not in school or doing homework during a typical or usual day”. This figure increased from 31.9% in the 2015 survey. Only 6.7% of students in the 2019 survey were “physically active at least 60 minutes per day on all 7 days during the 7 days before the survey,” down from 7.6% in the 2015 survey.

A 2019 WHO study — the first global study on physical inactivity among teens in 146 countries — found that the Philippines had an overall “physical inactivity prevalence” of 93.4%. Girls and boys aged 11 to 17 years in the country did not meet current recommendations of at least one hour of physical activity per day. The Philippines ranked second in the world with the most physically inactive adolescents, next to South Korea.

UNICEF Philippines also cites the 2015 Global School-based Student Health Survey results, showing that three-quarters (74%) of children aged 13 to 15 eat less than three portions of vegetables per day.

Children with chronic conditions are more likely to become chronically ill as adults, become disabled, or die prematurely.

“Overweight and obese children are more likely to stay obese into adulthood and to develop non-communicable diseases (NCDs) like diabetes and cardiovascular diseases at a younger age,” a WHO brief said.

It lists the following as the “most significant health consequences of childhood overweight and obesity, which often do not become apparent until adulthood”: cardiovascular diseases like heart disease and stroke, diabetes, musculoskeletal disorders like osteoarthritis, and certain types of cancers.

Legal weapons

In July 2023, WHO released guidelines for countries to use in shaping policies to protect children from the harmful impact of food marketing. It recommends the “mandatory regulation” of marketing of what it calls “foods and non-alcoholic beverages that are high in saturated fatty acids, trans-fatty acids, free sugars and/or salt”.

In September 2023, ASEAN, too, adopted “minimum standards and guidelines” to regulate the harmful marketing of food and alcoholic beverages. Regulating children’s exposure to harmful marketing is “critical to reducing obesity,” said a factsheet by the Global Food Research Program at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in the United States.

There are 12 economies that have national policies regulating food marketing to children in a 2022 list by the Global Food Research Program. These measures range from limits on advertisements and marketing in print, outdoors, broadcast media, and online, including times when they can be aired, such as in Chile.

Taytay’s Ordinance No. 803 is not the first time that laws and regulations have been used in the Philippines to address health behavior issues, including around NCDs and overweight and obesity. In 2018, the country passed legislation imposing a tax on sugar-sweetened beverages.

Meantime, Taytay officials have been preparing the municipality for the implementation of the ordinance. Volunteer nutrition scholars have undergone training for this work, which would include ensuring a ban on advertisements within 250 meters from a child-centered setting, checking if advertisements are targeted toward children and if the promoted food products are classified as unhealthy.

After inspection, they would report to a verifying officer who makes a determination about violations, and can issue a notice requiring the removal of an advertisement within three to five days.

Cruz said barangay officials are conducting an information campaign for six months, visiting every store near schools to inform them about the ordinance. The Taytay government is also helping smaller businesses fix their signages and subsidizing their costs of removing the ads and putting up new and compliant ones.

“By the end of the year, we’ll ask store owners to remove violating posters, and if any remain by the start of 2025, we will penalize them,” he said.

The penalties for violators range from ₱2,000 to ₱2,500 and imprisonment from one to two months. Penalties will be deposited to the Healthy Children of Taytay Trust Fund, to be used for programs to combat overweight and obesity among children.

Apart from Taytay, Valenzuela City in Metro Manila is also debating a proposed ordinance that would prohibit the marketing of processed food items high in sugar, salt, and fat, alcoholic beverages, energy drinks, and soda, to individuals under 18 years of age.

“Our strategy is to approach local government units and build support for policies like this at the local level,” said Sophia Monica San Luis, executive director of ImagineLaw, a public-interest legal advocacy group that provided support for the Taytay ordinance. “Then we can tell national legislators, ‘Look, local communities are interested in this policy, and they find it beneficial.’”

At the national level, proposed legislation was filed in January this year that would require “front-of-package warning labels” for foods high in fat, sodium, or sugar and “regulating” the marketing of such food items to children in the country. The bill, for which ImagineLaw also provided technical advice, was filed by Samar Rep. Reynolds Michael Tan.

“There is no overarching national policy specifically on the prevention of overweight and obesity in children,” according to a UNICEF-WHO toolkit to protect children from the harmful impact of food marketing.

Home-built habits

Taytay’s ordinance and the use of the law to shape healthier choices have drawn mixed reactions. Some say it is but one tool to be combined with better nutrition knowledge and that better nutrition environments and food habits that start at home.

San Luis said, “The biggest inhibiting factor for this policy is that we have a lot of cultural associations with the way food is marketed, with brands.” For example, she said, many Filipinos grew up drinking a chocolate malt drink for its reputed energy-boosting ingredients and still remember a hotdog ad featuring children.

Ma. Lilibeth Dasco, a supervising science research specialist at DOST-FNRI, thinks the ordinance is a step in the right direction. However, she said, “eating healthy food must start in the households, thus selling these food items to parents should be also regulated, and parents must be aware of the harmful effects of consuming highly processed foods not only for their children but for their own health as well.”

Local ordinances help but “two-thirds of their (children’s) meals are often consumed at home,” which is why parents are key to shaping children’s food habits, said John Eric Sulit, a registered nutritionist-dietitian and clinical dietitian at the Philippine General Hospital.

Family practices are important, said Atty. Mary Grace Anne Rosales-Sto. Domingo, regional manager for Asia at the McCabe Centre for Law and Cancer. “But it’s also vital that laws that introduce a more systemic approach to reducing the persuasive power and exposure of children to unhealthy food marketing are in place.”

This story was produced under the “Communicating NCDs” Media Fellowship by Probe Media Foundation Inc. (PMFI), Reporting ASEAN (RA) and World Health Organization (WHO). The views and opinions expressed in this piece are not necessarily those of PMFI, RA, and WHO.