Adverse weather situation provided a face-saving exit for both the Philippines and China in the more than two-month standoff over Scarborough shoal, also referred to as Panatag shoal or Bajo de Masinloc by Filipinos and Huangyan island by the Chinese.

President Aquino said there would be no need to send back Philippine ships to Scarborough shoal if no vessel from other countries would be seen during aerial reconnaissance that the Philippine Air Force would be regularly doing.

But before that, careful not to be seen as the one who blinked first, Filipino and Chinese officials issued statements that were both conciliatory and contradictory.

The confusing statements were actually directed at their respective domestic audiences, agitated by nationalist rhetorics the governments also encouraged.

Last June 16, Department of Foreign Affairs issued a statement by Foreign Affairs Secretary Albert del Rosario announcing that “President Aquino ordered both our ships (Philippine Coast Guard and Bureau of Fisheries and Aquatic Resources) to return to port due to increasing bad weather. When weather improves, a re-evaluation will be made.”

At that time, typhoon “Butchoy” was heading towards the Philippines making the situation at sea extremely rough. Experienced seafarers attest that half a day in rough seas would cause even the most sturdy headaches and nausea.

China, which had announced a fishing ban mid-May having anticipated the big waves and the rains that come with the Southwest monsoon at this time of the year, issued a statement welcoming the Manila’s announced pull out: “We have noticed the withdrawal of government vessels by Philippine side. We hope this action will help ease the tensions,” said Zhang Hua, spokesperson of the Chinese Embassy in Manila.

There was no public announcement of an immediate reciprocal action from China. Behind the scenes, however, China told the Philippines that they were withdrawing two of their eight vessels in the area within 24 hours, which will be followed by two more the next day and more on the succeeding days until all their vessels are withdrawn.

Two days later, China announced that they were sending two ships to assist the more than 20 fishing boats in the disputed area that would be withdrawing because of bad weather.

A glitz occurred in the otherwise positive turn-of- events when DFA spokesman Raul Hernandez said that China’s announcement of a pullout was “consistent with our agreement with the Chinese government on withdrawal of all vessels from the shoal’s lagoon to defuse the tensions in the area.”

Chinese leadership, who had to deal with the hardline elements of their military, didn’t appreciate DFA’s statement which could give the impression that they were compromising their territorial claim. Hong Mei, spokesperson of China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs , expressed ignorance of the “agreement” Hernandez mentioned.

Hong advised “Philippine side” to “restrain their words and behavior and do workings conducive to the development of the bilateral relations” between the two countries.

Rather than focus on salvaging its pride, DFA should learn the wisdom shared by an Italian diplomat assigned in China, Danifele Vare: “Diplomacy is the art of letting someone else have your way.”

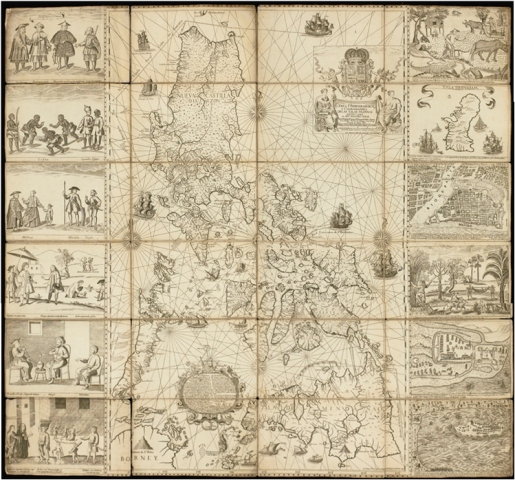

The two-month standoff started last April 10 when Philippine Navy’s BRP Gregorio del Pilar, the country’s lone modern naval patrol frigate acquired from the US last year, chanced upon eight Chinese fishing vessels in the Scarborough shoal while on its way to Northern Luzon as part of the contingency measures for North Korea’s rocket launch.

China, which also claims ownership of Scarborough shoal, sent its Marine Surveillance ships to prevent the arrest of their fishermen.

BRP Gregorio del Pilar had to immediately withdraw from the disputed shoal in accordance with the government policy of “white to white, gray to gray.” “White to white” means civilian ships are to deal only with civilian ships, in this case the Philippine Coast Guard to the Chinese Marine Surveillance. “Gray to gray” means navy to navy.

The incident, which was not actually new according to Philippine Navy logbooks, was raised to the highest level on the Philippine side with President Aquino himself issuing statements asserting the country’s sovereignty over the shoal 124 nautical miles off Zambales province.

All throughout the verbal fireworks, the highest Chinese official issuing statements was the spokesman of the foreign ministry. No statement was ever attributed to President Hu Jintao or Premier Wen Jiabao. Not even to its foreign minister, Yang Jiechi.

That’s something that Aquino and Del Rosario should take note of.

The standoff had hreatened to spill over to trade and tourism when China tightened the regulation on banana imports from the Philippines and several Chinese tour groups cancelled visits to the Philippines.

Discussions of Philippine and Chinese officials clarified that Filipino exporters were not exactly blameless sending insect-infested bananas to China.

Tour cancellations were caused by tour groups getting nervous seeing demonstrators in front of Chinese embassies in Manila and the United states denouncing China’s “bullying” of the Philippines. The rallies have stopped and Chinese tourists are seen again in Boracay and other resorts in the country.

The tension in Scarborough shoal has, in the meantime, abated. But there’s no assurance that China will not return and attempt to fortify its claim just like what it did in Mischief Reef in the Spratlys.

But the Scarborough shoal standoff has shown that there’s no gain for both countries going to war over those unhabitable rocks.

Even if the overlapping territorial claims in the South China Sea is a core issue for China, it has more important concerns to attend to now than taking on a small country like the Philippines. Concerned about its international image, China does not want to be seen as a bully.

The Philippines, knowing that it cannot fight a military and economic giant China, needs to resort to other mechanisms to protect its territorial integrity.

Del Rosario raised again the idea of bringing the issue to the United Nations International Tribunal on the Law of the Sea, a conflict mechanism that China has ruled out preferring to deal with the issue bilaterally.

The Philippines continues to “study” that option fully aware that it’s an ace or resource more effective kept in reserve rather than used.