Text and photos by LUCIA P. TANGI

Text and photos by LUCIA P. TANGI

(First of two parts)

The image of an olive-skinned man or a “barako” who has “a girl in every port” usually comes to mind when one mentions the word seafarer. The stereotype stems from the dominance of men in the maritime industry since the country started its massive labor export in the1970s.

This “masculine” and “macho” image of Filipino “seamen” may soon gradually fade as more women choose to work on board international vessels, mostly on passenger cruise.

But empowering these women at sea is altogether another story. Most of them occupy lower-paying jobs—as chambermaids, waitresses or other guest relations—unlike their male counterparts, a consequence of gender stereotyping.

The rise of Pinay seafarers

Only 225 out of the 230,000 Filipino seafarers registered from 1983 to1990 were women, a study by the International Maritime Organization (IMO) in 2000 showed.

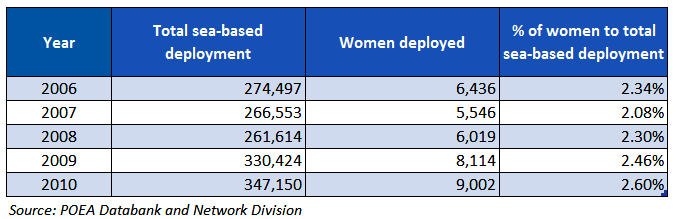

By 2006, the number of Filipino women seafarers deployed had risen astronomically to 6,436, according to statistics from the Philippine Overseas and Employment Administration (POEA) Databank and Network Division. That’s almost 29 times the number recorded by the IMO.

Their ranks continue to swell—to 8,114 in 2009 and 9,002 in 2010.

Today, women seafarers account for 2 percent of the total number of sea-based workers deployed from 2006 to 2010. The proportion, albeit small, is significant: It was less than 1 percent in the 1980s and 1990s.

Women shied away from shipboard employment decades ago because of fixations that seafaring is “an exclusive male preserve” and the prevailing cultural ideology that women should stay at home, the IMO study said.

Women shied away from shipboard employment decades ago because of fixations that seafaring is “an exclusive male preserve” and the prevailing cultural ideology that women should stay at home, the IMO study said.

“There may also be cultural resistance to women working outside the home,” IMO’s Pamela Tansey said in her 2000 study.

“But the principal objections to employing women at sea appear to center around the lack of adequate separate facilities for women on board and stringent physical requirements,” she said.

Women who work as chamber maids, waitresses and massage therapists have to pass the same Basic Safety Training like any other seafarer, before they can get their Seaman’s Identification Record Book (SIRB) or commonly known as “Seaman’s book.” The most difficult part of the safety training are diving on a pool from 20 feet high and surviving a simulated fire situation.

Global demand for women seafarers

Filipino women began setting aside these reservations in the past decade owing in part to the growing popularity of passenger cruise and the lack of economic opportunities in the country. Many of them have been enticed by the promises of cruise ship jobs as a “chance to see the world.”

Federico S. Concepcion, general manager for Cruise and Manning Services of NYK-Fil Ship Management, recalled in an interview years ago how the demand for cruise tourism surged in the 1990s after the box office hit “Titanic” was released. This, in turn, led to the rise in the demand for Filipino women seafarers to work on cruise ships, he said.

Jeremy Cajiuat, project development officer of the International Seafarers’ Action Center (ISAC) Philippines Foundation, said, “With the further rise of the cruise business and the influx of more and more ships into the business, there will likewise be a rise in employment onboard these ships for women.”

The 2015 Cruise Industry Outlook released by the Cruise Lines International Association in February shows the number of cruise ship passengers rising 24 percent from 17.8 million in 2009 to 22.1 million in 2014. Cruise operators expect the number of passengers this year to reach 23 million, up 4 percent from last year’s figures.

The CLIA also reported that its members are investing $25.65 billion to build 55 new ships between 2015 and 2020. The commissioning of new ships means more jobs will be generated for seafarers within the next five years.

A cruise ship has a crew of from 800 to 1,500. There are 400,000 jobs available on cruise ships, and total wages reached $6 billion last year, according to the Cruise Ship Jobs Network.

Gender mainstreaming

Retired Vice Admiral Eduardo Ma. R. Santos, presidentof the Bataan-based Maritime Academy of theAsia and the Pacific (MAAP), also traced the rising number of Filipino female seafarers to calls for greater women’s participation in various sectors, including the maritime sector.

“The movement for greater participation of women in society has really inspired more women to become seafarers,” he said.

The integrationof women into the male-dominated seafaring industry is often attributed to the calls for gender mainstreaming by the United Nations in the1980s after the Conventionon the Eliminationof All Formsof Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW) was ratified.

In support of the UN agenda on women, the IMO launched the Women in Development (WID) program in 1988 to boost the number of women in the maritime sector and improve women’s access to maritime training and technology.

‘Women’s jobs’

But the commercial value of women and gender stereotypes have also been driving the growth of female seafarers.

“Filipino women waitresses are perceived to be more caring, especially with the children and senior passengers (on cruise ships),”Concepcion said.

Cajiuat is more blunt. He said, “(Filipino) women seafarers are being hired due to their ‘docile’ nature: They are still considered the weak gender and are exploited more in terms of hours of work, excessive workload, less food consumption, and the extra attraction of beauty and charm to entice more guests.”

So even as the number of Filipino women entering the maritime sector has leapt in recent years, women seafarers have not been empowered.

The jobs on a passenger liner can be divided into three categories: the deck, the engine and the hotel and services departments.

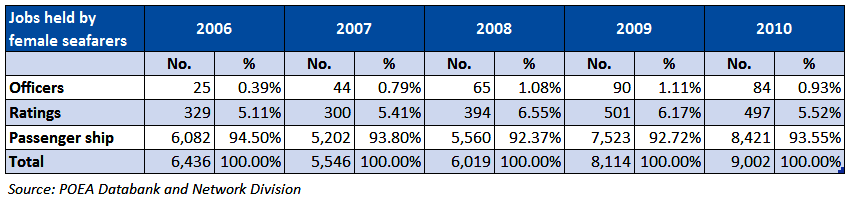

Based on statistics supplied by the POEA Databank and Network Division, officers only accounted between 0.4 and 1.8 percent of the total number of Filipino women seafarers, while ratings or non-officers accounted between 5 and 6.5 percent of the total number of women seafarers from 2006 to 2010.

Based on statistics supplied by the POEA Databank and Network Division, officers only accounted between 0.4 and 1.8 percent of the total number of Filipino women seafarers, while ratings or non-officers accounted between 5 and 6.5 percent of the total number of women seafarers from 2006 to 2010.

The bulk of Filipino women seafarers work in the hotel and services department of passenger ships. Nine in 10 of them are chambermaids, waitresses, women kitchen crew, entertainers, cleaning crew, casino dealers, massage therapists, cashiers, guest relations officers, female security personnel, nurses and other medical personnel, and other office personnel.

They hold what are called “women’s jobs,” or jobs considered extension of their reproductive duties, which are usually among the lowest paid in the ship’s hierarchy.

Cabin girls and massage therapists interviewed for this research say they receive a basic pay of $50 per month. They augment their remittances through tips from customers and sales commission for products that they offer to passengers.

Assigning women’s jobs to female seafarers is stereotyping, Cajiuat said.

Ironically, being assigned “feminine”jobs doesn’t mean the women seafarers are spared “masculine” tasks.

The Filipino female seafarers “also have lifting-and-carrying tasks and are trained for strenuous jobs such as firefighting and crowd control,” Cajiuat said.

(To be concluded)

(This two-part report is based on the author’s M.A. thesis, “Pinays Aboard: A Study on the General Working Conditions on Filipino Women Seafarers On Board International Vessel,” submitted to theCollege of SocialWork and Community Development, UP Diliman.)