By ELLEN T. TORDESILLAS

TWO things came to our mind when we read about President Duterte’s threat of suspending the writ of habeas corpus if lawlessness in Mindanao worsens.

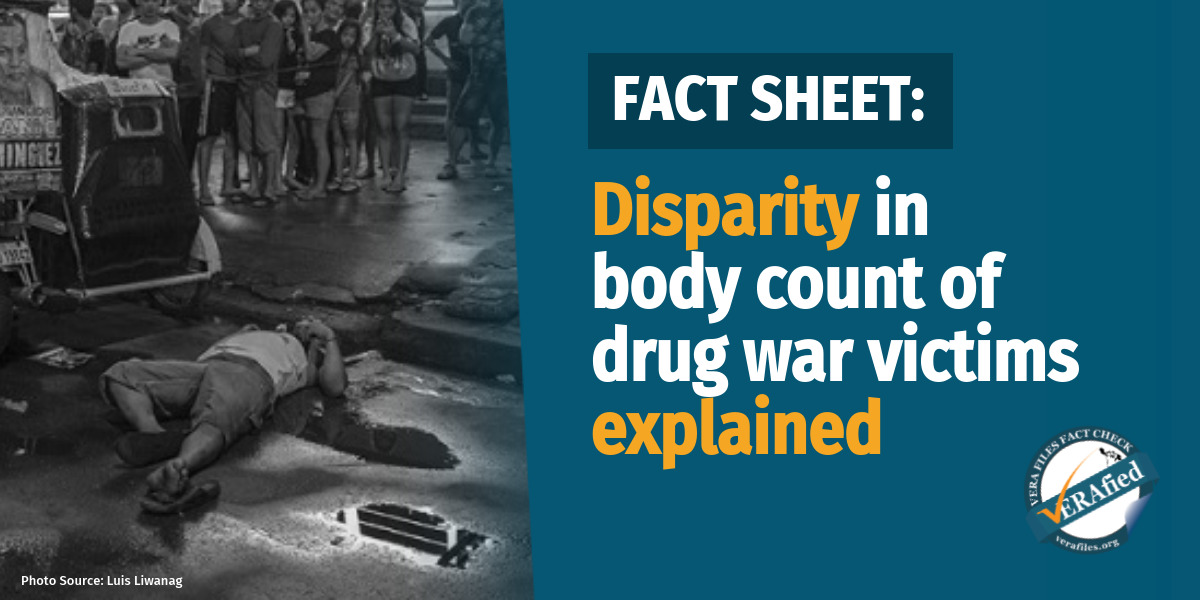

Number one, his “Kill, Kill” strategy in eradicating the illegal drug problem is not solving the problem despite 4,000 killed.

Number two, the public has been desensitized by all these killings. Duterte knows the public won’t might if he takes his violation of human rights a notch higher.

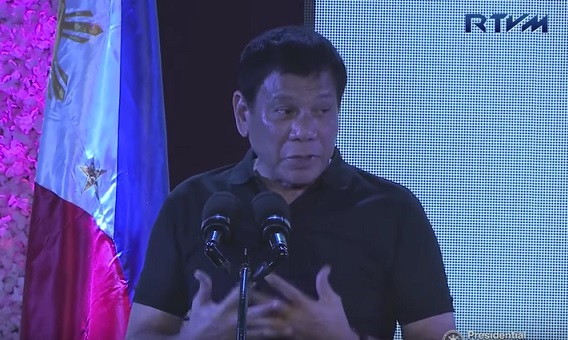

In a speech at the launching of the Pilipinong May Puso Foundation in Davao City on Friday, he made his usual narration of the gravity of the illegal drug problem in the country. This time, he added the “rebellion” in Mindanao (“Grabe ang bakbakan…”).

“At kung magkalat itong still lawlessness, I might be forced to..” he paused saying it is not something he likes; “Ayaw ko, ayaw ko. Warning ko lang sa kanila ‘yan, ayaw ko kasi hindi maganda.”

But he still dropped the dreaded phrase: “But if you force my hand into it, I will declare the suspension of the writ of habeas corpus.”

What is suspension of the writ of habeas corpus?

Article VII, Sec. 18 of the Philippine Constitution states that, “In case of invasion or rebellion, when the public safety requires it, he (the President) may for a period not exceeding 60 days suspend the writ of habeas corpus or place the Philippines or any part of it under martial law.”

Duterte emphatically said, “Not martial law. Wala akong balak sa pulitika. But I will kasi wala akong remedy.”

Habeas corpus is the power of the court to require the state to produce the body.

With the suspension of the writ of habeas corpus, military and police authorities can make warrantless arrest. When they pick you up and bring you to a place only they know where they can torture you, your family cannot go to the court to ask the government to produce your body. You may survive or you may die.

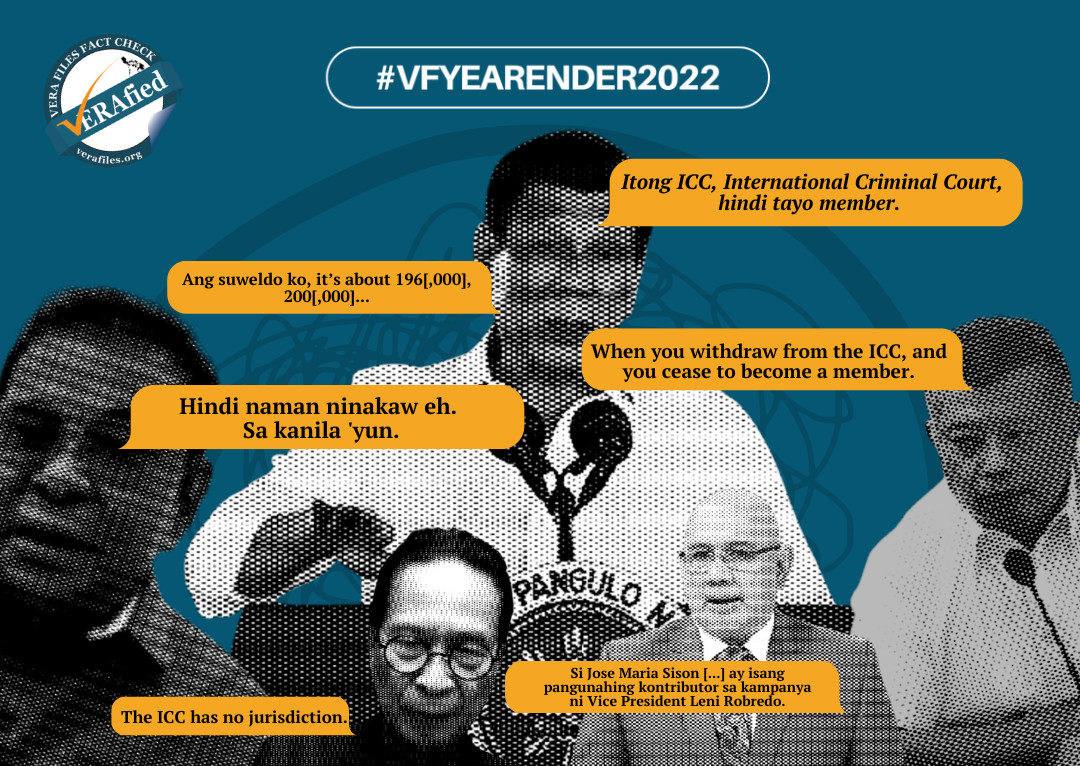

That was what happened when the late dictator Ferdinand E. Marcos suspended the writ of habeas corpus on Aug. 21, 1971 after the bombing of the Liberal Party rally at Plaza Miranda (which later on was exposed to be the handiwork of the CPP’s Joma Sison.).

One year after, Marcos declared Martial Law.

Amnesty International estimates there were some 3,240 killed during Martial Law. Some 70,000 were imprisoned and 34,000 were tortured.

The lack of a loud outcry against Duterte’s warning is an encouragement for Duterte to push through with his plans to suspend the writ of habeas corpus.

Last month, in a seminar on the Rule of Law, lawyer Chel Diokno, son of the distinguished Jose W. Diokno said we are witnessing today hundreds if not thousands of people taking the law into their own hands, dispensing justice from the barrels of their guns, deciding who are guilty and who are not, who deserves to die and who deserves to live and using fear and violence to enforce the law.

“The very same fear and violence that the martial law regime used so effectively four decades ago. The labels have changed, but the tactics are the same, “Diokno said.

He quoted from his father’s writings, “A Nation for our Children “:

“Fear need not be of communists: it may be of terrorists, gangsters or mere non-conformists [or even drug addicts and pushers]. Whatever its cause, fear—carefully nurtured by the establishment—hardens into the belief that communists, terrorists, dissenters, anarchists—call them what you will—have forfeited their humanity, and so have forfeited their rights.

“Seen as posing extraordinary dangers, they justify extraordinary remedies: national defense becomes national security; military values infiltrate society; the inevitable result is military rule or some other variant of dictatorship; and in the process, human rights blur and evanesce.”

“Fear is a powerful motive, but an unreliable guide. It can create evils more monstrous that those it seeks to avoid. It can kill freedom while trying to preserve it.”

Those words are as relevant as they were written more than three decades ago.