“Of course, Imelda and I denied it.”

That was what then president Ferdinand Marcos wrote in his diary for September 21, 1972. It was his response when asked by Jose Aspiras and Carmelo Barbero, two of the strongman’s most loyal political lieutenants from the “northern bloc,” if rumors were true that he would declare martial law within 48 hours.

While he denied it publicly, Marcos had secretly signed Proclamation 1081 imposing martial law in the entire country. The public would know about this only on the evening of September 23 when he announced it on live television, saying that martial law was the appropriate response to meet the growing threat from the armed Left and Muslim rebels.

Many had suspected this would happen, but only a dozen men knew for sure and not even all of them were aware of the timing. Within this clique, there were differences in what the “Seven Wise Men” or the “Group of Seven” knew beforehand to what the rest of the “Rolex 12” would eventually come to learn and implement. Close Marcos aides, including those tasked to prepare plans for or study the feasibility of martial law in the country, were surprised when it finally happened.

But one man already held a copy of Proclamation 1081: then US ambassador to the Philippines Henry Byroade.

Oplan Sagittarius by VERA Files on Scribd

Various authors and sources have reasonably surmised that Marcos started to seriously plan for martial law when he won his second term in November 1969. While his stated rationale for imposing martial law changed and shifted in 34 months, what remained unchanged was his resolve to gain dictatorial powers. Marcos devised ways to keep secret his ambition to gain political dominance even as he started enlisting the help of a chosen few to justify martial law and how best to execute his plan given the expected opposition.

If the memoir of martial law administrator Juan Ponce Enrile would be believed, Marcos, then newly re-elected, began planning for martial law in early December 1969. Marcos had asked Enrile to “study his powers under the commander-in-chief provisions of the [1935] Constitution” as he “was foreseeing an escalation of violence and disorder in the country.” His commander-in-chief told Enrile he could ask for help in completing the study, but the project should be done “discreetly and confidentially.” Enrile enlisted two 1954 magna cum laude graduates from the University of the Philippines (UP) College of Law, Efren Plana and Minerva Gonzaga-Reyes.

As he was hatching plans for imposing martial law, Marcos was quoted as saying in a November 14, 1969 Manila Times article that he would never become a dictator because this would “invite a violent reaction from the people.”

Enrile made it appear in his memoir that he was Marcos’s sole brain trust, but this was not the case. Marcos liked to compartmentalize when farming out sensitive and crucial work for his martial law plans.

Gen. Rafael Ileto told author Conrado de Quiros in Dead Aim: How Marcos Ambushed Philippine Democracy that Marcos had asked him to look into the military strategy needed for martial law . Jose Almonte and his boss, then executive secretary Alejandro Melchor Jr. were assigned to study authoritarian regimes in Asia and Adrian Cristobal was tasked to envision a government without a Congress. Ronaldo Zamora had to study the early years of American occupation when the governors-general ruled by decree. Even as he was about to declare martial law, Marcos was still asking Blas Ople to look into the workings of totalitarianism in the Soviet Union.

At some point, Marcos even had Philippine embassies in authoritarian countries draw up reports on how their host governments worked.

But only Marcos knew how this surfeit of information fit together in his pursuit of a dictatorship. When some of these studies proved unsupportive of what he had in mind, Marcos treated the authors with suspicion — as in the case of Ileto, Almonte, and Melchor.

In late January 1970, Enrile submitted to Marcos a compendium of the results of the study. A week later, Marcos instructed him “to prepare the documents to install martial law in the country.” Enrile claimed that, working alone (save for Simplicio Taguiam, Marcos’s private and confidential secretary who did the typing), it took him six months to complete what would eventually become Proclamation 1081.

As the First Quarter Storm raged in 1970, Marcos intimated to the United States that he may resort to martial law. The attack on Malacañang mostly by student activists during the January 30 Battle of Mendiola almost prompted Marcos to declare martial law or at least, suspend the writ of habeas corpus right then and there. Ileto has claimed to have dissuaded Marcos from taking this course of action.

In a memorandum dated February 7, 1970 to US President Richard Nixon, Henry Kissinger, then assistant for national security affairs, quoted a report by Byroade describing “a rambling conversation with a very distraught and unnerved President Marcos.” Kissinger said Marcos wanted the ambassador’s ‘active help’ as he might have to impose martial law. Marcos wanted to know if Byroade would ‘stand behind him.’”

“Byroade reacted cautiously to keep us from being drawn into this situation. He tried discreetly to suggest the need for social programs and land reform, and to head off drastic actions such as martial law,” Kissenger wrote.

In a marginal note, Nixon wrote that he “doubts this line’s effectiveness.”

With US military bases still in the country then and the US war of aggression in Vietnam a hotspot in the Cold War, Washington was keen on constantly knowing what Marcos was up to as his actions would have bearing on its strategic interests. There were also substantial American economic interests in the country that must be protected.

Almost a year later, as related in a January 15, 1971 memorandum of conversation involving Nixon, Byroade, and John H. Holdridge, a member of Nixon’s National Security Council, Marcos asked the White House if the US would oppose or support his martial law plan.

“The President [Nixon] declared that he would “absolutely” back Marcos up, and “to the hilt” so long as what he was doing was to preserve the system against those who would destroy it in the name of liberty. The President [Nixon] indicated that he had telephoned Trudeau of Canada to express this same position. We would not support anyone who was trying to set himself up as a military dictator, but we would do everything we could to back a man who was trying to make the system work and to preserve order. Of course, we understood that Marcos would not be entirely motivated by national interests, but this was something which we had come to expect from Asian leaders. The important thing was to keep the Philippines from going down the tube, since we had a major interest in the success or failure of the Philippine system. Whatever happens, the Philippines was our baby,” the memo stated.

In late May 1972, Byroade had another conversation with Marcos that he reported to the US State Department. He wrote that again, Marcos “talked of the ‘great upsurge of communist insurgency threat in the country,” noting that the Philippine leader had warned that he “might have to reinstate martial law. He asked again if we would support him or at least not oppose him.” To this, Byroade said that he ‘mumbled that our position on that had not changed, but added the hope that he would not find such a move necessary as I thought it would clearly at this time tear the nation apart into opposing factions.’”

Byroade may have made a mistake by using the word “reinstate” in his report — unless, of course, he and Marcos were referring to the suspension of the writ of habeas corpus that was implemented in response to the August 21, 1971 Plaza Miranda bombing.

September 1972 was ushered in by a spate of bombings in Metro Manila, now more frequent than in previous months. For the US Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), “at least some of the bombs were set by pro-Soviet terrorist groups, that none can be definitely traced to the Maoists.”

1972 09 08 Letter of Enrile to Marcos Re Urdaneta Village Meeting by VERA Files on Scribd

In hindsight, the CIA half failed in its intelligence effort here. Ever since Jose Ma. Sison founded the Communist Party of the Philippines (CPP) in December 1968 espousing Marxism–Leninism–Maoism as a breakaway faction from the old Partiko Komunista ng Pilipinas, a rivalry — sometimes lethal — had existed between the two groups. In his book, de Quiros wrote that a leader of the CPP’s Armed City Partisans admitted that the group “did carry out some bombing . . .but not during that period [August-September 1972] . . . we did not bomb without reason . . . and we made sure no innocent bystanders got hurt.”

But as later admissions and pieces evidence would prove, the bombings were, in fact, the work mostly of Marcos’s own military. Ironically, whatever the motives of the armed partisans from the Left, their violent actions combined with those of the military worked to sow fear and chaos among Filipinos. It was a near-perfect condition for Marcos to declare martial law.

As recorded in Marcos’s diary entries, it appears that after each passing week in September, critical elements in the declaration of martial law were agreed on and put in effect by the “Rolex 12.” The potent surprise of springing martial law on an anxious and terrified populace continued to be a well-guarded secret even after Benigno “Ninoy” Aquino Jr., Marcos’s foremost political adversary, had almost exposed a crucial part of it.

In his September 7, 1972 diary entry, Marcos reveals he had finalized his martial law plans after one development: Enrile, then defense minister, informing him that Aquino had invited him to discuss “a matter of the highest urgency and of national importance,” and they were set to meet that evening.

In Enrile’s memoir, he narrated that the meeting happened almost around midnight at the residence of their common friend, Ramon Siy Lay, at Urdaneta Village in Makati where Enrile also lived. During the meeting that lasted for over an hour, Aquino disclosed information that he insisted Enrile keep confidential. Enrile wrote that he protested, but was “already tired and sleepy” and wanted to end their conversation. So he agreed.

But when he got home, Enrile immediately called Marcos and briefed him on what Aquino had revealed. Typing it himself, Enrile also wrote a report that he sent to his boss in the morning. Enrile wrote that he betrayed Aquino because he felt that Marcos needed to know for “the very obvious national security implication of the matter brought to [his] attention.”

Marcos and Enrile used what transpired in the Urdaneta meeting to counter what Aquino was about to publicly reveal.

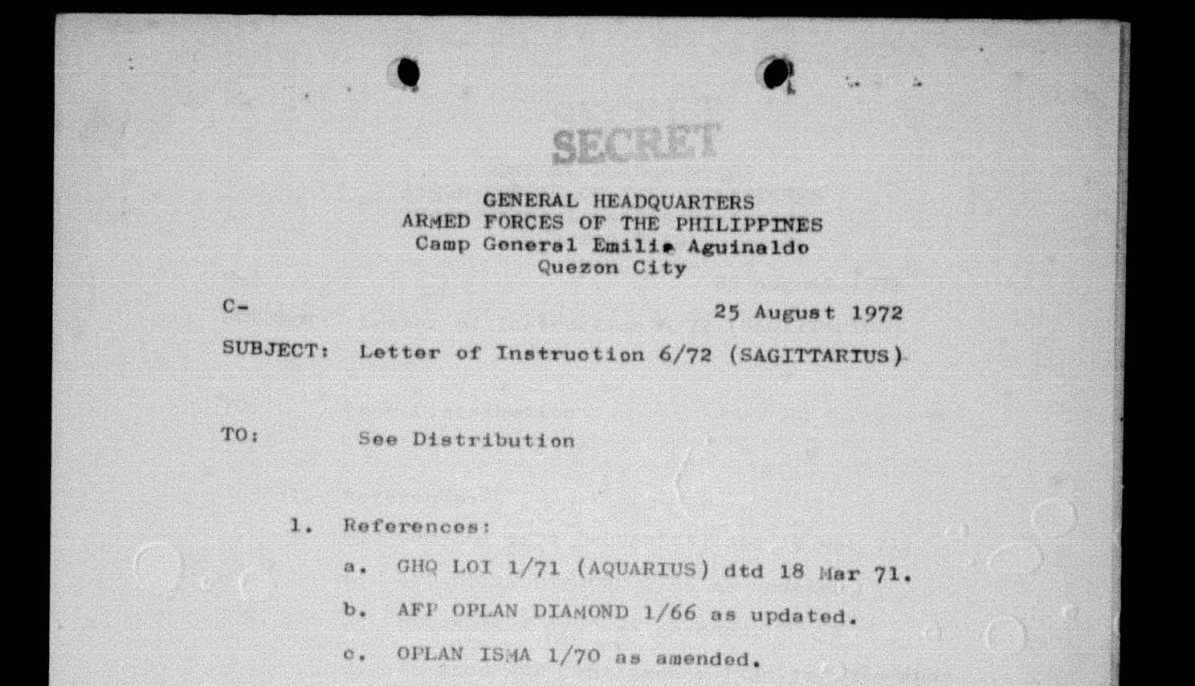

On September 13, 1972, Ninoy, speaking in the Senate, exposed Oplan Sagittarius, the plan for the imposition of martial law leaked to him by sources from the Armed Forces. In his book, In Our Image: America’s Empire in the Philippines, Stanley Karnow wrote that Aquino had in fact brought the information to the US Embassy the day before but Byroade did not believe him.

Both Marcos and AFP Chief of Staff Romeo Espino denied that Oplan Sagittarius was a plan to place the Greater Manila Area under the control of the constabulary before imposing martial law in the entire nation. They said that it was merely a contingency plan to coordinate military and police response to violent acts by the communists.

In fact, Marcos would insist via his ghostwritten books such as Notes on the New Society that he had tricked the opposition with a fake version of Oplan Sagittarius. He said that Ninoy’s claim that the plan was for the imposition of martial law, including the takeover of certain industries, was indeed based on documents obtained from his intelligence network, but these papers were just part of the “dummy plans made to spot security leaks in [their] organization.”

Based on a copy of a document with the subject title “Letter of Instruction 6/72 (Sagittarius)” dated August 25, 1972, which was among those found in Malacañang after the February 1986 revolt, Sagittarius involved equipping all AFP units with “as many rifle (Inf) platoons, companies and battalions as possible with the capability of sustained employment for at least 48 hours without resupply in both conventional and unconventional warfare.” General Headquarters would announce daily one of four internal defense conditions (IDCs) in “each military zone; in each operational area of task forces under GHQ, and in the Greater Manila Area.” Each IDC level, from normal to IDC III, would entail increasing centralization of operational command and under IDC III, “GHQ assumes overall responsibility for the conduct of operations to restore normalcy or reduce internal threats,” while all camps, posts, and stations would maintain 100 percent “effective strength.”

According to a document attached to the LOI, the conditions warranting IDC III include “intensified and widespread insurgency” including, among others, “widespread offensive operations against government troops,” paralyzing “massive civil disturbance,” “imminent threat or confirmed indications of insurrection/rebellion/secession” and “large scale breakdown of peace and order or threat of civil war as a result of political upheaval.”

In short, if LOI 6/72 is the actual Oplan Sagittarius referred to by Marcos and Espino, it did not involve martial law. Before the nation discovered that martial law had been enforced, the national situation would not even merit an IDC III declaration, based on news accounts and various assessments of the offensive capabilities of the CPP-NPA which had no capability to seize power or incite a high-intensity civil war.

All these fine points, however, were lost in the media blitz that Aquino launched against the Philippine leader, who fought back. Writing in his diary on September 14, Marcos planned to “start another raging controversy,” using what he knew from the Urdaneta meeting.

On September 16, the Malacañang press office released a statement from Marcos timed for the Sunday edition of the major broadsheets. In the press release, Marcos accused Liberal Party (LP) leaders of meeting with Jose Maria Sison, CPP founder and chairman, where they talked about “a common plan…in the event of a revolutionary situation.”

This was not entirely correct, based on a September 8, 1972 letter from Enrile to Marcos marked top secret which was also recovered from Malacañang. In the letter, Enrile said that Aquino had told him that CPP leaders he met with in Dasmariñas Village earlier that night had broached the possibility of an alliance with the Liberals if Marcos declared martial law, which they viewed as a precondition for an actual CPP-LP coordination. According to Enrile, Aquino told Sison “something about his duties as a duly-elected senator of the Republic and so forth” when asked about the LP’s “post-martial law-plan.”

But Sison did not meet with Ninoy. In his book, de Quiros wrote that years later, Julius Fortuna of Kabataang Makabayan and a close Sison associate, admitted that it was he and a few that others who met with Aquino in Dasmariñas Village. It is unclear if it was Aquino or Enrile who dragged Sison into the story.

Marcos likewise said in his statement that the meeting vaguely involved a discussion on the landing of weapons by the M.V. Karagatan at Digoyo Point in Isabela, the bombings in Manila, and an increase in the strength of the CPP’s New People’s Army. Marcos did not mention that, as narrated by Enrile, Aquino said that the CPP had denied involvement in the bombings and was “non-commital” about the M.V. Karagatan incident, which was definitely an attempt to ship arms from China to the NPA.

Marcos’s pronouncements forced Aquino and the LP leadership to issue denials. To a certain degree, the Malacanang statement dampened the impact of Aquino’s Oplan Sagittarius exposé and these media distractions proved to be the perfect camouflage for what was really going on.

On September 13, as his only son, Bongbong, celebrated his 14th birthday in Malacañang and media attention was focused on Aquino, Marcos wrote in his diary: “We agreed to set the 21st of this month as the deadline” for declaring martial law. By “we” Marcos meant Enrile and some advisers that he did not name.

The following morning, Marcos met with Enrile, Espino, Army chief Maj. Gen. Rafael Zagala, Maj. Gen. Fidel Ramos, Police Constabulary chief Maj. Gen. Fidel Ramos, Air Force head Maj. Gen. Jose Rancudo, Adm. Hilario Ruiz who headed the Navy, Maj. Gen. Fabian Ver, chief security, Intelligence chief Col. Ignacio Paz, commander of the First PC Zone Gen. Tomas Diaz, Metrocom Chief Col. Alfredo Montoya, Rizal PC commander Col. Romeo Gatan, and Eduardo “Danding” Cojuanco. The so-called “Rolex 12,” supposedly because Marcos gifted each of them the expensive watch. (Espino, however, later told De Quiros that what Marcos actually gave them were fake Omega watches that broke easily.)

Alex Brillantes Jr., in Dictatorship and Martial Law: Philippine Authoritarianism in 1972, identified the “Seven Wise Men” within the Rolex 12 as Marcos, Enrile, Ver, Diaz, Montoya, Gatan, and Cojuangco. These were the men more deeply involved in the planning of martial law. Diaz, Montoya, and Gatan were relatively junior officers at the time were and as de Quiros said, “Not knowing that their superiors were included in the plan, they were not anxious to open their mouths, lest they pay dearly for it. Their superiors in turn were not anxious to ask questions, lest they be thought of as being disloyal. And neither group was anxious to leak the plan to the outside world, lest they be traced as the source.”

By September 14, they were all ready to turn their plans into specific missions. Marcos remained mum on when exactly he would start exercising his dictatorial powers but with daily meetings starting that day, they all knew it would be soon.

On the evening of that day, as if to signal the ominous turn that Marcos had made, a major spill of formaldehyde happened in Manila’s port area. “Manila had entered the last days of Philippine democracy,” William Rempel noted in Delusions of a Dictator, “smelling vaguely like a morgue.”

Strange omen that it was, Marcos had yet to murder Philippine democracy so the secrecy remained.

A mass rally organized by the Movement of Concerned Citizens for Civil Liberties (MCCCL) was held at Plaza Miranda in Quiapo. (Photo courtesy of Philippines Free Press Magazine) Photo downloaded from Official Gazette.

In a September 15, 1972 telegram to the US State Department, Byroade related that he had asked Marcos the day before “if he were about to surprise us with a declaration of martial law.” The response was, Byroade wrote, “no, not under present circumstances. (Marcos) said he would not hesitate at all in doing so if the terrorists stepped up their activities further, and to a new stage. He said that if a part of Manila were burned, a top official of his Government, or foreign ambassador, assassinated or kidnapped, then he would act very promptly. He said that he questioned Communist capability to move things to such a stage just now.”

The ambush of Enrile’s convoy in San Juan on the night of September 22 would satisfy one of the listed circumstances although by then, it seemed just a violent flourish, an orgasmic bang that Marcos just needed to have to become a full-pledged dictator.

So the ambush was staged. Or not staged. Enrile had flip flopped on the subject.

Witness accounts later tended to support the view that it was a contrived move. In the 1985-86 issue of the Fookien Times Philippines Yearbook, Doreen G. Yu asked Enrile, “What about the incident of your alleged ambush that triggered the declaration of martial law?”

Enrile’s replied, “That was not my idea. In fact, when I was fired upon I just came from headquarters. I had transmitted to them the orders of the President declaring martial law. I was on my way home; martial law was already ongoing at this time, the operations were already on. Pres. Marcos simply used that to dramatize this, but that was not really necessary. Because he already decided to declare martial law long before that, because of what was happening in the country.”

In his memoir, Enrile insisted that the ambush was real and perpetrated by his unknown enemies.

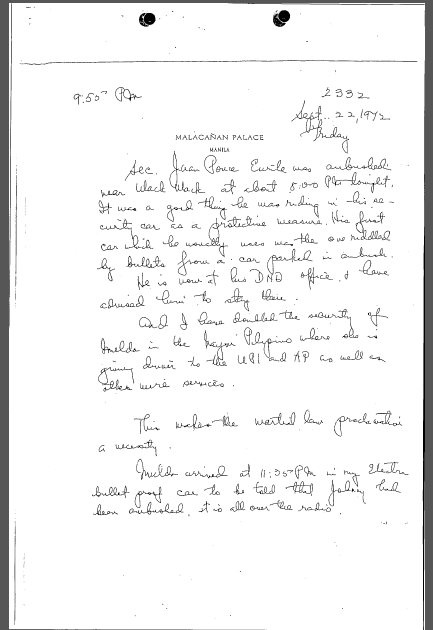

Excerpt from the diary of Ferdinand E. Marcos on September 22, 1972. From the Philippine Diary Project. Photo downloaded from Official Gazette.

Byroade’s effort to pierce Marcos’s secrecy yielded tangible result only on the evening of September 20, when he received a copy of Proclamation 1081. Raymond Bonner, in Waltzing with a Dictator, said that Marcos was betrayed by one of his “most trusted confidants.”

This was just two days after Marcos claimed in his diary on September 18 that they had finalized the plans for the proclamation of martial law, and that, after a four-hour meeting ending at 10 p.m. that day, the Rolex 12 minus Cojuangco and Gatan, settled on September 21 as the date of declaration “without any postponement.”

That an event that happened on September 18 made its way to a key legal document on martial law was proof that Marcos and his Rolex 12 would take advantage of any new developments to justify their move. The bombing at around 3:40 p.m. that day at the Quezon City Hall, where the Constitutional Convention did its work, was the latest event mentioned in Proclamation 1081. Writing in his diary around midnight, Marcos noted that the Quezon City Hall bombing was “the answer of the subversives to the raids on their headquarters in Manila, Quezon and Pasay…where about 48 were arrested.”

On the evening of September 20 and the day after, Byroade met with Marcos. In a September 21, 1972 telegram to the US State Department, the American diplomat said, “Marcos . . . had made no decision to move towards martial law, and he had never considered anything beyond that, such as military rule. He did admit, however, that planning for martial law was at an advanced state.” At the end of the telegram Byroade admitted that he was unsure if he “succeeded in at least postponing new developments.”

By September 21, the only seeming hindrance to Marcos’s plans was the fact that Congress was then in session. According to Enrile, “President Marcos was waiting for Congress to adjourn sine die . . . on Friday, September 22, 1972. It was for that reason that he had not acted on the declaration of martial law. President Marcos wanted Congress to adjourn first before he would proclaim martial law in the country. He wanted to avoid any resistance from Congress once he declared martial law in the country.”

But Congress did not adjourn. And Marcos was right in his sense that there could be resistance, but it was one that he managed to easily crush. “[A] few days after the declaration of martial law,” Petronilo Bn. Daroy wrote in a chapter of Dictatorship and Revolution: Roots of People’s Power, “a bipartisan caucus of congressmen and senators was held in the cell of Benigno Aquino, Jr., who had already been arrested and detained in Camp Crame. The caucus deliberated on convening a special session of Congress to declare Presidential Decree 1081, null and void. Aquino’s cell was, of course, bugged; the following day, soldiers secured the legislative building and dismantled the offices, carting away equipment, tables, and chairs. The legislative building was turned into the National Museum.”

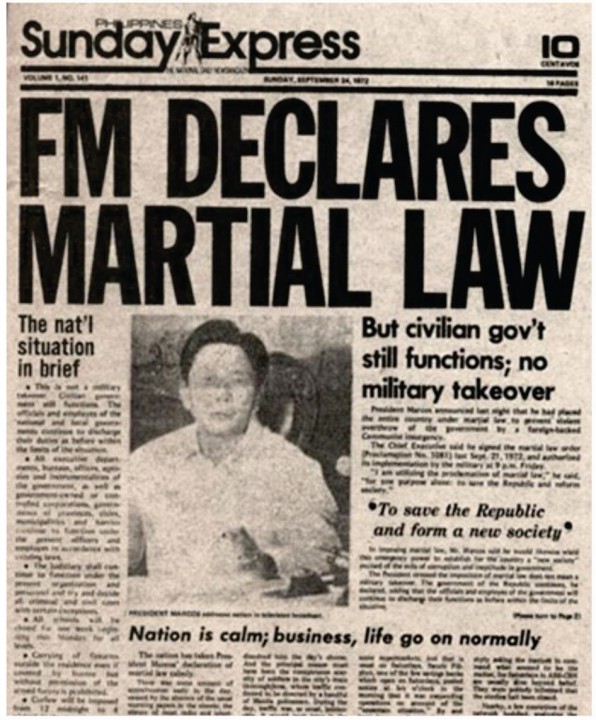

The Sunday edition of the Philippine Daily Express on September 24, 1972, the only newspaper published after the announcement of Martial Law on September 21, the evening prior. Photo downloaded from Wikipedia.

Since the start of 1972, talks of martial law abounded in the chattering class of Manila. It finally descended and Marcos exacted vengeance with the mass arrest of his enemies on the evening of September 22 until the early morning of the next day.

With his critics in jail and the press silenced, Marcos addressed the nation on radio and TV in the early evening of 23 September to state what was, by then, a matter of fact: martial law was in effect.

In the CIA’s daily brief for Nixon on 23 September 1972, there was almost a hint of admiration for what Marcos had done, that “Marcos carefully orchestrated the move well in advance.”

As Imelda exclaimed to Enrile when things settled down on the morning of September 23, “Ang dali pala ng martial law!”

(Joel F. Ariate Jr. and Miguel Paolo P. Reyes are researchers at the Third World Studies Center, College of Social Sciences and Philosophy, University of the Philippines Diliman. Larah Vinda Del Mundo provided research assistance. This piece is part of their on-going research program, the Marcos Regime Research.)