Repatriation comes with welcome banners, but what next? Photo: Screenshot from Philippines’ Department of Foreign Affairs website

Emerson’s last memory of the world before COVID-19 was a night in Honolulu in Hawaii, sometime early March 2020. The cruise ship where he works as an entertainment technician docked there overnight, allowing him and his fellow employees some time off.

“We went to Jollibee,” 35-year-old Emerson said, referring to the Philippine fastfood chain that has gone global, much like the more than 10 million Filipinos, a tenth of their country’s population, who work in just about every country in the world, on land or at sea. “Filipino food” is how Emerson calls Jollibee’s meals, which range from hamburgers to fried chicken, because they have become comfort food to Filipinos overseas.

Emerson recalls just wandering around the city, enjoying a brief break from being at sea and from his tasks, which include ensuring that the entertainment shows for passengers run smoothly.

On 11 March, soon after Emerson’s night out in Honolulu, the World Health Organization declared COVID-19 a pandemic. The world effectively shut down, and remains so, for seafarers, including cruise-ship workers. For Emerson, it meant a month and a half adrift on land, a huge chunk of that time spent in isolation.

“Cruise line operations in the entire world halted, we lost work,” Emerson recounted. “We have no idea when the cruise industry rebounds.”

More than three months since, scores of countries, including in Southeast Asia, have eased, or have started to ease, limits on mobility and economic activity. Some are discussing how to restart some international travel through ‘travel bubbles’ among selected countries.

No idea when- or if

But there is little sign that the cruise ship industry, whose confined environments made its vessels a risky setting with COVID-19, is about to set sail again soon. The earliest realistic date seems to be 2021.

What is clear is that the impact of this shutdown is being felt sharply, severely and perhaps for the long term, or even permanently, in the Philippines, a country of some 108 million people that provides about a third of all staff in the world’s cruise ships.

The toll goes far beyond the loss of jobs. “The two biggest feelings the seafarers have -number one (is) the feeling of failure, not because it is their fault, not because they are not qualified or not willing to work, but the situation is what it is,” Paulo Prigol, a Brazilian priest who is Manila-based Asia coordinator for Stella Maris, a Catholic charity that supports seafarers worldwide, said in a May webinar by the Philippine Migration Research Council.

Prigol added: “The second biggest fear is ‘I am unable to provide for my family’, and that can extremely torture the seafarer. Some of them, I can see in their faces, they want to give up. But if they give up, what is the option?”

From his center’s survey of 1,272 seafarers, Prigol said 64 percent said they wish to apply for onboard ship duty again – and only 36 percent said they wanted to return to their hometowns.

“This displacement has been very painful physically, psychologically and even financially to our seafarers,” explained Lucia Tangi, a University of the Philippines journalism professor who has been doing research on women Filipino seafarers. Many have incurred debts in order to take up seafaring, she added.

The Philippines’ pattern of exporting human labor has been underway for nearly 50 years. Filipinos work as nurses and caregivers, engineers, domestic workers and teachers, among others, in all continents.

Since February, many of them have been flying home day after day – jobless. Seafarers make up six in 10 of the more than 51,000 migrant workers that have been repatriated as of 21 June.

Then, there are more than 8,000 others that have been stuck on board at least 26 cruise ships in Manila Bay, the Philippine government said in early June. These include the 19-deck Ruby Princess, the center of the biggest COVID-19 cluster in Australia. It is one of many that have come to bring home their huge numbers of Filipino staff, up to 700 or more at a time.

Some 325,000 Filipinos work aboard cruise ships in jobs ranging from management, entertainment, food and beverage, and housekeeping. By Tangi’s calculations, up to 100,000 Filipino cruise-ship staff may lose their jobs due to the pandemic.

If other migrant workers might be able to wait out the pandemic, seafarers wonder not just about whether they will have future contracts – but whether there is a cruise ship business, globally, to talk about.

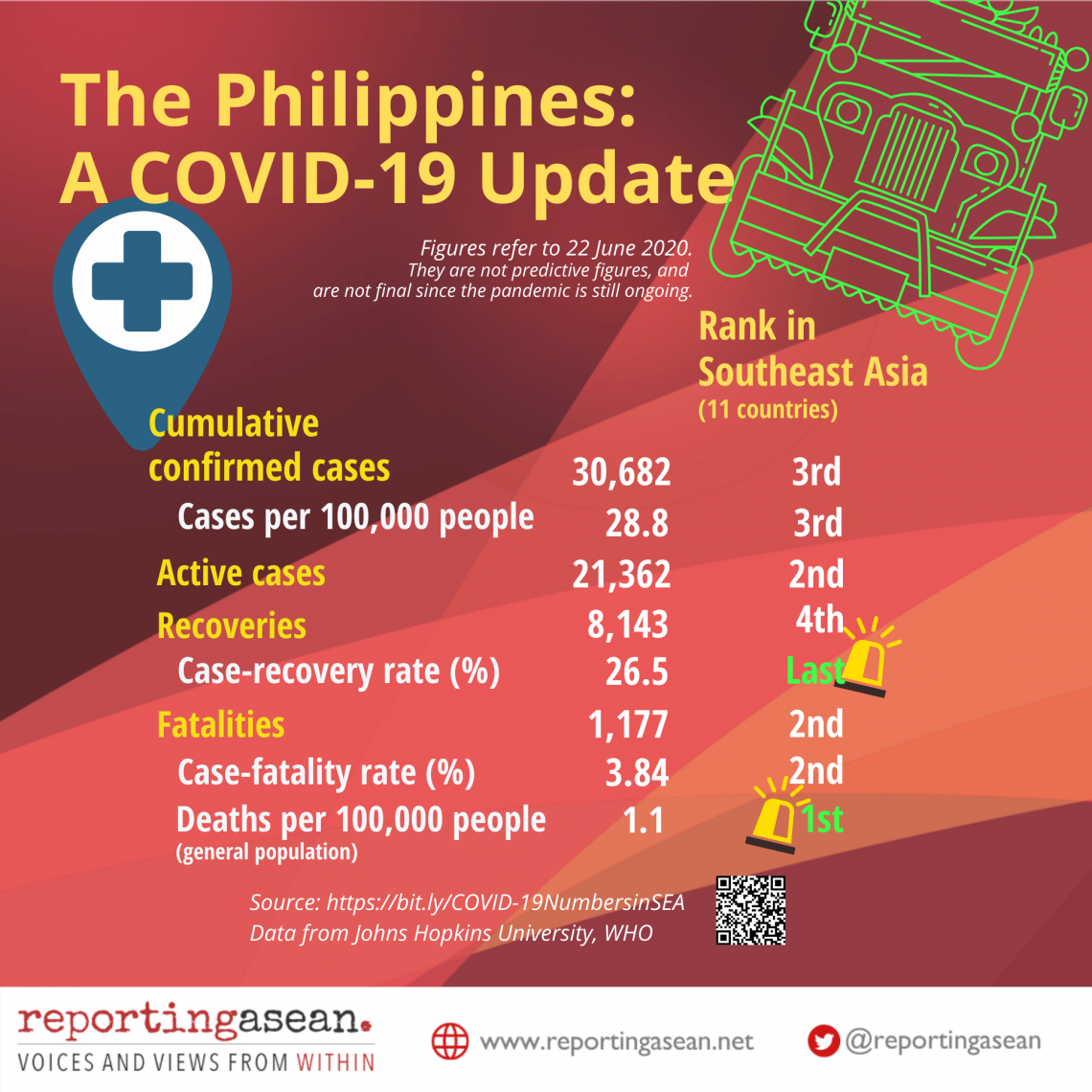

Meantime, what are they coming home to? The Philippines has imposed one of the longest, most stringent lockdowns in the capital Manila and the main island Luzon since 17 March, but its cumulative and active cases continue to rise. Its case-recovery figure is lowest in Southeast Asia, and fatality figures remain among the highest. (See infographic.)

Infographic on the Philippine COVID-19 profile (as of 25 June, updated)

The government eased its restrictions a bit and allowed more economic activity since 1 June, but these are very early days in its rehabilitation plans. The Philippine government’s key policy response to the pandemic is a 595.6 billion-peso fiscal package (USD 12 million), equivalent to 0.3 percent of its GDP, for vulnerable individuals.

But the figures are grim: Remittances inflows from overseas workers are expected to drop by up to 13 perccent this year (from 33.5 billion dollars in 2019) and dent the country’s GDP growth by 0.4 perccent. A record high 7.3 million unemployed Filipinos was reported by the Philippine Statistics Authority in April 2020. In May, the government adjusted its projected economic contraction to 2 percent to 3.4 percent for the year.

Lack of social protection

Much of the response to the displaced workers’ return has been in repatriation and cash assistance to documented workers of 10,000 pesos (about 200 dollars). The government has been publicizing opportunities for training.

But the Philippine government was caught ill-prepared, without enough means of social protection in place.

“One set of responses must involve intelligent logistics to facilitate return of the seafarers — random testing, quarantine, isolation as needed, transportation home, resettlement with family,” said Thetis Mangahas, a former deputy chief for Asia-Pacific of the International Labour Organization (ILO). “Counseling and other resources to be made available at all stages of the process.”

For many, returning home threw up challenges ranging from stressful travel, strict quarantine controls and testing, overly long isolation and waiting periods, not to mention the stigma of having worked aboard cruise ships. Migrant advocacy groups put the number of returnees in quarantine at more than 22,000 at end-May.

In June, viral photos of overseas workers sleeping outside the Manila airport drew anger among many.

To accusations by activists that the migrant workers were being “dumped like garbage” upon return, Philippine presidential spokesman Harry Roque maintains that the government has covered repatriation costs and the costs of COVID-19 testing. “That’s not garbage treatment. That is VIP treatment,” he was quoted as saying.

Returning workers undergo a two-week quarantine in hotels, and are tested for COVID-19, after which they, if clear, are allowed to proceed to their provinces. At times, they have had to undergo another round of quarantine. It is not uncommon to hear of returnees spending 40 days in combined quarantine and waiting periods.

Emerson was tested for the virus on May 9. “They said results would be out in three to five days.” That stretched to 10 days, during which he stayed aboard his ship on Manila Bay.

Emerson spent those days watching the ship’s available television channel. After testing negative, he had to wait three more days for clearance to be allowed home, which is a neighborhood located within the capital itself.

For her part, 32-year-old Cez, who worked as a cruise ship chef, found herself in quarantine aboard her ship when it docked in a port of Britain. Being allowed to use the ship’s recreation facilities made the quarantine bearable, she recalls. “I feel for the crew stranded in Manila Bay,” said Cez, now back in her hometown.

“I expect lingering resentment among OFWs (overseas Filipino workers) on the almost hostile policy and program response to their premature return,” said Mangahas. “While some type of quarantine might have been expected by the OFWs especially the seafarers, the lack of coherent national and local level response to their return will negatively affect the way that our foreign-based workers look to their country and their long-term plans for investment and return.”

DFA personnel welcome seafarers from Norwegian cruise ships. DFA photo.

Anyone aboard?

There is another element in the uncertainties around the cruise ship industry which had been expecting 32 million passengers in 2020, according to the Cruise Lines International Association.

These days, ‘cruise ship’ calls to mind a link to COVID-19. The Ruby Princess caused a stir in Australia when asymptomatic passengers were allowed to disembark in Sydney in mid-March. Earlier, the Diamond Princess, was quarantined off the coast of Yokohama, Japan with around 700 positive cases aboard for nearly a month.

These high-profile examples led to them being shunned, prevented from docking or its passengers from disembarking. Some destinations, like the Seychelles, have announced a ban on cruise ships through 2021.

“It’s probably going to be next year,” Emerson said of the return of cruises, but admits that this hinges on a lot of factors going right. “It depends if people would still want to book cruises.”

“Honestly, our passengers are mostly senior citizens,” Emerson said. Beyond the fact that people above 60 are at greater risk of getting COVID-19, the biggest markets for cruises are North America and western Europe, also the hardest-hit by the pandemic.

From heroes to villains

Before COVID-19, seafarers were sought out by family, friends and community members, bearing presents and money, when they came home. But amid the pandemic, returnees have become suspect to their own communities, who see them as outsiders who potentially bear an unseen, dangerous pathogen. “I am afraid we are developing something that we call stigma. The hero becomes the villain and that is going to become very heavy for the family,” Fr Prigol added.

Mangahas suggests that the government go beyond repatriation to provide support for those who want to go back to overseas work, such as by targeting markets that have coped better with COVID-19.

“Assuming that we wish to [improve] our seafarers’ presence globally, we need to invest in setting up new cooperative processes to meet the demand for manning in these times — health testing again, digital registries, fast-tracking of employment/boarding of seafarers as well as strengthening social protection,” Mangahas said.

Some of what lies ahead in the future is already evident. Prigol says applicants for jobs aboard cargo vessels are being asked two questions: ‘How safe is your quarantine area?’ and ‘Do you have swab test results?’ These give clues as to what the country needs to prepare for, he says, “so that when they open it again, our Filipino seafarers will be the seafarers of choice”.

The country’s economic planning agency said it aims to facilitate the employment of repatriated overseas workers “through proactive job matching and competency assessment and certification, along with online skills upgrading and retooling programs, especially for telecommuting and e-commerce-friendly jobs.”

For those who decide to stay in the country for good, the government needs to provide ways of helping them find relevant alternative livelihoods, Mangahas adds. “If we want our workers to stay home, how about improved employment services, a registry of those returning, some private sector partnership on re-employment home, a free certification on their skills acquired abroad, upgraded retraining especially for seafarers,” she said in an online post.

Many other seafarers are still stuck at sea. Prigol estimates that there are “at least” 40,000 Filipinos among the 150,000 to 200,200 seafarers that the ILO has said remain on vessels that are unable to dock and do crew changes as of early June. Cruise ship workers could only be “the first wave” of displaced sea-based workers, said Prigol. “The second wave is the commercial ship (workers).”

Wait and see

For Emerson and Cez, it remains wait and see. “Since we’re still on lockdown, one can’t really plan much,” Cez said.

Even if a few cruise ships do restart in 2020 and others in 2021, Tangi said: “There will be lesser passengers, and less passengers means there will be less Filipino seafarers on board cruise ships.”

“I told my wife we could probably do online business. I’ve been reading a lot about people selling things online,” Emerson said. “I’m just extremely happy I’m with my wife and family now.”

*This feature is part of the ‘COVID-19 and Southeast Asia’ series published by the Heinrich Boell Foundation Southeast Asia, in collaboration with the Reporting ASEAN programme.