There is no news on the progress of House Bill (HB) No. 7758, or the proposed Menstrual Leave Act, which was filed by Gabriela Rep. Arlene Brosas in March.

HB 7758 seeks to grant working women two-day menstrual leave with full pay. A similar bill, HB 6728 filed by Cotabato Rep. Samantha Santos in January, call for only 50-percent remuneration.

The truculent resistance that met HB 7758 was sad and surprising. Many people were up in arms against a proposal to alleviate the menstrual pains and related conditions that women, the formidable half of the Philippine labor force, experience regularly. But why?

The provincial governments of La Union and Aklan have already implemented similar measures. In La Union, female government employees were granted a monthly “menstruation privilege” — two days of working from home during their period after Gov. Rafy Ortega-David signed Executive Order No. 25 in October 2022, per cnnphilippines.com. In Tangalan, Aklan, female employees have also been enjoying a two-day menstrual work-from-home benefit since Ordinance 2022-214 was signed by Vice Mayor Gene Fuentes in November 2022, as reported by rappler.com.

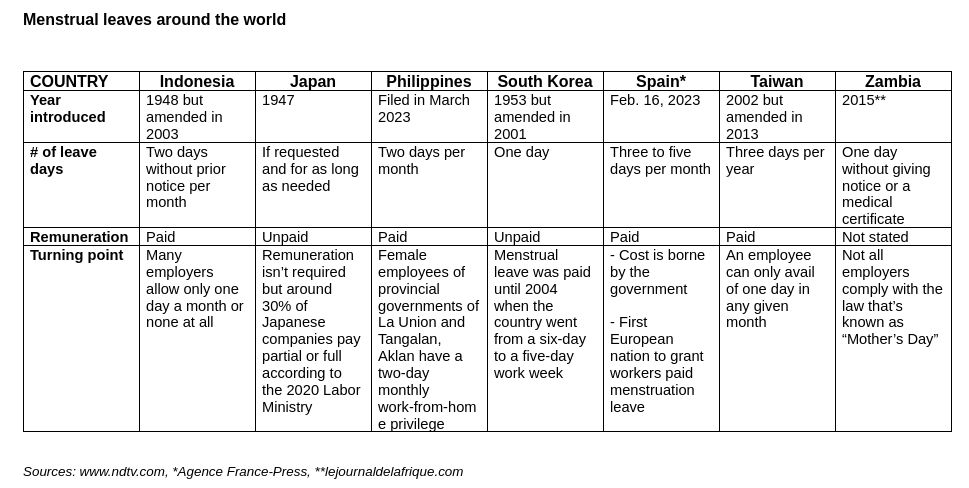

Indonesia, Japan, South Korea, Spain, Taiwan and Zambia have enacted bills similar to HB 7758. Ratifying it is not impossible, but it’ll be a herculean task. The problem lies in the prevailing view of women as, in the words of French feminist Simone de Beauvoir, the “second sex,” the inferior in the man/woman binary.

Order of things

The age-old man/woman binary presupposes the former as dominant and therefore prioritized — a view that still holds strong despite the great advances in science and technology. It’s indicative of how women’s “acceptability” is mere tokenism, necessitating them to constantly toe the line to maintain the order of things. Beauty and femininity are upheld above intellect; matters like menstruation are not discussed openly and factually and, worse, used against women in all aspects of their lives.

As a teenager in Indonesia, Elisabeth Puella was told that monthly periods were dirty. This made her and her generation “afraid to do the usual activities on the first day of menstruation,” says Puella, a biology teacher at Global Prestasi School, in an email interview. They also had to live with such yarns as avoiding eating meat and not washing their hair while bathing during their monthly period.

Longtime educator Katherine Edwin had a similar experience growing up in Singapore. She recalls the many “rules” to follow when a girl or woman is menstruating, such as avoiding religious places because she is “unclean,” and staying in her room, keeping away from the men in the house.

And talking about monthly periods — euphemistically called “Auntie visiting” — was taboo, except when she was with her girlfriends, Edwin says.

Fast and furious

Negative reactions to Brosas’ HB 7758 came fast and furious. Waxing sarcastic, former senator and presidential candidate Panfilo “Ping” Lacson tweeted that the next “legislative measure [to] be filed [would mandate] menopause and andropause allowances, to increase the testosterone levels of workers.” He also warned that menstrual leaves might lead to “layoffs or even the closing of some factories that may not have the wherewithal to cope with the burden of complying with all these privileges.”

Lacson’s sentiment was shared by Sergio Ortiz-Luis Jr., president of the Employers Confederation of the Philippines, who cautioned against “not overdoing it.” Ortiz-Luis stressed that the additional 24 days of leave in a year would be an extra financial burden to micro and small businesses, as reported by inquirer.net. He pointed out that many employees avoid using their wellness leave — comparable to a menstrual leave — so they could convert these to cash at the end of the year.

Similarly, entrepreneur Kelie Ko, president of the Mandaue City Chamber of Commerce and Industry, was reported as lamenting the potential burden that menstrual leaves would impose on businesses, and highlighting the need for “checks and balances to prevent abuse, as not all women have the same level of reproductive challenges.”

Fighting stance

Not everyone took the negative comments to HB 7758 lightly.

Mela Habijan, Miss Trans Global 2020, didn’t mince her words on Instagram: “Sen. Ping needs to strip off his toxic patriarchal masculinity because it’s blinding. It hinders empathy and cultivates ignorance…A woman (or any person) in pain won’t be productive and functional… Menstrual leave leverage health equity for women and people who menstruate.”

Triathlete Emma Pallant-Browne responded with powerful equanimity to people critiquing the photo she shared of her bleeding through her swimsuit (she was running in the PTO European Open Triathlon in Ibiza, Spain, at that time, according to tyla.official).

Said Pallant Browne: “Thanks for caring but definitely something I’m not shy to talk about because it’s the reality of females in sports. My period comes over a month in between and there will be one day where it’s super heavy…No matter what tampon I have experimented with, for anything over three hours it’s too heavy. So I, just as someone might get gut issues in a race…have to suck it up and give what I have, and not be afraid to talk to women who have the same problem.”

Taboo or no taboo, environmental scientist Giselle Goloy is adamant about talking about menstruation: “Half of the population goes through [menstruation), but we hardly talk about it because we — men and women — think it’s gross. We forget to credit the menstrual cycle for us being here. It’s nothing to be ashamed of,” says the Filipino Australian in an email interview.

Goloy has dealt repeatedly with severe headaches and cramps as well as body pains during her monthly period, rendering her short-tempered, aggressive, and lethargic — a condition that, she says, “sometimes appears like mild depression.” She goes on to say that menstrual health isn’t only about periods, but also about conditions like endometriosis and polycystic ovarian syndrome “which can be debilitating and difficult to go through.”

Even TV dramas are doing their part in bringing menstruation into the open. In “Hidden Love,” a Chinese drama series, Duan Jiaxu (Chen Zheyuan) helps Sang Zhi (Zhao Lusi), the younger sister of his college buddy, through her first period. Jiaxu alerts his buddy and they go to buy pads for her, with Jiaxu throwing in a new skirt to replace her stained one. The Korean drama series “Love in Contract” has Jung Ji-ho (Go Kyung-pyo) discreetly handing Choi Sang-eun (Park Min-young) a pad when she gets her period in the middle of a golf game.

Allies

Certain men have shown support for menstrual health, like fitness trainer-hybrid athlete Kirk Bondad. The Filipino German has told other people on Instagram not “to get awkward when someone talks about menstruation because…it’s a normal process… Menstruation is a totally normal topic and women shouldn’t feel embarrassed to talk about it.”

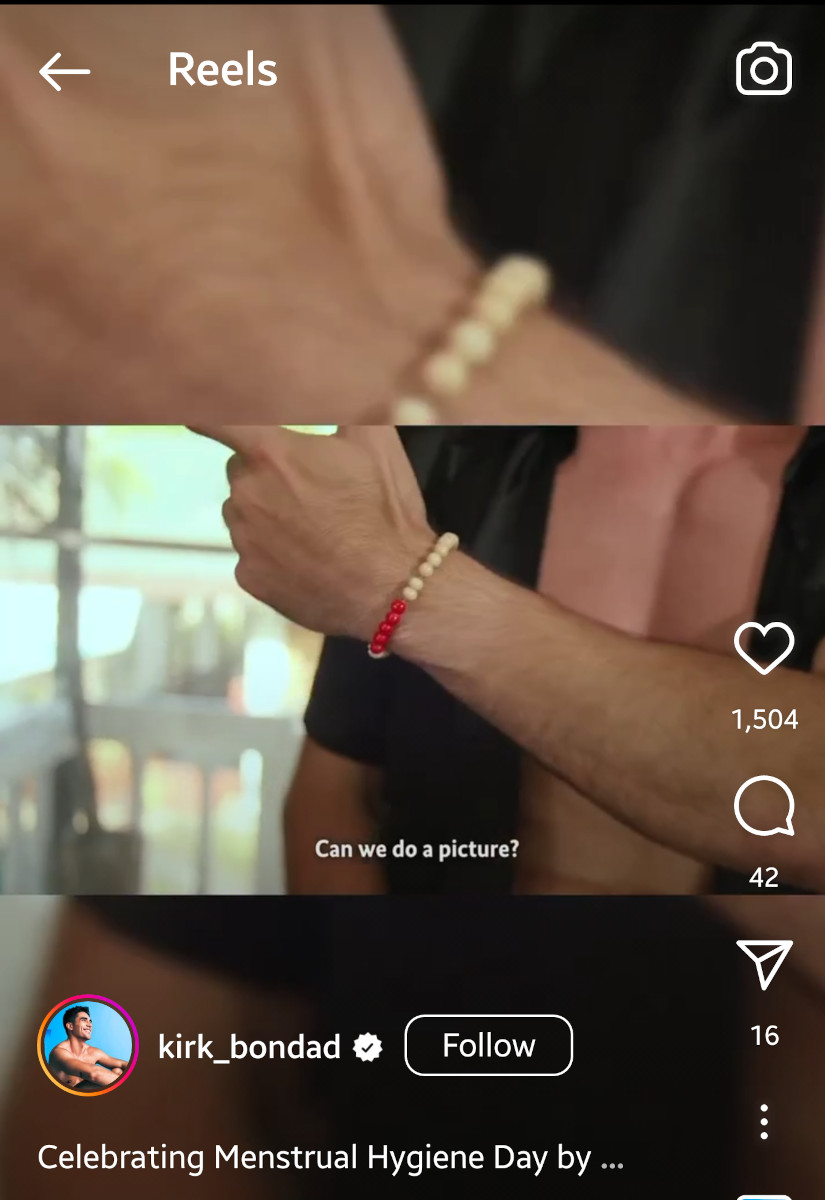

Kirk Bondad wears the menstruation bracelet, the global symbol for menstruation, to help stop the stigma. (Source: @kirk_bondad)

Bondad is the Goodwill Ambassador for Menstrual Health and Hygiene in the Philippines, a social media campaign funded by the German government and in partnership with the University of the Philippines’ Center for Women’s and Gender Studies. Together with co-ambassador Kathleen Paton, Miss Eco International 2022, he has appeared in advocacy videos and engaged in activities breaking menstruation taboos and promoting gender equality.

He has strengthened his commitment by wearing the menstruation bracelet, the global symbol for menstruation, without qualms, in hopes of “[encouraging] more people, even boys, to participate” in normalizing the topic.

In India, the catalyst in prioritizing menstruation in lawyer Thorsten Kiefer’s work was his first sanitation and hygiene project — Clean India March (CIM) — in 2012.

Kiefer was in a standoff with then Rural Development Minister Jairam Ramesh, who had hedged his bets in supporting CIM. As Kiefer told Maria Hawranek, of kulczyfoundation.org.pl in an interview, the minister’s assistant called him to say that he, Kiefer, couldn’t talk about menstruation issues at the press conference because “while the minister was happy to be a toilet champion, the whole menstruation thing was too much.”

The impasse was broken when Ramesh finally gave his approval for CIM. After Ramesh’s visit to CIM’s menstruation information tent, which had long queues of women and girls seeking entrance, “menstrual issues [became] part of India’s water and sanitation policy six months later.”

Circumspection

Dr. Ramon Eduardo Gustilo Villasor, a counseling and sports psychologist at Makati Medical Center, remains circumspect about menstruation. In a Zoom interview, he says his experiences at work have had him “hearing I don’t feel well today because it’s the time of the month’ said in passing…in a seminar or a closed group as an explanation for why they wouldn’t be at their best… That’s one of the things I can ask, but it’s not meant to infringe on anybody’s privacy.”

He continues: “We’re living in a society (that’s] now open to talking about the issue [compared] probably to 20 years ago. But it would still depend on the circumstances that they would share. Conversations about it would understandably happen between a couple, not necessarily a married me, or with a group of women. For it to be part of a regular conversation depends on the closeness of the individuals and its relevance. It can’t just come out of nowhere.”

But here and elsewhere, communities have been organized to end period stigma, combat misinformation, and alleviate period poverty (or the lack of access to menstrual products, education, etc.). One is Share the Dignity (www.sharethedignity.org.au) that the Sydney-based Goloy actively supports.

Share the Dignity is a women’s charity in Australia that gives women and girls period products. It has donated more than four million period products, shipped more than 238,000 period products to remote indigenous communities, and put up 424 Dignity machines disposing free pads and tampons. It also helps those “experiencing homelessness, fleeing domestic violence, or doing it tough,” and in ending the shame and stigma around periods and period poverty in Australia.

“As I understand, free pads and tampons are available in public schools in the state of Victoria,” says Goloy. “And I think Scotland is the first country in the world to provide free sanitary products to end period poverty. Period products aren’t cheap. This generation is probably better at shining a light on period poverty and finding innovative ways to tackle this while governments around the world are still playing catch up.” (Free period products are now available in schools in New Zealand, Zambia, several US states, and provinces in Canada, according to menstrualhygieneday.org.)

Share the Dignity’s mission is paralleled the Philippines by the We Bleed Red Movement (@webleedred.ph) founded in 2019 by Gianinna Czareena Chavez. The women-led online campaign has worked to remove period stigma, clarify period myths through healthy and open conversations, and advocate for menstrual equity, menstrual health and hygiene, and menstrual visibility in the country.

A huge part of its campaign is concentrated on its menstrual kit donation drive, implemented most recently in the aftermath of Typhoons “Egay” and “Falcon” because, as it said on its July 31 Instagram caption, “periods don’t stop for typhoons and calamities.” It turned over the collected kits to NGOS Angat Abra and Damayang Migrante.

To date, We Bleed Red has organized 24 donation drives and donated 5,000 menstrual kits in 28 locations nationwide.

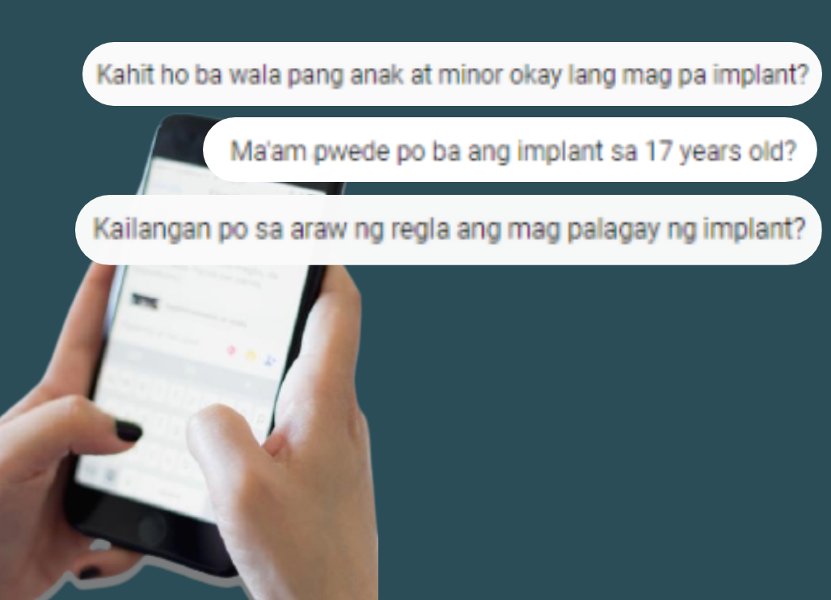

The Australian government and the Philippine education and health departments have reached digitally to help Filipino girls aged 10 to 19 with their periods through Oky Philippines, an app that tracks menstrual cycles, reported the Inquirer. The app is downloadable from Google Play Store and features a period countdown, “’daily cards’ to list moods etc., diary, daily quiz on menstrual health and sexual and reproductive rights, and information on menstruation, body, and health.”

Oky Philippines is based on Oky, a menstruation education and period tracker app developed by the United Nations Children’s Fund.

Open minds

The enactment of the proposed Menstrual Leave Act can be realized if rationality is cultivated putting a stop to patronizing views of menstruation and women. As it stands, menstrual health should be promoted just like any other health issue because “without menses there’s no life,” says the Singapore-based Edwin.

The Indonesian Puella is of the same mind, but widens the discussion scope to include environmental issues such as the use and disposal of menstrual pads.

Goloy is adamant that women be open to the subject. “They’re great at gaslighting themselves – ‘It’s just period pain, I should just suck it up and grow a pair.’ I’d like to see some men go through extremely painful dysmenorrhea and see who really needs to grow a pair,” she says.

Consequently, Goloy believes, men have to be more understanding. If that’s dovetailed with women’s openness, the idyllic situation “would make it feel less taboo to talk about something that’s completely natural,” she says. “It may also remove some of the guilt and doubt that [women] sometimes feel about asking for sick leave.”

For a civilized environment to exist, parents have an important role to play. They must set the tone for conversations around menstrual cycles, of making the uncomfortable comfortable. However, “[discussions shouldn’t] just be with their daughters, but also with their sons — that it’s not taboo and is nothing to be ashamed of or grossed out about,” Goloy points out.

Villasor shares Goloy’s view, stressing that initiating the talk is the parents’ responsibility: “It should never be delegated to the school. The discussion in the school should augment what the parents already had talked [to their children] about,” he says.

Engaging the typically hesitant or pugnacious Filipino men is a possibility. Villasor thinks they’d be assimilated if the community is fine with it, and “be cool about it unless someone in the group makes a big issue out of it.”

Bigger picture

Tellingly, women are still divided on the legalization of menstrual leaves. While Goloy sees an absolute need for it, Edwin and Puella find it unnecessary. Edwin argues that their mothers and grandmothers managed the “natural clockwork every month,” while Puella believes women can manage by “understanding menstrual health… [and] maintaining a healthy lifestyle” notwithstanding Indonesia’s menstrual bill.

The bigger picture is that, amid differences in opinion, menstrual leave is a vital piece in completing the menstruation jigsaw puzzle. Once completed, it will help protect women afflicted with debilitating menstrual pain and related conditions. It will help end period stigma and the isolation haunting girls at the start of their periods and, in certain cases, throughout their adult life. It will help break the view of women as the weak gender.

Most important, it will help change the one discussion of menstruation as “a woman’s issue” into “everyone’s issue.”