Five years in detention. Strict visitation restrictions. Violation of medical rights.

This has been journalist Frenchie Mae Cumpio’s life since her arrest for illegal possession of firearms and terrorism financing on February 7, 2020 in Tacloban City, Eastern Visayas.

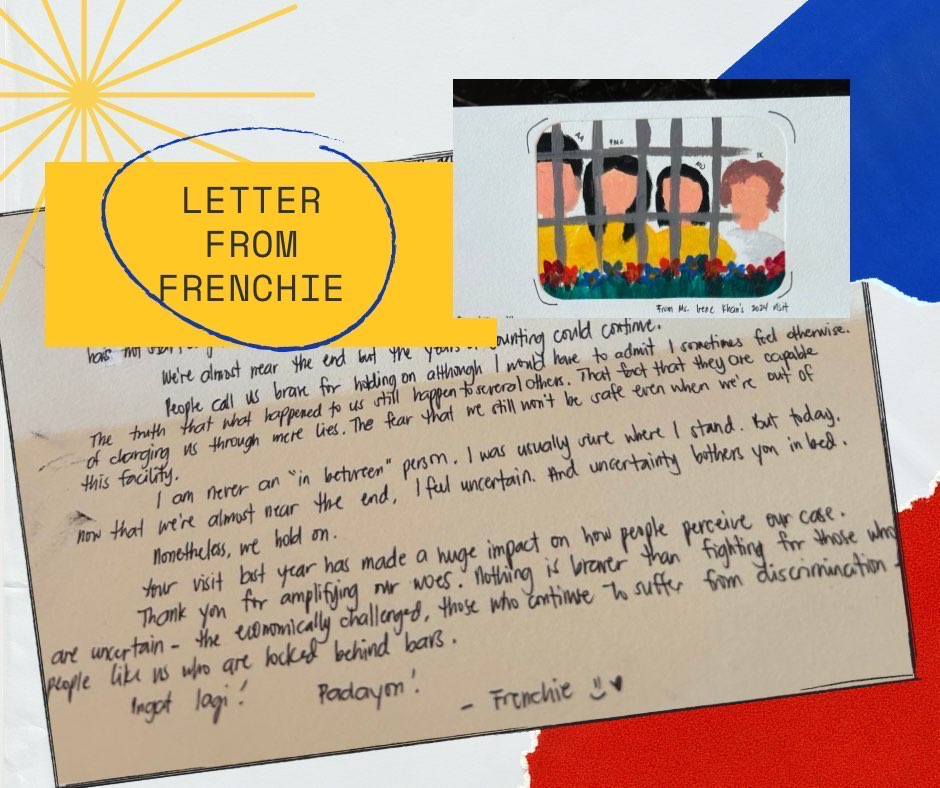

Last month, she managed to tell the world about her mental anguish and ordeal inside prison.

“People call us brave for holding on, although I would have to admit I sometimes feel otherwise. The truth that what happened to us still happens to several others. That fact that they are capable of charging us through mere lies. The fear that we still won’t be safe even when we’re out of this facility,” the detained journalist wrote in a letter to Irene Khan, United Nations Special Rapporteur.

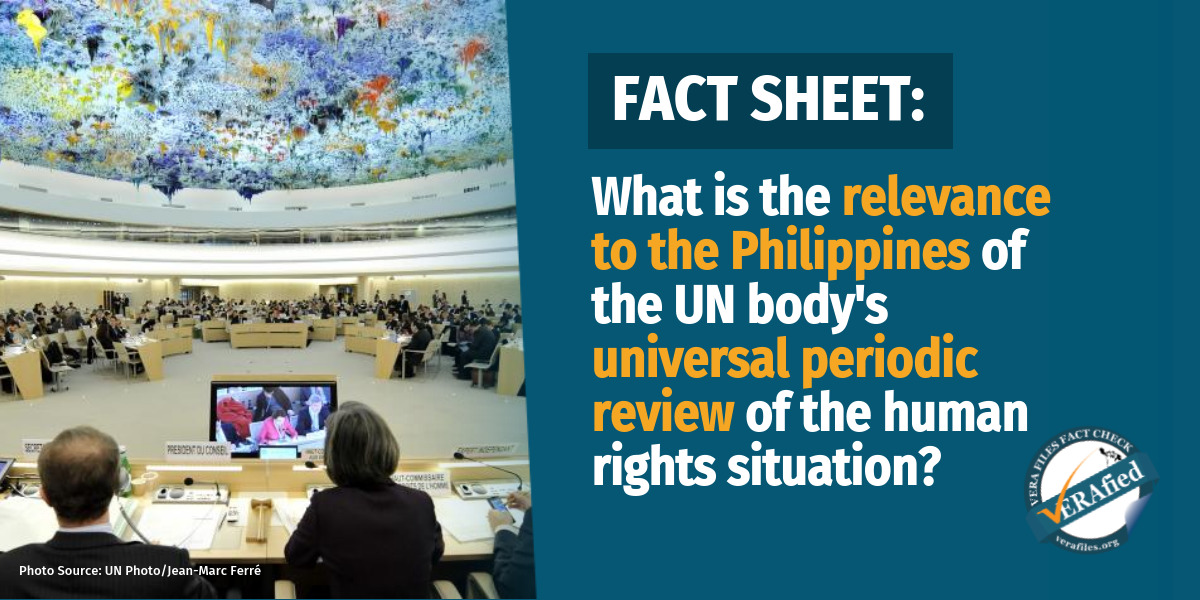

It was the first time that a direct message from Cumpio made it out of her detention cell and reached an international audience. The letter was presented before a global forum through Committee to Protect Journalists director Beh Lih Yi, who hand-carried it from the Philippines to Geneva.

Khan had shared it at a side event of the UN Human Rights Council on June 24 in Geneva. The UN Rapporteur, who went to the Tacloban City Jail in January 2024,

was the first and only international visitor allowed to visit Cumpio and the other detainees since their arrest.

“She managed to get a letter out to me. And you have to remember, of course, that anything she writes is checked before it gets out. Anything that we write to her is similarly checked before it gets to her,” Khan explained.

An investigative reporter covering mostly human rights abuses in law enforcement, Cumpio was charged along with co-accused Marielle Domequil and Alexander Philip Abingunia – both human rights defenders. Cumpio, now 26 years old, has denied the allegations, which remain unproven.

Beyond the five years in pre-trial detention, she could face up to 52 years in prison if found guilty of both charges.

Cumpio was arrested during a crackdown on journalists and activists in 2020, which was marked by raids where authorities would allegedly find explosives after presenting search warrants.

As a result of her 2024 jail visit, Khan criticized the Philippine government for the delay in handling the case, calling it an “unjustifiably long pre-trial detention.”

During her meeting with government authorities on Feb. 1, 2024, she told them that the case against Cumpio and her co-accused “reflect the human cost of ‘red-tagging’ and underscores procedural flaws that have limited their recourse.”

It was only last year that Cumpio’s trial started at the Tacloban Regional Trial Court where she and her co-accused were finally allowed to take the witness stand. They completed giving their testimony just this March.

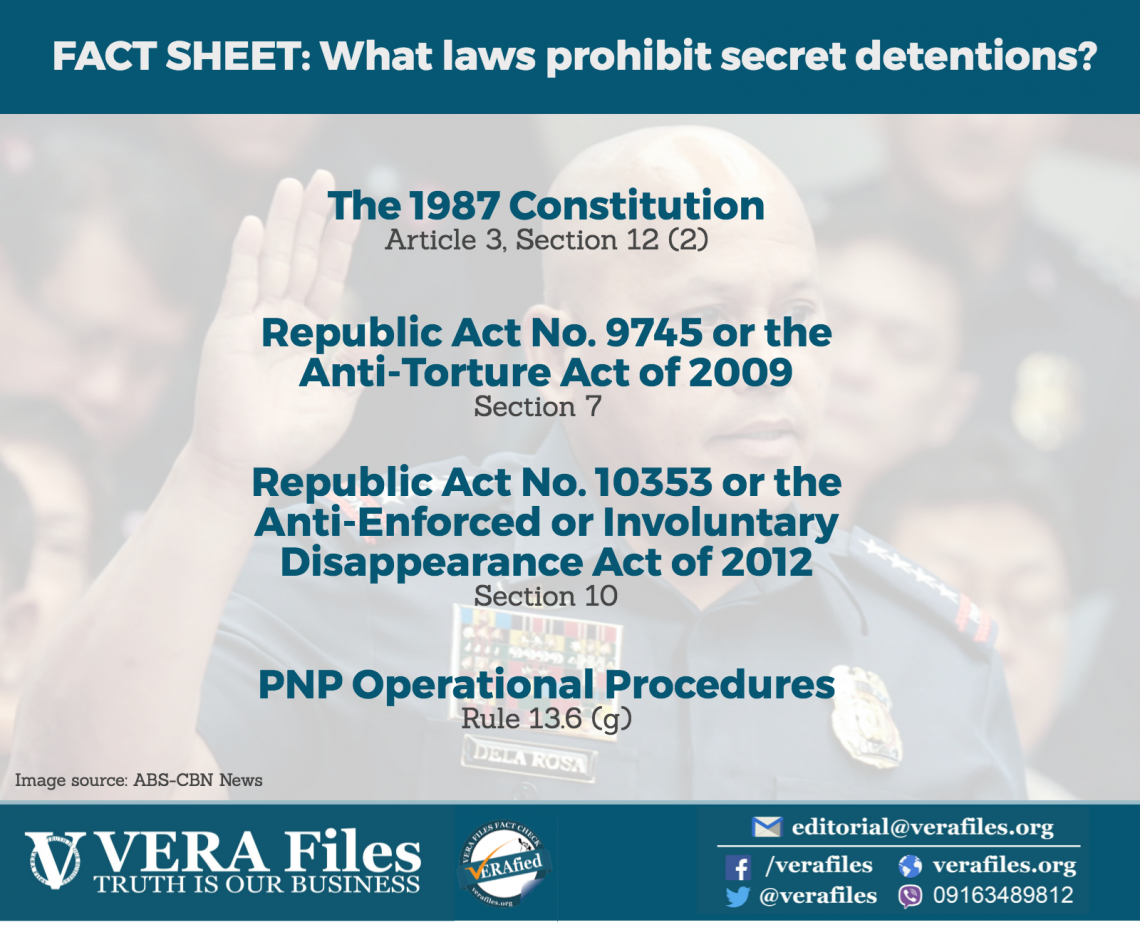

The broadcast journalist’s legal team noted multiple violations of constitutional rights when Cumpio and the others were arrested, including the failure of law enforcers to identify themselves or present a warrant when they raided the staff house where Cumpio and the others were staying.

In her narration, Cumpio said she was subjected to months of surveillance and harassment prior to her arrest. She recalled in detail how police officers kicked open the door of the room where she and Domequil were sleeping and ordered them to lie face down on the ground.

They were dragged outside and when they were later brought back, they saw guns and other contraband, including money, on their beds and around the room. The Anti-Money Laundering Council accused them of planning to use the P557,360 seized in the raid to fund operations of the New People’s Army.

“At first, it felt like I didn’t really have anything to say. How do we even combat a well orchestrated lie? A story that’s so absurd that if this was a class debate you wouldn’t even try to rebut,” Cumpio wrote to Khan. “But after my testimony, I realized I still had a lot to say that this more than five years of detention is robbing us of so many things. Time, family, dreams, plans, future.”

No visitors allowed

Cumpio and her co-accused have also been subjected to strict visitation restrictions and recent attempts to see them have been unsuccessful.

In a light moment, Khan shared that she received gifts from the three detainees during her visit.

“They had baked cakes for me. And it had given them joy to be able to do that because they didn’t have any visitors,” she recounted.

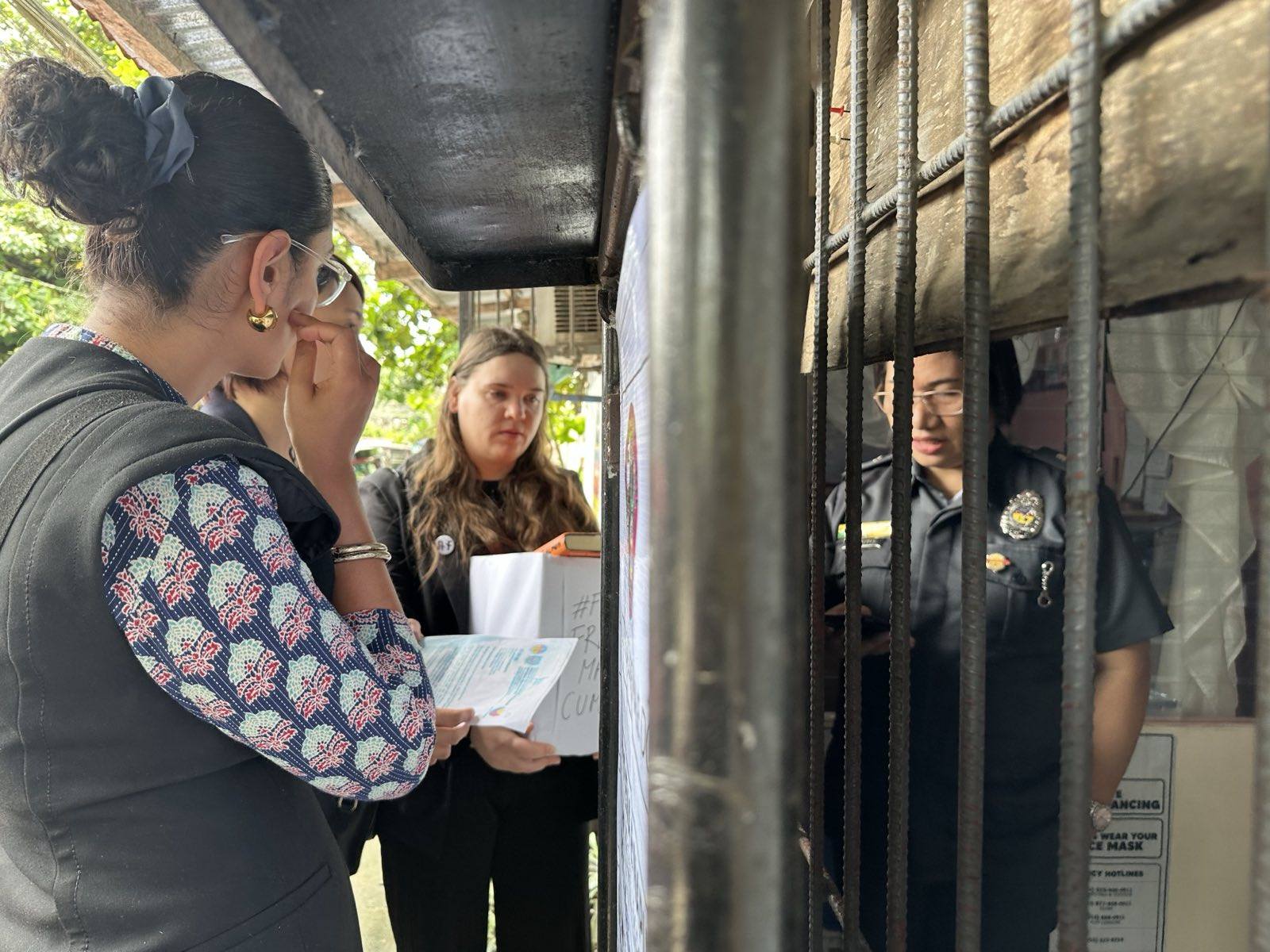

On June 16, members of the #FreeFrenchieMaeCumpio coalition were denied a visit despite submitting an official request to the Bureau of Jail Management and Penology a month before.

After lengthy negotiation, the delegation was finally allowed to briefly meet with Cumpio — from behind three layers of prison bars. They were only permitted to give her a handwritten letter and a package containing medication and other essentials.

Cumpio had been suffering from respiratory problems but had not been provided a “comprehensive medical examination” amid delays in access to proper healthcare, according to her mother and lawyers that met with the coalition.

The Philippine Press Institute denounced these continued restrictions and violations of medical rights.

“Such treatment undermines due process and exposes a callous disregard for press freedom. Jail authorities must be held accountable for these violations, and the government must act to end Frenchie Mae Cumpio’s unjust detention,” the group said in a statement.

Legal limbo

Despite Khan’s report, the government has pushed back and insisted that the arrest of Cumpio and her colleagues was lawful.

In its comments included in the report, the government argued that the cases are being afforded due process and denied that the charges consisted of “red-tagging.”

It stressed that the law applies to everyone regardless of profession and advocacy in the name of democracy, adding that those accused have access to legal remedies if they feel their rights have been violated.

Cumpio is only one of many that are stuck in justice limbo.

Karapatan Secretary General Cristina Palabay noted that some three million individuals faced red-tagging under the current administration. One of the most recent was Felipe Levy Gelle who was arrested on June 24 in Bacolod City with the same terror financing charges as Cumpio.

“Frenchie endures a trumped-up terrorism financing case and there have been 166 victims of arbitrary detention, designation, complaints, and charges of counterterrorism laws. And 45 of them, including Frenchie, remain in jail,” she noted.

The persistence of such cases was also raised by Amnesty International Philippines’ Renchillina Joy Supan, who said that the change in administrations did not improve the state of free speech in the country as civic spaces remain threatened by the National Task Force to End Local Communist Armed Conflict (NTF-ELCAC).

“Freedom of expression in the Philippines, the right to peacefully assemble, and our civic spaces remain under intentional and violent threat driven by the still existing instrument from the former President Duterte’s administration and the severe lack of political will to dismantle these structures and install genuine protection for human rights defenders, especially for children and young activists like us,” the researcher pointed out.

President Ferdinand R. Marcos Jr. has previously stated that the NTF-ELCAC will remain in place to reflect the government’s commitment to its anti-insurgency campaign.

Another form of torture

In the June 26 celebration of International Day in Support of Victims of Torture, Karapatan reported that there are 750 political prisoners in the Philippines to date and the number is increasing annually.

Noting that around a hundred of these detainees suffer from sickness while 106 are elderly, Karapatan described their situation as an indirect form of torture as it called for their release.

“Nagsisiksikan sila na parang sardinas sa maiinit at maruruming selda. Parang kanin-baboy ang pagkain nila. Walang maayos na akses sa malinis na tubig at palikuran. Dahil dito, madaling dapuan ng sakit ang mga bilanggo at ang mga dati nang may sakit ay lumalala ang kalagayan, lalupa’t wala silang natatanggap na maayos na serbisyong medikal sa kulungan.

(They are crammed like sardines in hot and filthy cells. Their food resembles what are fed to pigs. They don’t have proper access to clean water or toilets. Because of this, they easily get sick. Those who are already sick become more ill, especially because they do not receive medical treatment in prison),” it added.

(The author is a journalism student at the UP College of Mass Communication and is doing her internship with VERA Files.)