The Philippines’ human rights records will be scrutinized for the fourth time in a new cycle of the universal periodic review (UPR) of the United Nations (UN) Human Rights Council on Monday, Nov. 14.

A working group under the UN Human Rights Council will conduct the UPR, a UN procedure mandating the participation of all 193 member states.

What is UPR and its relevance to improving the human rights situation in the country? Here are five things you should know:

1. What is UPR?

The UPR is a mechanism established in March 2006 when the UN General Assembly (UNGA) adopted a resolution founding the Human Rights Council. The UNGA tasked the council to conduct the UPR through an interactive dialogue with the full involvement of a country under review, with consideration on its capacity-building needs.

The Human Rights Council describes the UPR as a “unique process” and the only “mechanism of [its] kind [that] exists” that provides opportunities for each of the 193 UN member states to report their actions on improving human rights situations in their countries and overcoming challenges “to the enjoyment of human rights.” It includes sharing of best human rights practices around the globe.

The council said UPR’s ultimate goal is to improve the human rights situation in every UN member state “with significant consequences for people around the globe.”

The UPR seeks to provide support for the promotion and protection of human rights in member states, and encourage full cooperation and engagement with the Human Rights Council, UN Office of the Commissioner on Human Rights (OHCHR) and other human rights bodies.

2. When is the UPR conducted?

The Human Rights Council follows a cycle that spans four-and-a-half years within which all UN member states undergo a periodic review of their human rights records. A working group mainly consisting of 47 member states of the council convenes three two-week sessions per year or a total of 14 sessions in a review cycle.

Since 2007, the council has conducted three UPR cycles. Its fourth cycle began on Nov. 7, when the 41st session of the UPR working group opened, and will end in February 2027.

The Philippines had its first, second and third UPR reviews in April 2008, May 2012 and May 2017, respectively. The fourth review will be on Nov. 14, from 4 p.m. to 7:30 p.m. (9 a.m. to 12:30 p.m., Geneva time), making the Philippines among the first batch of 14 countries to undergo the new cycle at the headquarters of the Human Rights Council in Switzerland.

3. How is the UPR conducted?

Each meeting for a periodic review is conducted for three and one-half hours, with an additional half-hour devoted for each country to adopt the recommendations put forward by the UPR working group and observer states. Groups of three country representatives, who are called “troikas” or rapporteurs, will facilitate each UPR session.

[infogram id=”1pr9lglk76m3prtg19mkqvmrrramqedpjqv?live”]

In examining the human rights record of a country, the working group scrutinizes the reports submitted by the state itself, including the steps taken to address the recommendations and other challenges raised during the previous review cycles. It will assess the country’s compliance with its human rights obligations under the UN Charter, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, voluntary pledges and commitments, such as implementation of national human rights policies, and applicable international humanitarian law.

The group will use as a basis for its review the reports submitted by independent UN human rights experts and groups (also known as the Special Procedures), UN entities, and stakeholders such as national human rights institutions, i.e. the Philippine Commission on Human Rights.

[infogram id=”1p6zd9rplwgkejf5lwgpp1xv33i36dkm032?live”]

At the end of the review session, the troikas will prepare a report containing a summary of the interactive dialogue such as the questions, comments and recommendations addressed to the state under review. The working group is scheduled to adopt the recommendations made to the Philippines on Nov. 16.

The final outcome of the periodic review on the Philippines and 13 other countries during the 41st session will be adopted by the plenary of the Human Rights Council during its 52nd regular session in March 2023.

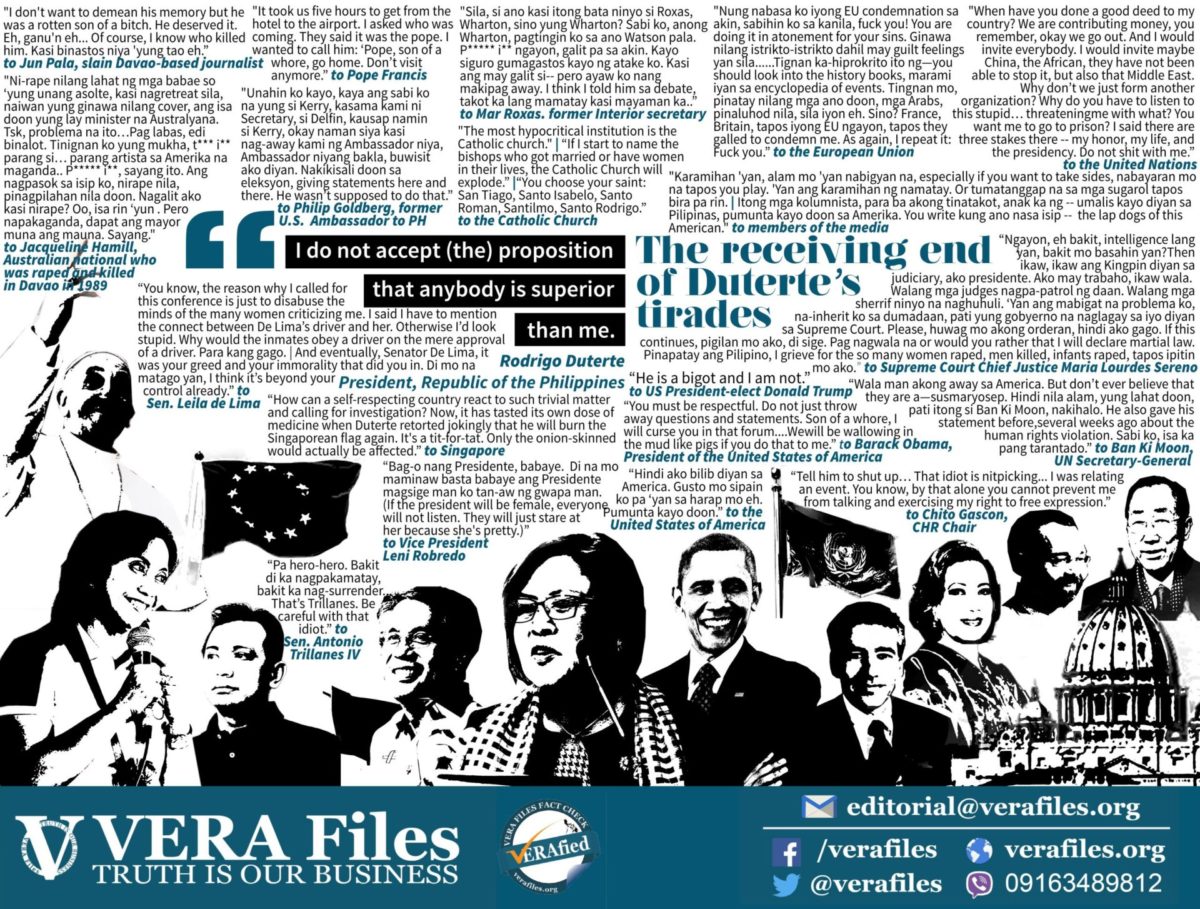

4. What are the human rights issues to be raised in the UPR session of the Philippines?

A set of reports uploaded on the UPR webpage for the Philippines lists down some issues and concerns on the human rights situation in the country raised by the OHCHR and over 50 local and foreign civil society groups.

In its 12-page report, the OHCHR cited the continued killings of suspected drug offenders and human rights defenders despite the COVID-19 pandemic and the persistence of impunity and “practical obstacles” in obtaining justice, among other issues.

Meanwhile, the Center for Trade Union and Human Rights, Women Workers in Struggle for Employment, Empowerment and Emancipation (Women WISE3) and May First Movement reported, through a joint submission to the OHCHR, several work-related issues such as the continuous practice of contractualization in the Philippines.

Several UN member states, such as Canada and Belgium, have submitted questions in advance for the Philippines. For example, the United States asked the Philippine government what it is doing to address the continued reports of harassment and threats of violence against journalists and media workers and the red-tagging of human rights defenders. It expressed concern over the “prolonged detention” of former senator Leila De Lima.

5. What’s next after the UPR session?

The Human Rights Council said all countries are accountable for the progress or failure in implementing the recommendations contained in the final outcome of the periodic review. Following the mechanism of the UPR, the council may again ask the member states on the improvement of their human rights records in the next review cycle.

The council added that the international community will assist in the implementation of the recommendations and conclusions regarding capacity-building and technical assistance, in consultation with the country concerned. It may address cases in which states are not “co-operating.”

Have you seen any dubious claims, photos, memes, or online posts that you want us to verify? Fill out this reader request form.

Sources

United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights official website, Universal Periodic Review – Philippines, Accessed Nov. 11, 2022

United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights official website, Basic facts about the UPR, Accessed Nov. 11, 2022

United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights official website, Universal Periodic Review Working Group to commence fourth cycle with holding of its forty-first session from 7 to 18 November 2022, Nov. 2, 2022

United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights official website, The Philippines’ human rights record to be examined by Universal Periodic Review, Nov. 9, 2022

United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights extranet, Universal Periodic Review chart, Accessed Nov. 10, 2022

United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights extranet, Universal Periodic Review chart, Accessed Nov. 10, 2022

United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights official website, Compilation of UN information, Accessed Nov. 12, 2022

United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights official website, Summary of stakeholders’ information, Accessed Nov. 12, 2022

United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights official website, First batch of questions by UN member states, Accessed Nov. 12, 2022

United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights official website, UN Photo/Jean-Marc Ferré, Accessed Nov. 12, 2022

United Nations Office of the high Commissioner for Human Rights official website, The universal review process, Accessed Nov. 12, 2022

(Guided by the code of principles of the International Fact-Checking Network at Poynter, VERA Files tracks the false claims, flip-flops, misleading statements of public officials and figures, and debunks them with factual evidence. Find out more about this initiative and our methodology.)